This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Hawthorne Elementary Principal Marian Broadhead's voice crackles over the intercom with an afternoon announcement: The air quality has worsened since morning, she says, and students with asthma or colds should stay inside for recess.

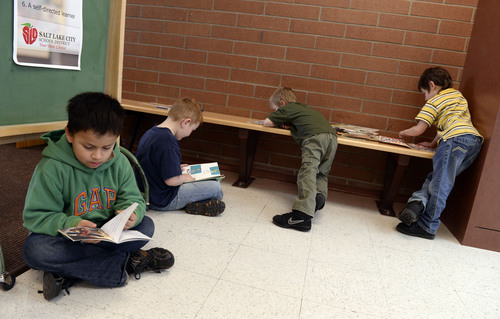

A bell sounds and nine children tumble to a bench in the hall outside Broadhead's office where they quietly read. Others stay in their classrooms and draw or play games.

Among those stuck inside: 9-year-old Soren Bell, who was recently diagnosed with asthma and shyly acknowledges he'd rather be playing "fire demons," a modified game of tag, with his friends.

Indoor-recess policies are a new phenomenon — a reminder for parents of the price their children are paying for modern fossil-fueled conveniences. It's disruptive for teachers who use that time to prepare lessons and an example of the health trade-offs all Wasatch Front residents make during those stagnant stretches of winter when toxic pollutants pool in the valley.

"It's disheartening. I'm the parent who says, 'When it's snowing, send them out' because exercise is so important for growing bodies and brains," said Soren's mother, Saralinda Bell.

Utah's decade-old recess guidelines were updated in 2008 and developed using data collected by measuring the indoor-air quality and lung capacity of students at Hawthorne and other schools.

They are a blunt instrument, say health experts, but the best they can be, given what's known about pollution's health harms.

"We know air pollution is bad for human health," said Robert Paine, a pulmonologist at the University of Utah who heads up an interdisciplinary center that funds air quality research.

But there are no data to define safe pollution thresholds, whether for a healthy adult, a young child or an ailing grandparent, he said.

Is 20 minutes of outdoor exercise safe, or none at all? What's the fallout from a lifetime of "moderate" exposure? And what about people living near a refinery or major roadway who are exposed all the time?

"We don't regulate or assess that," said Michelle Hofmann, a pediatrician and clean-air advocate who helped with the update of Utah's recess guidelines and has pushed for more air monitoring and better air filtration in public schools near highways and freeways.

"These are the kinds of conversations that are happening now," she said.

Even with a growing population and expanding transportation corridor, the Salt Lake Valley's air has improved since passage of the federal Clean Air Act in 1970. Future regulatory fixes will have to be more "prescriptive," said Hofmann.

But families living under the haze can't shake the feeling that it's getting worse — perhaps because our understanding of pollution's health perils has grown more expansive and alarming.

—

'We need to pay attention' • Saralinda Bell wonders if pollution could have triggered Soren's asthma. His attacks are generally brought on by seasonal allergies, said Bell, noting asthma runs in the family. "My mother has it," she said, "so maybe he's susceptible."

Jenne Parsons, the mother of two Hawthorne students, can't help but think exposure during her pregnancy may have something to do with her 14-year-old son's autism. "In my generation, only one member of my family is on the [autism] spectrum. But in the next generation there are four on the spectrum, including nieces and nephews."

Hawthorne's playground abuts 700 East, a heavily traveled, six-lane highway that at rush hour is backed up with idling cars and trucks. Scores of Utah schools are similarly situated along transportation corridors.

"It's like any other school where parents struggle to balance doing their part to improve air quality, such as walking or using the bus, with the reality of, 'How do I get my child to school on time?'" said Hawthorne parent Stephen Bloch, an attorney for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.

For Bloch's 10-year-old son, bad-air days bring occasional complaints of a scratchy throat, red eyes or a cold that lingers longer than usual. "But when January rolls around, you think, 'What am I doing in Salt Lake City? Am I taking days, months or years off my kids' lives?' " he said.

Paine, who directs the U.'s Program for Air Quality, Health and Society, would like to see researchers exploit Utah's hunger for local solutions and its natural, mountain-rimmed exposure chamber to answer some of these questions.

"We need to pay attention to the details of how pollution hurts human health," he said, "so that we reduce those health effects and protect those who are vulnerable."

Among them: children, because their lungs are still developing and they tend to be more active and spend more time outdoors.

—

'Pollution hurts our health' • Utah has been a major contributor to pollution-related health research, largely due to the efforts of Brigham Young University economist Arden Pope and his colleagues.

The first big eye-openers documenting pollution's impact on health date back to coal-burning days and "killer fogs" in Meuse Valley, Belgium (1930), Donora, Pa., (1948) and London, England (1952).

As deaths mounted and hospital emergency rooms filled up, these episodes proved pollution at very high levels, even for just a few days, can cause illness and death, said Pope. They motivated early clean-air legislation, which mitigated only the worst pollution.

Enter Pope, who moved from Texas to Utah for a faculty position at BYU in the late 1980s.

"I was teaching an environmental economics class shortly after Geneva Steel had shut down and reopened," he recalled.

The temporary closure of Geneva over a labor dispute made it the perfect test case, allowing Pope to document a dramatic drop in pediatric hospitalizations during that period.

During the next decade Pope, working with others, including researchers at Harvard, conducted a series of studies linking pollution to premature death, hospitalizations for respiratory problems and death from lung cancer and heart disease. He also documented reduced lung function in children.

Some industrial polluters disputed Pope's findings, which were used to set today's stricter national air standards. His research has since been replicated in hundreds of studies by scientists.

"We know pollution hurts our health, that it worsens symptoms of [existing] asthma and coronary artery disease," Paine said. "There's no question about that. I think the science is very, very clear."

