This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Fourth-graders with a range of disabilities, each toting an iPad, vie for teacher Ana Park's attention at Newman Elementary in northwest Salt Lake City.

"What do I do next?" "Can I show mine?" they clamor on their second day with the iPads, which are being distributed in every classroom at the 480-student school this winter.

Newman is one of 10 schools chosen to join Utah's Smart School Technology Project; three of them are in the second year of having an iPad for every student.

The project, funded with $5.4 million set aside during the past two legislative sessions, is a big deal in these 10 schools, but it looks downright puny against the massive digital infusion envisioned by House Speaker Becky Lockhart.

The Provo Republican is proposing that Utah spend $200 million to $300 million to buy digital devices for Utah's 612,500 students, to train educators and to build the infrastructure in schools.

The Utah Board of Education is asking for a more modest $50 million, which before Lockhart announced her idea on Jan. 30, appeared pie-in-the-sky.

Both proposals, coming at time when Utah is more flush with cash than in recent years, reflect a national push to better prepare students for a digital world.

Only one state so far, Maine, has one-device-per-student statewide, which is Lockhart's goal. (Idaho voters rejected a statewide one-to-one plan after the state Legislature approved $180 million in funding).

In the rush to adopt technology, many states, districts and schools have made missteps, believing devices alone — without teacher buy-in or preparation — can make a difference.

"It's a mixed bag," says Howard Pitler, program director for McREL, a Denver-based research and development nonprofit, and co-author of a book for teachers on how to use technology.

There are no good data that look across a spectrum of schools to see if, overall, technology in the classroom is worth the cost.

"I can point to shining examples of transformative learning," says Pitler. "And I can point to other examples where nothing has happened other than spending a lot of money."

—

'The million-dollar question' • At Newman Elementary, Principal John Erlacher is eager to finish distributing the iPads, funded with $373,550 from the state and a matching amount from the Salt Lake City School District.

"If technology will help kids learn quicker and in a deeper sense," says Erlacher, "I'm all for it."

In Park's resource class, fourth-graders use Educreations software to draw out multiplication problems on their iPads. They record how they arrive at their answers, and share the recordings with classmates on a projector.

"The more they can visualize it," says Park, "the more cemented it becomes."

Teachers at Newman spent two Saturdays in the fall learning to use the iPads in school, and, for the first year, they'll have both an IT person and a "coach" to help them in their classrooms.

Erlacher's goal is for teachers to get comfortable using the devices this year and more creative next year. It will be a couple of years before he knows the project's success.

"Is it just a gadget or has it improved our language arts, math and science scores? Has it made our teachers better teachers?" he asks. "That will be the million-dollar question."

—

'Not a cheap proposition' • Rick Gaisford, the educational-technology specialist at the Utah Office of Education, says the state's schools last fall had one device — a desktop computer, or a laptop, tablet, iPod, etc. — for every three students. About a quarter of Utah schools have one device per student.

Some districts have worked to acquire one device for every student, at least in the middle-to-upper grades, including Park City, Wasatch, North Summit, South Summit, Piute and Wayne.

But even so, says Gaisford, it would take some 600,000 new devices to reach one-to-one statewide because the devices don't last long and many of the existing ones — such as 67 percent of desktops (think computer labs and teachers' desks) — are at least three years old.

He estimates it would cost $50 million per year to keep even a low-cost device such as a Chromebook, estimating a three-year life cycle, in every Utah public school student's hands.

"It's not a cheap proposition," says Gaisford.

And the devices are only part of it.

While the Utah Education Network's pipeline of broadband, delivered to every school, is the envy of states everywhere, 80 percent of Utah schools say they need infrastructure upgrades. "It's that last mile inside the building," Gaisford says.

It takes a lot of bandwidth for 400 or 1,000 or 1,500 students to download videos or do simulations at the same time. That infrastructure, Gaisford estimates, would cost $43 million.

A plan the Utah Board of Education developed in 2012 spells out three key pieces to putting technology in schools: the gadgets and the wireless system they run on; teacher preparation; and technical support to keep all of it running.

"It's not like we don't have a road map," he said.

—

Engaged, but with what? • Utah schools, like others nationally, have had mixed results.

Kearns High School put an iPod Touch into the pockets of 1,700 students for three school years, the first two years funded with a $1 million federal stimulus grant.

The biggest gains came in the first year, 2010-11, but they were incremental. And they weren't there in the second year.

