This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Monument Valley • Music teacher Jeremy Johnson instructs his piano students on proper concert etiquette as they listen to a classmate play a tune from the musical "Cats."

Lean forward. Listen attentively. Applaud, he says.

"Even if you are totally bored out of your head, sit up in your seat," Johnson says, perched on the edge of his own as students take turns practicing in the auditorium for an upcoming recital.

Hours later, Johnson is with another group of students who stay after school once a week to learn to play the elegantly simple, carved native flute. They work with a prominent Navajo musician, Vince Redhouse, via Skype from his home in Seattle.

From common courtesies to indigenous instruments, Monument Valley High School in southeastern Utah's San Juan District has a broad mission.

The school, which has grades seven-12, must prepare its 216 students, who grow up amid the Navajo Nation's iconic red mesas, for success in the wider world: jobs, college, trade school, Anglo culture.

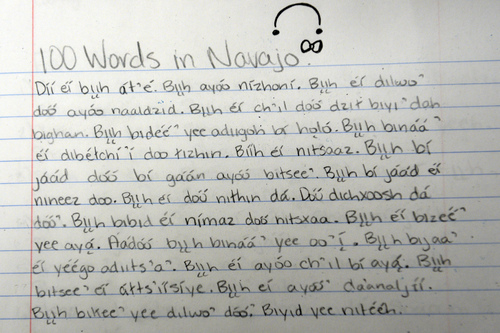

But it also must teach the Navajo language and traditions as a result of federal lawsuits, beginning in the 1970s, that accused the district of unequal treatment of American-Indian students.

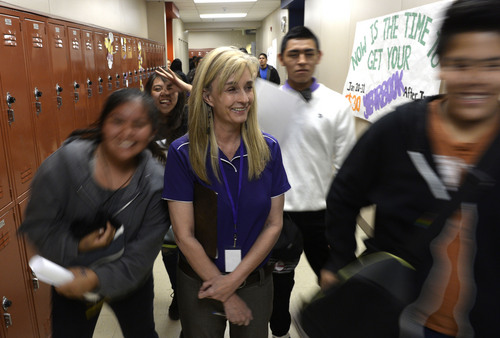

The challenge for Sylvia McMillan, hired this school year to be the struggling high school's "transformational principal," is to hew close to the second mission while dramatically improving performance of the first.

"We can view them as competing," says McMillan, whose appointment still rankles many parents. "But we don't want to. We want the best of all worlds for these kids."

—

From 'F' to fresh start • Monument Valley High, according to Utah's new School Grades accountability system, is a failure.

It was slapped with an "F" grade in the fall, joining Kearns High as the only two traditional high schools in the bottom 15. (The others were an online school and alternative high schools, which serve at-risk students.)

Monument Valley's elementary, Tse'bii'nidzisgai School, also got an F, scoring dead last among 555 grade schools in the state.

The grades are based on student achievement in math, language arts and science, as well as graduation rates — measures by which American Indians lag across the nation.

Frustrated by years of small gains that could not keep Monument Valley High on pace with academic improvement elsewhere in Utah, the San Juan District school board took a dramatic step.

It adopted what federal education officials call a "transformational model" to try to fix the school's problems, which meant replacing the beloved principal of three decades and half the school's 16 teachers.

The move angered parents, who also were stung by the suggestion that their children were academically inferior.

Racial tension is always just below the surface here, where county and school government is seen as dominated by minority whites. American Indians comprise 52 percent of San Juan County's population.

The shake-up exposed old wounds, including grievances behind lawsuits that forced the San Juan District, based in Blanding, to build Monument Valley and other Navajo Reservation schools beginning in the 1980s.

But it also gave the school a fresh start, says Superintendent Douglas E. Wright.

It put Monument Valley High in the running for Title I School Improvement Grants, which could mean $600,000 to $800,000 for the school during the next three years. And it will send district and school administrators this spring and summer to a boot camp: The Partnership for Leaders in Education at the University of Virginia.

The school had a climate that was too comfortable with mediocre achievement, says Wright. "We want to see dramatic differences in performance."

Nelson Yellowman, a school board member from Monument Valley, says, "We can do better. Why not us?"

—

Amid the monuments • Monument Valley High students grow up in a world that is both beautiful and harsh.

They live in trailers, modest stucco homes and hogans spread across nearly 30 square miles, passing daily by mesas and buttes known the world over from the many movies — including 2013's "The Lone Ranger" starring Johnny Depp — filmed here.

Ninth-grader VanteJren Atene sometimes rides his horse to school from his home near Oljato Wash, 10 miles to the northwest. On a day in late January, a windstorm made his ride home, with girlfriend McKalette Clark and buddy Jaydon Yazzie, a gritty, grinding one.

The school has a corral and provides hay and water.

Seventh-grader Kody Smith lives in the backcountry, past where visitors to the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park are allowed to go.

His mother, Lorraine Stanley, who runs the computer lab at the elementary school, drives Kody and his younger sisters to school each day on rocky and rutted roads that occasionally cross sand washes.