But scientists are still testing the hypothesis that pollution can directly cause heart and lung disease. "Likely the answer is yes," Paine said, "but the data aren't there yet."

—

Tracing pollution's impacts • Some of the most provocative research on that front originated in Southern California in the late 1990s. Researchers there monitored thousands of school-age children in 12 communities, from fourth grade through high school, and showed stunted lung development in those exposed to higher levels of particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, acid vapor and elemental carbon.

They found days with higher ozone levels resulted in significantly higher school absences. And children who lived within a quarter of a mile of a freeway were 89 percent more likely to develop asthma.

Since then, preliminary studies have tied pollution to all manner of chronic ailments, from cancer and arthritis to depression and suicide. It has been associated with decreased movement in sperm in Salt Lake City, which has implications for couples trying to get pregnant.

Women exposed to high pollution during pregnancy have proved to be at greater risk of delivering a premature or low-weight baby, setting those infants up for health woes and developmental deficits.

A Harvard study showed women in a large national sample exposed to the highest levels of diesel exhaust and mercury were twice as likely to have a child with autism than those in the cleanest parts of the sample. These emerging findings are significant because they suggest pollution assaults the body on more fronts than previously thought.

The gunk in Utah's wintry air that worries health experts is PM2.5, tiny toxic particles or droplets less than 2.5 microns in diameter. These fine particles are dangerous because they may lodge deep in the lungs, causing them to become irritated and inflamed, said Benjamin Horne, director of cardiovascular genetic epidemiology at Intermountain Medical Center.

It's also likely that the body recognizes the particles as foreign, outside invaders, triggering an immune response and widespread inflammation, said Horne, who has produced research linking Utah's pollution spikes to increased hospitalizations for chest pain and heart failure in adults.

But fine particles and ultra-fine particles, less than 100 nanometers in diameter, are now thought to actually penetrate lung tissue and reach circulating cells and the brain. (A nanometer is one billionth of a meter).

There remains considerable debate about how this happens and what it means.

But researchers have discovered soot in the brains of dogs and children in polluted Mexico City and documented damage to their prefrontal cortex.

Pollution is now being implicated in neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and stroke. It may even hamper the development of babies' brains in utero.

"It needs further study, but I believe the risk to kids' cognition and development is real," said Jennifer Majersik, a neurologist at the U. and the mother of two boys at Hawthorne.

How applicable to Utah is the existing research — such as the studies based on ozone and traffic-related pollution in California or Mexico? That's an open question.

—

Balancing the risks • The shifting, sometimes conflicting, information on pollution can be paralyzing. Saralinda Bell monitors the air quality daily but knows parents who don't.

"This is all kind of new to us," she said one afternoon last week while checking Soren out of school for a fun timeout from indoor recess.

It's not often that all students are kept inside during recess. In 2007, a year on par with the record-high pollution spikes in 2013, there were four days when particulates rose above the triggering threshold of 90 micrograms per cubic meter of air, according to the Utah Department of Health. But there are plenty of days that rise above safe levels for "sensitive" kids such as Soren.

Kids, too, are keenly aware of the health threats.

A group at Hawthorne has spent part of the year learning about pollution and its health toll, which is a good thing, said Majersik.

It's the younger generation that will internalize conservation messages and drive change, she said. "Today it's shocking to see someone over-watering their lawn or throwing trash from a car. But if you ask my mom, who grew up in the '50s, she'll say, 'Nobody thought about stuff like that back then.' "

She appreciates air quality alerts so she and her family can take steps to protect their health, but says she tends not to be a worrier.

Hofmann, the pediatrician, advises patients to take heed of alerts but not let them rule their lives.

Her son has asthma and if he is needing to use his rescue inhaler, she may send a note to school asking educators to keep him inside, even on lower-pollution days. But if his asthma is well-controlled, she'll let him go outside for recess despite the air quality because, she said, "I want him to have a normal childhood. We must balance all sorts of risks every day."

Twitter: @KStewart4Trib —

About this series

This is the second in an occasional series of stories examining Utah's air quality through the monitoring station collecting data at Hawthorne Elementary School, 1675 S. 600 East in Salt Lake City, and the surrounding community.

The air at Hawthorne Elementary is much the same as the rest of Utah's urban valleys — but the school is the focus of some of the most crucial air monitoring research in the state. Read our previous story here. —

Air quality town hall

The Salt Lake Tribune's Jennifer Napier-Pearce will moderate a town-hall discussion on Utah's air quality challenges with a panel of experts at 7 p.m. Jan. 29 in the Salt Lake City Main Library, 210 E. 400 South. The discussion will be broadcast live on KCPW 88.3/105.3 FM and at sltrib.com. You can submit questions in advance by sending an email to utairquality@sltrib.com. Share the story of your bad-air day

For some Utahns, inversion season is simply annoying. It means fewer outdoor exercise days, eye and throat irritation and a less-than-picturesque view. For others, though, the cloud of pollution that clings to the valley floor is a serious threat that exacerbates existing health problems and makes Salt Lake City virtually unlivable in the winter months.

• How does poor air quality affect you? The Salt Lake Tribune and KUED Channel 7 want to hear your bad-air-day stories — whether written or video-recorded. Send stories to utairquality@sltrib.com with "My Bad Air Day" in the subject line or share them at facebook.com/saltlaketribune.

• Share video stories on Tout at tout.com/sltrib or at #mybadairday on Instagram. The Tribune and KUED will share your stories as part of our ongoing air-quality coverage. —

Poor air in America

The American Lung Association estimates that 127 million Americans, or 47 percent of the nation, live with pollution levels that at times are too dangerous to breathe.