The school had 3 percent fewer dropouts and a 3 percent improvement in the first end-of-year tests in language arts (English). Math scores showed no improvement — and continue to lag, which was a big reason the school got an "F" grade from the state last fall.

Jenny Peirce, the library's media and technology specialist, says the positives for the school far outweighed the negatives.

Seniors Jacob Metcalf and Tanner Westenskow agree.

Westenskow says he liked looking things up when questions popped up, such as in history class when he wondered about earlier times. Tanner says he often used flash card apps for history and English.

Even so, teachers voted to not pursue more funding to continue with the iPods, and the remaining devices were put in classrooms where some teachers continue to use them with students, says Principal Maile Loo.

Even with filters, it became a management nightmare for some teachers to ensure their students were using the iPods for academics.

"The kids would be engaged," says Loo, "but the teacher didn't know what they were engaged with."

—

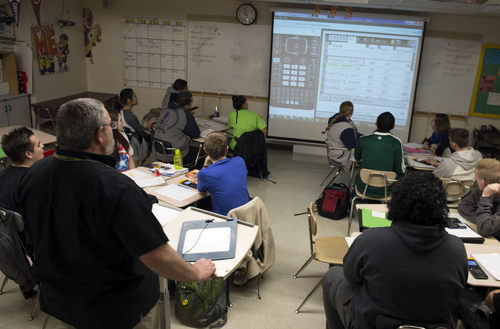

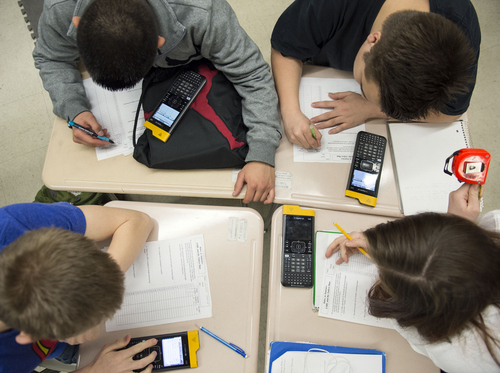

'I can tell...who is on task' • Nonetheless, many Kearns High teachers liked the tool, including Rob Lake, who still uses the iPods when he wants his math students to go on the Internet.

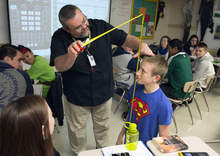

Technology includes more than computers, though.

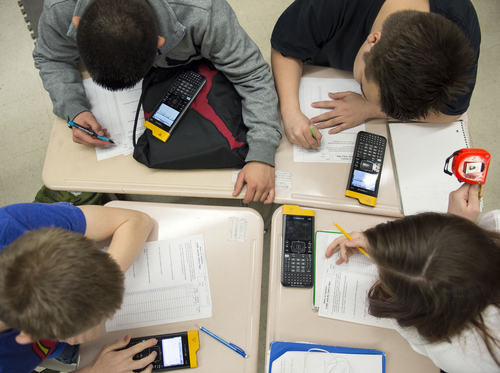

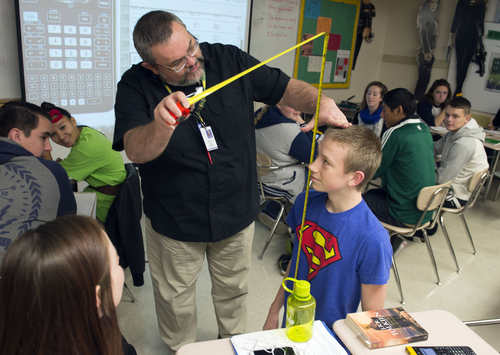

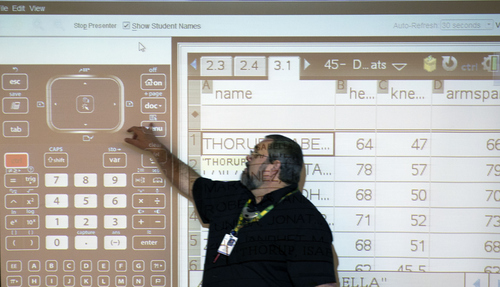

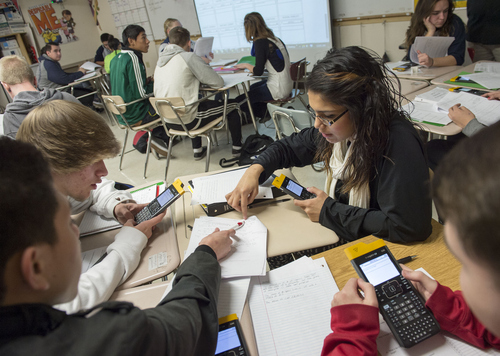

In an introductory statistics class last week, Lake had his students use tape measures to learn fellow students' height standing and kneeling. They then entered the data into TI-Nspire calculators that communicate wirelessly with his computer. He can "push out" a question that the students have to answer.

