This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

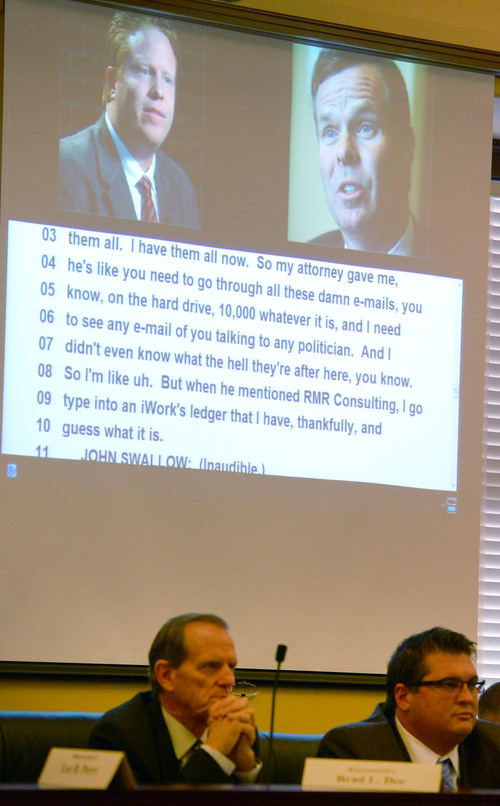

John Swallow left a 2012 meeting at Krispy Kreme with Jeremy Johnson so alarmed that he was in the cross hairs of federal investigators that Swallow took drastic measures to cover his tracks and ties to the indicted businessman, Utah House investigators said Thursday.

In the weeks that followed, Swallow obliterated his electronic footprints and created new documents designed to mislead anyone who might delve into his activities, according to evidence pieced together by a five-month investigation by a special House committee.

"We believe the evidence here shows Mr. Swallow panicked following the Krispy Kreme meeting, thinking about the consequences that would occur in terms of his political run for attorney general if Mr. Johnson went public with his allegations," said Steve Reich, special counsel to the committee. "And it was this panic that led him down a path of evidence elimination and evidence fabrication."

Within weeks of the doughnut shop exchange, Swallow had thehard drives on his state-issued computers wiped clean and appears to have purged thousands of emails, later lying to the public and investigators about their disappearance, Reich said. He bought a "burner" phone that couldn't be traced and created a fake paper trail for consulting work he did on a Nevada cement project.

"Based on the record available to us, our conclusion is that the Krispy Kreme meeting that Mr. Swallow had with Jeremy Johnson … set off a months-long spree where Mr. Swallow destroyed or lost records while creating new ones designed to support his version of events."

His record of behavior, his shifting story and attempts to mislead investigators and the public, taken as a whole, Reich said, cannot be innocently explained away.

"This is offensive," said Rep. Mike McKell, R-Spanish Fork, a member of the committee. " ... I think voters and the people of the state of Utah ought to be outraged by this."

Swallow's attorney, Rod Snow, suggested Reich was presenting information in a manner that justifies the price tag of the probe — approaching $3 million — and insisted documents weren't created or deleted to mislead or stymie investigators.

"I can see how and why Reich is connecting these dots, but I disagree with the way he is connecting the dots," Snow said. "There are innocent explanations that are just as plausible as those put forth by Reich. But the committee does not want to hear or believe that."

Neither Swallow, nor his GOP predecessor, former Attorney General Mark Shurtleff, agreed to be interviewed by House investigators.

Lawmakers cut short their probe after Swallow, a Republican, announced Nov. 21 he was resigning as attorney general, citing the financial strain of defending himself and saying he believed the GOP-led House probe was calculated to drive him from office.

Reich's account painted a damning picture of Swallow's actions after the meeting at the Orem doughnut shop.

The encounter's main topic was $250,000 that Johnson and his business partner, Scott Leavitt, had paid in 2010 to Swallow's former employer, Richard Rawle, the owner of the Provo-based Check City payday-loan chain, to help Johnson with a looming federal investigation into his business.

By the time of the April 30, 2012, meeting, Johnson had been indicted, accused of defrauding customers out of millions of dollars. He and Leavitt, who had put his house on the line to pay Rawle, wanted their money back.

During their exchange, Johnson alluded to the federal probe, and suggested Swallow, then a chief deputy attorney general, would be an attractive target. The St. George businessman warned Swallow that if he had received any of the money from the deal with Rawle, it would be hard to explain.

Swallow had, in fact, received part of the money Johnson paid — $23,500 that Swallow said he had received for consulting on a Nevada cement project. Swallow was clearly concerned about federal investigators.

"I think I'm their target," Swallow said.

In the weeks after the meeting, the House committee discovered, Swallow created invoices to justify payments he had received more than a year earlier from Rawle and made entries in his day planner meant to support the hours billed on the invoices.

However, Reich said, investigators were suspicious of the entries and, when the hours he billed Rawle for on the cement project were lined up with the time sheets for work in the attorney general's office, it showed that he was working 18 hours, 20 hours, even 24 hours in a given day.

Swallow didn't come clean about the backdated records until weeks of investigation produced evidence they were fabricated and investigators confronted Snow about the inconsistencies.

