This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

St. Louis • A federal judge in Missouri on Tuesday granted a stay of execution to murderer Joseph Paul Franklin just hours before his scheduled death, citing concerns over the state's new execution method.

U.S. District Court Judge Nanette Laughrey ruled that a lawsuit filed by Franklin and 20 other death row inmates challenging Missouri's execution protocol must be resolved before he is put to death.

The state appealed Laughrey's ruling to the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis on Tuesday night, though it wasn't clear how quickly that court would rule. A second lower court federal judge, weighing a separate defense appeal contesting Franklin's competency to be executed based on his mental illness, also granted a stay and said the issue needs "a meaningful review."

Laughrey's 14-page ruling criticizes the timing of the state's changes to how it carries out capital punishment, specifically its plan to use for the first time a single drug, pentobarbital. It also takes issue with a plan to acquire the drug from a compounding pharmacy.

Laughrey wrote that the Missouri Department of Corrections "has not provided any information about the certification, inspection history, infraction history, or other aspects of the compounding pharmacy or of the person compounding the drug." She noted that the execution protocol, which has changed repeatedly, "has been a frustratingly moving target."

Franklin, who has been diagnosed as mentally ill, didn't seem to fully understand the stay, said Jennifer Herndon, his attorney.

"He was happy," she said. "I'm not really convinced that he totally understands that he was going to die."

Franklin, 63, was scheduled to die at 12:01 a.m. Wednesday for killing 42-year-old Gerald Gordon in a sniper attack outside a suburban St. Louis synagogue in 1977. It was one of as many as 20 killings committed by Franklin, who targeted blacks and Jews in a cross-country killing spree from 1977 to 1980.

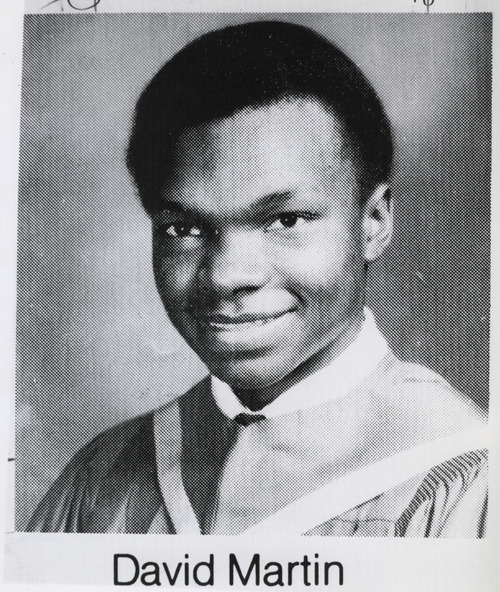

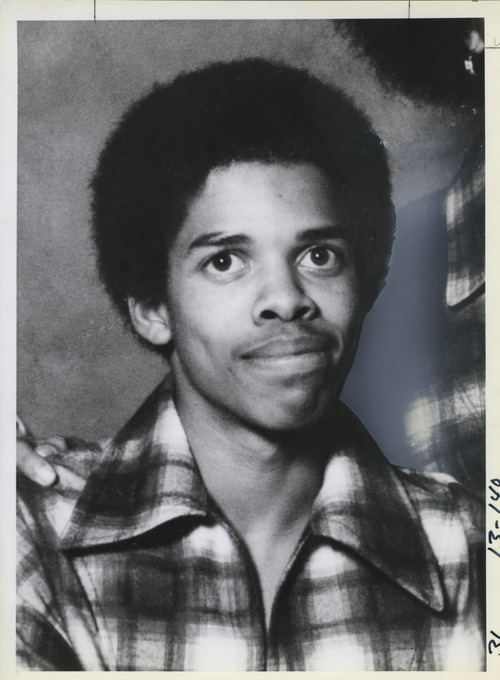

Among his victims were David Martin, 18, and Ted Fields, 20. Franklin gunned down the two black men as they were leaving Salt Lake City's Liberty Park with two white women on Aug. 20, 1980.

Karma Ingersol, one of the women with Martin and Fields when they died, said Tuesday she was devastated by the stay.

"His words are hurtful. He needs to be silenced, to be done away with," she said. "There's no closure for me. No closure and no forgiveness."

Terry Jackson-Mitchell, the pair's other companion, said: "I'm at peace no matter what happens."

Johnnie Mae Martin, David Martin's mother, opposes the death penalty.

She said Tuesday had been a day of sadness as she thought of Franklin awaiting execution.

"There is a time for everything and now wasn't the time. I don't know if he needs to apologize to more people or what but tonight wasn't his time," she said. "I just hope he'll be at peace."

Her daughter Denna Lightner responded to news of the stay with an "Amen."

Earlier Tuesday, she had asked for a letter to be delivered to Franklin expressing her forgiveness.

Lightner said the fact that Franklin had apologized and "come to know the Lord" in recent years allowed her to let go of anger over her brother's murder.

"I'm fine with whatever happens now," she said.

"My only hope it that all families connected to the slayings ... find comfort during this turbulent journey."

Like other states, Missouri long had used a three-drug execution method. Drugmakers stopped selling those drugs to prisons and corrections departments, so in April 2012 Missouri announced a new one-drug execution protocol using propofol. The state planned to use propofol for an execution last month.

But Gov. Jay Nixon ordered the Missouri Department of Corrections to come up with a new drug after an outcry from the medical profession over planned use of the popular anesthetic in an execution. Most propofol is made in Europe, and the European Union had threaten to limit exports of it.

The corrections department turned to pentobarbital made through a compounding pharmacy. Few details have been made public about the compounding pharmacy, because state law provides privacy for parties associated with executions.

"Throughout this litigation, the details of the execution protocol have been illusive at best," Laughrey wrote. "It is clear from the procedural history of this case that through no fault of his own, Franklin could not resolve his claims without a stay of his scheduled execution date."

She added: "Franklin has been afforded no time to research the risk of pain associated with the Department's new protocol, the quality of the pentobarbital provided, and the record of the source of the pentobarbital."

The stay pleased The American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri.

"Simply put, the state of Missouri is playing games by continually making last-minute changes to its protocol and hiding important information that the public needs to evaluate the execution plans," ACLU executive director Jeffrey A. Mittman said. "Treating the important constitutional issues at stake here, in such a cavalier manner, is a disservice to the people of Missouri."

It also pleased Franklin's daughter, Lori Gresham, who said she had spoken with her father earlier Tuesday but they had not talked about the execution.

She said she was "ecstatic."

"I'm so grateful," she said.

In a Nov. 13 Salt Lake Tribune interview, Franklin said he remained hopeful his sentence would be stayed and that he would have an opportunity to make amends to his victims and work to undo the bad "karma" he had created. "I would be really great to have that opportunity."

He described his own transformation during 33 years in prison as "a miracle."

"I've made an effort to try to change myself and become a better person," he said, mostly by studying world religions.

But in an interview with Fox 2 this week, reporter Tom O'Neal asked Franklin whether he deserved to die for his crimes.

Franklin paused and then said: "To tell you the truth, I actually think I do, yeah. I cannot say no to that question."

Tribune reporter Brooke Adams and correspondent Peg McEntee contributed to this story.