He had teams of students make scatter graphs with their data, and the graphs showed on a big screen.

That system cost $14,000 for Lake's classroom, which the school's Community Council funded with trust land money. Two more math teachers got the calculators this year.

Lake loves that he no longer has to rely on a gut feeling to know who is paying attention or who doesn't get a concept.

"It makes it really hard to not participate … and they know I can find them out. I can tell exactly who is on task."

—

Mixed results • It's still early days for Utah's 10 Smart Schools, but results were mixed in the first year that every student was given an iPad at Gunnison Valley Elementary, Dixon Middle School in Provo and North Sevier High in Salina.

Gunnison's third- and fourth- graders were less proficient in language arts and math in 2013 than in 2012, according to end-of-year tests. Fifth-graders saw improvements in language arts and science, but not in math.

At Dixon, seventh-graders improved in language arts and science, but eighth-graders didn't. Math scores dipped slightly for seventh-graders and dramatically for eighth-graders, but that's likely due to the rigor of the new Utah Core Curriculum.

At North Sevier High, the gains were small, but across the board in subject areas and grades. End-of-year science scores rose the most.

Gaisford, at the state education office, says it's not uncommon for scores to dip after a change. "It will be more interesting to see what happens this year."

Pitler, the Denver author and former principal, says educators and policymakers should not expect immediate gains in test scores.

That's because standardized tests in the United States do not ask questions that measure what technology prepares kids to be: creative, resourceful, persistent.

Technology used well can engage students and help them want to learn, he says, but that shows up on test scores only in the long run.

—

'It's going to pay off' • Wayne School District Superintendent Burke Torgerson in Bicknell agrees it's too soon to know whether his district's one-to-one initiative is paying off.

Nearly every student in the district now has a personal iPad (a handful of Hanksville students are still sharing). The elementary kids leave the iPads at school; older kids take them home and seniors get to keep them when they graduate.

A middle school teacher and that school's Community Council kick-started the program, Torgerson says. The superintendent says he's learned two key things: "You've got to have a lot of (technical) backing behind the scenes and infrastructure to do that."

And helping teachers learn to use technology is paramount. "We're looking at backing up and beefing that up more," says Torgerson.

He doesn't want gadgets to simply replace paper and pen, as would be the case if all a student did was use a computer to write an essay.

"What we have to start doing now," says Torgerson, "is providing real-world, task-oriented learning experiences."

He sees the students as doing most of the work, and teachers coaching and supporting them along the way.

"I think," he says, "It's going to pay off."

Twitter: @Kristen Moulton —

Who has the tech?

Ten schools have received Smart School Technology Project grants, which the Utah Legislature funded during the past two years for a total of $5.4 million.

iSchool Campus, a Park City-based business, was given the contract to run the project. Southern Utah University's College of Education and Human Development is evaluating it.

Three schools were funded beginning in the 2012-2013 school year, receiving 100 percent of the money it took to give every student an iPad and teachers both iPads and laptops for three years. Those are:

Gunnison Valley Elementary (Gunnison), 450 students, $813,600.

Dixon Middle School (Provo), 900 students, $1.6 million.

North Sevier High School (Salina), 243 students, $439,344.

Seven more schools were chosen last year, and awarded grants that the schools have to match over three years. Those are:

Utah Career Path High School (Kaysville), 175 students, $130,393.

Myton Elementary (Myton), 164 students, $122,196.

Freedom Preparatory Academy (Provo), 285 students, $212,354.

Beehive Academy (Sandy), 316 students, $235,452.

Pinnacle Canyon Academy (Price), 326 students, $242,903.

North Davis Junior High (Clearfield), 1,033 students, $769,688.

Newman Elementary (Salt Lake City), 500 students, $372,550.

Source: SmartSchool Technology Program Report 2013