It was part of a pattern, Reich said, of constantly "shifting and, at times, contradictory" stories Swallow told to investigators to explain his actions that "go well beyond the normal frailties of human recollection."

Perhaps nowhere were the inconsistencies in Swallow's stories more glaring than in his explanation of data lost or deleted from, as Reich put it, every electronic device that Swallow used since he joined the attorney general's office in December 2009.

The attorney general office's computer technician said in a sworn statement that Swallow asked him in July 2012, weeks after the Krispy Kreme meeting, to wipe out all of the data on his state-issued desktop and laptop computers — claiming that the action was needed to protect private information related to his then-role as a Mormon bishop.

An external hard drive, backing up the data, was left on a plane and never recovered. He lost an iPad in Washington, D.C., and replaced a cellphone during summer 2012.

He also appears to have intentionally deleted all of his emails from 2010, Reich said. Swallow publicly argued that the emails were lost when the office migrated to a new email system. It wasn't true, House investigators concluded, and the messages were purged months earlier.

Swallow knew the messages were gone months before the state changed email systems, but never told investigators until he was confronted with evidence disproving his story.

Swallow's attorney asked for and received a copy of the computer tech's sworn statement the night before he announced his resignation, saying it could help with a decision that was being made.

Additionally, Reich said, computer experts spent considerable time and money trying to recover data from a hard drive in Swallow's home computer that had been replaced by the office's technology staff a few months earlier — a fact that neither Swallow nor Snow shared.

"This committee spent literally hundreds of thousands of dollars proving the 2010 email was not lost during the migration when quite obviously Mr. Swallow knew all along what the truth was, yet he never said anything about it to this committee until he was absolutely forced to," Reich said. "That's an example of what I mean when I say this committee's investigation has been obstructed."

Snow said it's wrong to blame Swallow for the cost of the probe.

"We do not believe that any delays cost the taxpayers any extra money. That is a nice ploy: Blame the cost on the person you are investigating who has already resigned."

During the Krispy Kreme meeting, Johnson advised Swallow to "go get a friggin' Wal-Mart phone," a prepaid device that would be difficult for law enforcement to monitor.

Swallow did just that.

According to testimony from campaign staffers, he directed an aide to buy a so-called "burner" phone days later.

"John needed me to make a purchase that could not come back to the campaign at all," staffer Seth Crossley wrote to the campaign's treasurer. "I paid cash."

Reich said others confirmed the purchase referred to was for Swallow's phone — an action that Reich said speaks to Swallow's state of mind after the meeting with Johnson and a "keen awareness" of the digital footprints he might leave for investigators.

Reich alleged Swallow obstructed the House inquiry and engaged in activity that other investigators — including a criminal probe being conducted by top prosecutors in Salt Lake and Davis counties — may want to consider.

"Let's assume John Swallow is the most technologically unlucky human being on the face of the Earth," Reich said. "Why didn't he just come forward at the beginning and tell this committee what happened? Why is it we had to drag every piece out? Why is it the story changed and morphed every time almost that we confronted him with our findings?

"The behavior that we've seen is not consistent with someone who believes they have an innocent explanation for what happened," he added. "It is consistent with someone who has hunkered down and made a judgment that the only way through is to wait and see what this committee came up with and then come up with an explanation that takes that into account."

Legislators were incredulous at the findings.

"There have… been times when the intentions of this committee and the resolution of our colleagues has been called into question," said Rep. Rebecca Chavez-Houck, D-Salt Lake City. "I'm just very offended that our integrity has been questioned in light of everything we have [heard]."

Reich previewed some of what the committee will hear Friday, expressing investigators' concern about a "daisy chain" of nonprofit entities established by Swallow's campaign consultant, designed to hide Swallow's political contributors — some of whom would be politically unpopular.

The Swallow political machine, Reich said, "violated the spirit and perhaps the letter of the law" by using the network of entities to stage attacks on Sean Reyes, whom Swallow bested in a Republican primary for attorney general last year, and former state Rep. Brad Daw, who was the target of attacks from Swallow's consultant, Jason Powers, in his 2012 campaign.

Reich also said there was a pattern of "pay-to-play" in which Swallow received gifts and benefits, personally or for his campaign, including using Johnson's spacious 75-foot Lake Powell houseboat on three separate occasions.

Rep. Lee Perry, R-Perry, said the findings were valuable — if frustrating.

"I'm really upset at how much money we have spent … because Mr. Swallow couldn't tell us the truth," he said. "I kind of expect it from somewhere back east or in Illinois, but I didn't expect it in Utah." —

Attempt at a cover-up?

Special counsel Steve Reich and House investigators alleged the following improper actions, among others, taken by former Attorney General John Swallow:

Fabricated evidence

• Created postdated invoices in 2012 for work Swallow supposedly did on a Nevada cement project in 2010 and 2011 for Check City owner Richard Rawle.

• Listed questionable entries, after the fact, in a time-management journal showing when and how many hours he worked for Rawle.

• Helped prepare a declaration Rawle signed three days before his death that Swallow later said Rawle's team had created.

Destroyed evidence

• Deleted emails from a personal account.

• Directed an attorney general's office computer tech to erase hard drives on his work computers and replace a hard drive on a home computer.

• Deleted electronic calendar items.