This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

First he lost his driver license.

As his vision worsened, Craig Maxfield Chappell could no longer easily watch TV reruns of "Hee Haw," recognize faces or cook meals without singeing his eyebrows. "I have to get right in there to see what's going on," the retired road construction worker and rancher said.

But when macular degeneration threatened to rob Chappell of cherished daily outings to tend his horses, the 86-year-old saddled up to be the first patient in Utah to have a pea-size telescope sutured in one of his eyes.

Surgeon Majid Moshirfar performed the surgery without complication the day after Christmas at the University of Utah's Moran Eye Center.

The device won't fully restore Chappell's sight and it could take two to four months of rehabilitation before he realizes any benefits, said Moshirfar, an ophthalmologist at Moran.

"But it should give him better vision at a distance and enable him to read again," said Moshirfar, who wishes he could offer the device to more patients.

"These patients are desperate for a solution. I have to turn away people because they're not good candidates," he said.

Medicine is an evolving science, and technologies like the telescope are just one solution among many being explored for blindness, said Moshirfar. "One day we'll be using genetic engineering to change the tissue of the macula ... to revive tissue rather than replacing or cutting it."

But for now, and possibly decades to come, implants are a viable solution to life-robbing vision loss, he said.

Macular degeneration is the leading cause of age-related blindness, affecting about 8 million people in the United States, according to the National Eye Institute.

But only a fraction of those diagnosed are candidates for the CentraSight telescope.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) conditionally approved it for patients age 75 and older. They must have end-stage (dry-eye) macular degeneration and be beyond the window for drug treatments.

The guidelines exclude patients who have had cataract surgery and warn that the device can damage the cornea.

"It's not a five-minute cataract procedure where patients can drive a car the next day," said Robert Cionni, medical director of the Eye Institute in Salt Lake and treasurer for the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery.

Medicare covers the device, which is priced at $15,000, not including the hospital's or surgeon's fees.

"It has to be done by a skilled surgeon ... but the benefits can be tremendous for a group of patients who don't have other options," Cionni said.

Previously for patients with disease as far advanced as Chappell's, the only solution was a magnifying glass or telescope affixed to eye glasses.

Placing the telescope inside the eye, said Moshirfar, affords greater mobility and gives patients a bigger field of view.

Macular degeneration damages the center of the retina, or macula, causing a loss of vision in the center of the eye.

When Chappell, who was diagnosed eight years ago, looks directly at someone, he can see shoulders but not the person's face.

"It's like a black hole. I can see peripherally and ride my four-wheeler to the field where I keep my horses by keeping an eye on the white line," said Chappell who owns farmland in Fremont, a remote area in south-central Utah.

"I can't see cars coming, but people around here realize I don't do too good and they watch out for me," the widower said.

The telescope, a miniature replica of the original Galilean version, works by magnifying what's in front of the patient by more than two times and projecting it back onto the parts of the retina that still work.

"It recruits the peripheral retina [for central vision]," Moshirfar explained.

This means Chappell will lose peripheral vision in the eye with the implant. But he'll retain it in his other eye, and ideally the two will work together to form more complete images.

Before the surgery Chappell (pronounced like chapel) underwent tests to see if he was a good fit, including looking through a simulator scope to show how the implant might improve his sight.

"I could read the eye chart as far as my son could with his natural eye," he said.

His surgery took just over an hour. Chappell was sedated but awake throughout.

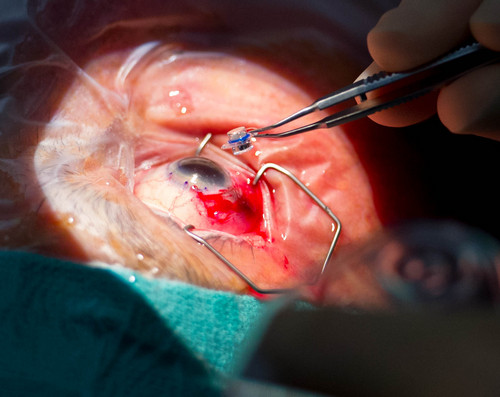

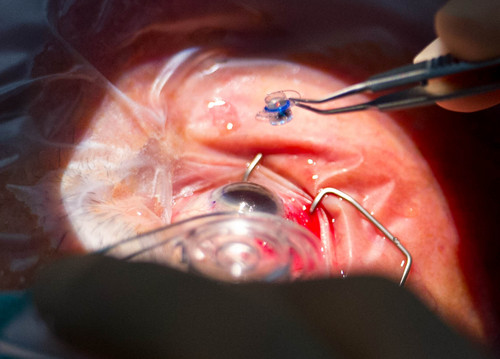

Flanked by colleagues eager to observe, Moshirfar began by peeling back a portion of the fibrous protective layer of the eye known as the sclera.

He made an incision at the edge of the iris and inserted a device to break up and suction out Chappell's clouded lens. Then he replaced the lens with the telescope, tucking it inside the pupil behind the muscular ring of the iris.

It took a few minutes to get the telescope positioned just right.

"Hang in there. We're almost done," he told Chappell. "The lens is in there. I just have to suture it with about nine to 10 stitches, OK?"

Chappell was able to return home that day. But he has months of therapy ahead of him to retrain his eyes and brain.

In a clinical trial of the telescope in 219 patients, 90 percent were able to see two more lines on an eye chart, and 75 percent moved from severe or profound impairment to moderate vision impairment, according to the FDA.

Chappell is optimistic but worries he'll forget to heed Moshirfar's warnings against rubbing his eye.

"I don't know if my brain will adjust to it or not," he said.

But the risks are worth the chance of being able to do things most people do without a second thought, he said.

"I'm pretty healthy. Everyone says I look good, but I can't see myself in the mirror," he joked. "But I'd be in better shape if I could do little things like see scores to the ball games on TV and or what I'm eating on my plate."

Twitter: @KStewart4Trib