This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Built in 1612, the Nagoya Castle was a layer cake of curling roofs topped with golden dolphins surrounded by one of the largest cities in Japan.

By the time Lennox Tierney got there, it was a pile of rubble.

"Nagoya took the worst destruction, almost, of any city in the world. More than Hiroshima," said Tierney. "Our bombers were given instructions they were not to take back any live bombs."

While those weren't atomic bombs, they had wreaked havoc on the city.

"It was total destruction. There was no way of knowing what street I was on, what part of the city, anything. I was literally steering by the North Star," he said. "I finally found myself next to a massive stone ... it was the base of what had been the castle."

Tierney went to Japan in 1947, serving as Arts and Monuments Commissioner in the U.S. Navy under Gen. Douglas MacArthur as part of the occupation government of Japan. He was tasked with tracking down, cataloging and saving what he could of the artistic and cultural history of Japan shattered by World War II.

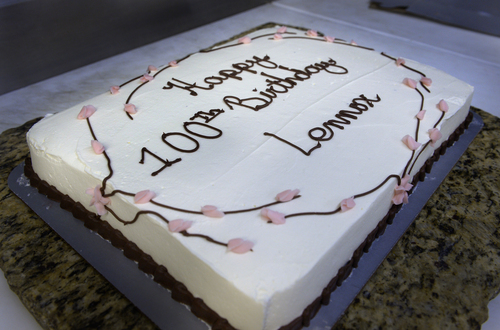

Tierney, who celebrated his 100th birthday last week , lived something similar to the forthcoming movie "Monuments Men," though much of his art-hunting happened half a world away from the European theater in the film.

His interest in Asia started at a young age, when his pharmacist father was sent to the Philippines by the military to look for medicinal plants after the Spanish-American War. The Japanese influence in craftsman design magazines his mother loved sealed the deal, and when he entered college at UCLA he self-created a major in Asian art.

After graduation, Tierney started teaching a military technical-training course in Beverly Hills — until the day when an admiral asked him to leave on a mission in 48 hours.

"I said, 'Of course not. I couldn't possibly do that,' " Tierney said. He said, 'Well, it happens to be important.' "

After some negotiating, he shipped out for training within two weeks.

"My family all came to see me off and no one knew where I was going," he said. He ended up flying to Salt Lake City and was driven to Boulder, Colo., when he started "22 months of hell. Physical, mental, the whole works."

In a recent interview, he remembered Japanese language teachers placing a foot between their students' feet to nudge them awake when they dropped off. Tierney was 24 when his training ended.

On a visit home before he was shipped off, he went to a going-away party for a woman named Catherine Peha, who was also headed to Japan.

"It was love at first sight," Tierney said. Her Jewish family had been driven from Spain in the 17th century to an island in the Mediterranean Sea before they ended up in California.

"I made a mental note once I got to Japan to look her up," he said, but he didn't initially have much luck. "She was busy all the time!"

He was also working hard in Japan, with duties that ranged from supervising a team charged with purging propaganda from children's textbooks to advising the unschooled MacArthur on Japanese culture. He found an eager reception from the Japanese.

"They were just hoping for a friendly voice in the occupation government," he said, someone who would speak up to preserve Japan's history and heritage.

And that didn't only mean paintings or sculpture. Gardens are a distinct and historic art form in Japan, one that Tierney explored and cataloged during his time there. As he visited gardens, he started seeing a mysterious, ghostly figure wearing a black overcoat seemingly dogging his steps.

It turned out to be Issuu Noguchi, "the greatest Japanese-American sculptor," he said. He teamed up with the artist and they started traveling the country together.

Tierney was able to save some important works, such as a sculpture of a monk with a bronze wire coming out of his mouth mounted with tiny Buddhas.

"He's preaching the doctrine," said Tierney. "It's the only sculptural work that makes sound visible."

It was housed in the Rokuharamitsuji Temple outside of Kyoto that had been damaged in the war, but before the destruction, people hid it away in a safe place. It was brought out again during Tierney's administration.

It was one of thousands of pieces he preserved, returning the art to its owners when he could find them and bringing the pieces to the national museum when he couldn't.

Other works, though, were lost forever in the war. In Toyko, Tierney met a tea master who had one of the country's largest collections of netsuke — tiny, intricate sculptures Japanese men used to store and carry vitamins and other small items.

"We made a mistake in the West. We thought all sculpture came out of the Italian renaissance — big," he said. "I discovered the great sculptures of Japan were these little netsuke."

Along with the netsuke, the tea master had also amassed a collection of paintings and other sculptures. When "the war clouds began to gather," Tierney said, the man picked an out-of-the-way farmhouse to stash his art away from the presumable target of Tokyo.

But the spot turned out to be in the center of the destruction.

"It was on the path into Nagoya," Tierney said. "His total collection was destroyed. The greatest collection in Japan."

Tierney's tour of duty in Japan ended in 1952, and he was sent to Germany, where he tracked down Picassos scattered by Nazis. His reception from the locals, though, wasn't nearly as warm.

"I never felt unsafe in Japan," he said, but he didn't go walking alone during his three years in Germany. "A lot of Germans were bitter about the war and didn't accept [defeat.]"

And Tierney never gave up on Catherine. She finally found time for him, and the couple wed, returned to California and had a son together. Shortly after his return, he was approached by a "tall blond man" after a lecture he gave on Japanese culture who turned out to be the dean of the College of Fine Arts at the University of Utah.

Tierney has called Salt Lake City home for 40 years, visiting Japan with Catherine every seven years until her death from Alzheimer's disease. In 2007, the Japanese government awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun.

As a young man helping to rebuild the country, "I was seeing the works of art I had studied as great works ... in many respects, I felt I'd died and gone to heaven," he said. "It was a very amazing kind of experience."

Twitter: @lwhitehurst