They live just 17 miles from the schools, but it takes an hour each way in her Jeep.

The family lives in a partially finished home that Kody's father, Meryl Smith, is building as money allows. They have no indoor plumbing and their only electricity comes from a gasoline-fueled generator or a small solar panel, which power the few lights and, sometimes, the television. An oil barrel converted into a wood stove warms the house. A cooler on the concrete slab floor keeps milk cold.

The Smiths haul hundreds of gallons of water and spend roughly $20 each week at the Goulding's Laundromat near the schools.

But Stanley says life here, with views stretching to the Blue Mountains near Monticello on the north and to the hogan where she grew up on the south, is good for her children. One can see wild mustangs in the distance; goats and sheep graze until it's time to seek refuge from coyotes in pens at night.

Kody, Karlicia, 9, and Keilana, 7, have daily chores that include feeding the sheep, goats and dogs, and bringing in wood. Those teach them responsibility, and "they're more adult" than cousins or friends, says their mother.

—

A remote challenge • The family's lifestyle is not unusual in this part of Utah. Nearly a third of Monument Valley High's students have no electricity and/or no indoor plumbing at home.

Their families raise sheep and goats for wool and meat. They make money catering to tourists at the handful of motels and restaurants, cashiering at Goulding's trading post and other stores, weaving baskets or guiding horseback trips among the monuments.

The school is one of the most remote in the nation, which locals jokingly measure by the time it takes to drive to the nearest Wal-Mart. Page, Ariz., is nearly two hours away; Cortez, Colo., is slightly farther.

All but three of the school's 216 students are Navajo, at least in part, and most are connected with teachers and classmates by an intricate clan system, even as 50 percent of them are technically "homeless," living with an aunt, an uncle, a grandparent or a friend.

Parents who can't make a living on the reservation are often gone for long stretches working out of state, perhaps on a welding job in Texas or at a California construction site.

More than half in this Title I school fall below the federal poverty level, qualifying for free and reduced price breakfasts and lunches.

Some, like senior Remington Begay, are immersed in American-Indian culture. His father is Comanche; his mother is Navajo.

He wears his hair in a long braid, an arrowhead necklace around his neck and a wide silver bow-guard that belonged to his grandfather on his wrist.

Outside school, Begay breaks horses for a trail-ride business and leads customers on horseback tours, sometimes stopping in a cave to improvise melodies on his flute, the haunting notes echoing off the walls.

On weekends, Begay says, he joins in Native American Church ceremonies in tepees or hogans, where peyote is shared.

Other students are less anchored in the Navajo culture.

Though hundreds of miles from the nearest city, Monument Valley's students have many of the same problems as their urban peers: alcohol and drug abuse, teenage pregnancy.

"It's like an inner-city school," McMillan says, "but we're in the middle of nowhere."

—

Supporting success • McMillan reaches for a book that sums up her task at Monument Valley: "Driven by Data, A Practical Guide to Improve Instruction."

"This is where public education is going," says the new principal. "And it doesn't work here."

She has worked in India and Africa as well as in private schools in northern Utah and California. She has a doctorate in education from Brigham Young University.

By focusing on data, "I worry that we are stifling creativity in the kids," says McMillan, who, like her new art and music teachers, is in awe of many students' talents.

"There are brilliant students here. Brilliant!" says art teacher Josh Boehner.

Nonetheless, McMillan and her teachers are pushing hard for quantifiable gains, particularly in the core classes.

The early results are encouraging, she says, especially in language arts. Students earned 70 F's in all classes the first term, but only 40 the second.

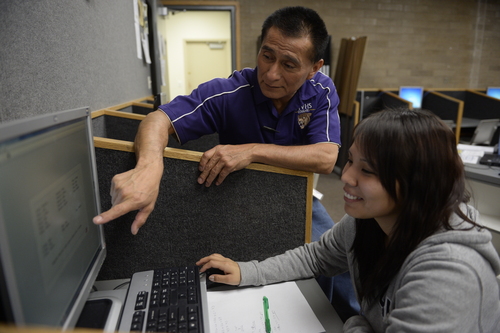

One of the key new programs is Guaranteed Personal Success, GPS for short.

A computer spits out a list of students who are missing assignments at the end of every school day, and those students must go to the cafeteria for an hour after school to catch up.

Ninth-grader Josiah Nelson says he used to slough off in school and often skipped it altogether. (The school has a high 8 percent absentee rate).

But GPS changed that; he missed wrestling practice when he had missing assignments, so he stays caught up now.

"I wasn't used to doing that much work in one day," he says.

McMillan says the number of students routinely in GPS after school has dropped from 150 to about 40.

Christiana Tsosie, a ninth-grader, says GPS helped her learn to plan her time better. But she acknowledges students are feeling the heat. "It's putting a lot of pressure on kids now."

—

Pulling in parents • The school is the community's gathering place.

When Lucasfilm Ltd. dubbed the "Star Wars" saga's "Episode IV: A New Hope" into the Navajo language last year, it had a screening in the high school's auditorium.

The stands overflow at football and basketball games.

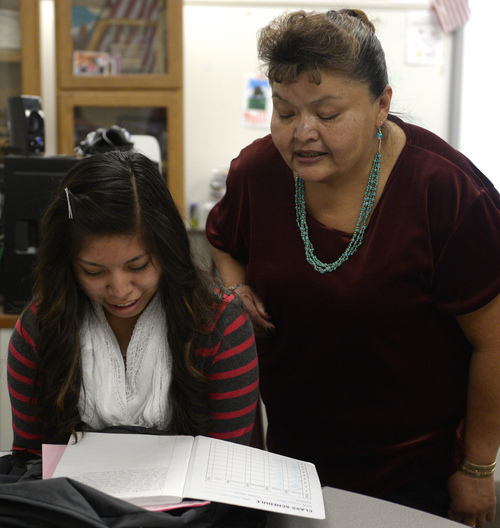

But most of the students' parents do not get involved in the educational side of school, says Community Council President Christine Rock. "We really need to push that," she says.

Educators routinely urge parents to read with their children at home, but Navajo culture doesn't have such a tradition. The Dine' language is oral and was not written down until Anglos, for the most part, forced the issue in the past century.

Books are not really part of most families' lives, says Vanessa Russell, the school's reading teacher, a 2001 graduate of Monument Valley who earned a bachelor's degree at Southern Utah University.

Many Navajo parents are not accustomed to being involved with their children's education, Wright says. "There's a bit of mistrust because of their educational experiences."

Many were bused long distances or sent away to Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools, so their own parents rarely visited their schools.

"There's a mentality that what happens at school is for education and what happens at home is different," Wright says. "I keep thinking we're going to be in a generation that is going to overcome that, and we are, bit by bit."

—

Too soon to tell • Parent Watson Clark says the new GPS program has helped his son stay on top of schoolwork. Otherwise, though, Clark is wary of the reforms and critical of the district's turnaround plan.

Clark and his wife, McKinlena Smallcanyon, were volunteering at the school on a recent day, packing and spraying sand on the outer wall of the school's hogan.

He's still smarting over his son's recent in-school suspension.

Clark says his son was punished for speaking his native tongue; McMillan says he was punished for cursing — albeit in Navajo — and for refusing to go to her office.

"She hardly knows anything about the traditional culture of the Navajo," says Clark.

Jack Seltzer, the husband of former Principal Pat Seltzer, taught agriculture classes, raising sheep and overseeing a traditional garden at the school to help fund its programs.

The couple, who have now moved from the area, were so much a part of the community that The View, a restaurant overlooking the tribal park, has a dish named for him: the Jack Seltzer Green Chile Quesadilla, right alongside The John Wayne burger on the menu.

"We're wishing for the school board to get us a person who knows Navajo or the history here," says Clark.

Larry Holiday, who carries letters from the school to the far-flung students' homes as the school's liaison, says that sentiment is common. It's too early to tell if the reforms will work, he says.

Tonie Dee is a longtime teacher who at times saw her own classmates punished for speaking Navajo at an all-English Indian Affairs boarding school.

She says the community is still suffering shock over the loss of teachers and, particularly, the Seltzers. "They were like pillars of the community, very, very giving."

Teachers, too, are feeling the pressure. "I've never had to work this much," says Dee, who routinely puts in 10-hour days as the school's family consumer science teacher and adviser to the student council and other groups.

The school's atmosphere needs to change, she says, but she fears the community is too unsettled to look to the future.

"The parents have to see where this is all leading," she says. "It's going to take a couple years."

Twitter: @KristenMoulton —

Grading Utah schools on the Navajo Reservation

The five Utah schools on the Navajo Reservation did not fare well in the first round of School Grades, an accountability program created by last year's Legislature.

The elementary and high school (grades seven-12) in Monument Valley both got F's, and the elementary and high school (grades seven-12) in Montezuma Creek got D's. Navajo Mountain High, with just 34 students in grades nine-12, was too small for a grade to be statistically meaningful.

Superintendent Douglas E. Wright says poverty and geography play roles in the schools' poor performances, mirroring a national trend for Indian schools.

Navajo Mountain, in particular, is difficult for district staff to visit. It is 200 miles, including some on dirt roads, from the district office in Blanding, a round trip that takes more than seven hours. —

Looking back: Schools have roots in lawsuits

The San Juan School District's schools on the Navajo Reservation have roots in lawsuits that alleged discrimination against American Indians in Utah's largest county.

Fifty-five percent of the district's 3,064 students are Indians, mostly Navajo.

A 1975 consent decree in the first case ordered construction of Monument Valley High near Oljato and Whitehorse High in Montezuma Creek, as well as bilingual education and renovation at two elementary schools just off the reservation but serving Indian students.

The lawsuit was renewed and splintered into several others in the early 1990s, resulting in settlements in which the district agreed to build Navajo Mountain High. Those named in the lawsuit also agreed to find funds to build an elementary school in Monument Valley. That school, Tse'bii'nidzisgai, opened in 2011.