This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The University of Utah's Moran Eye Center announced plans Thursday to enter into a uniquely close relationship with a multinational pharmaceutical company to develop a new drug to treat a leading cause of age-related blindness.

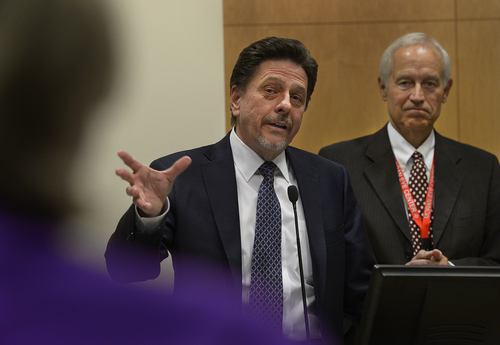

The partnership will bring "a very sizable amount" of new research money to Moran, said the center's CEO Randall Olson. Though he refused to say how much money the center will get from California-based Allergan Inc., he said the concept of working more closely with industry at an earlier stage in the research process could be a "historic breakthrough."

"I don't think there's anything quite like this anywhere in academia, where the two are teamed together where they're literally seamless," Olson said. Private money in university research isn't new and the U. already brings in more than average, but pharmaceutical companies are typically involved after a product has already been developed, during the clinical trial stage.

Olson said the traditional process of going from a scientific discovery to a treatment for patients is too slow, and decades of erosion in federal investment for research means scientists can't do as much important research, a situation he called a crisis.

"Much of the system in trying to take revolutionary breakthroughs in science all the way through the pathway out to clinical care was a very disjointed, dysfunctional process," Olson said. "Not only did it take an inordinate amount of time and an enormous of waste of resources. but many great ideas that really could have helped never make it."

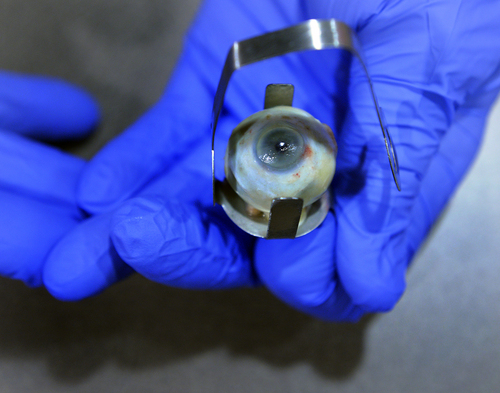

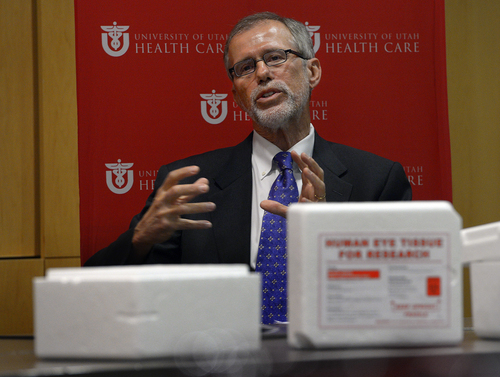

Allergan scientists will also work closely with Moran researchers during the 5-year partnership, and the company will get access to a vast repository of donated eye tissue collected by preeminent researcher Gregory Hageman, as well as the treasure trove of genetic data in the Utah Population Database.

Both will be useful in the development of a drug to treat age-related macular degeneration caused by genetic mutations.

"The day will come quickly where we've identified some very meaningful targets for this disease, and then we can hand it off to [Allergan] and they can do the magic that they do to make this all work," said Hageman, executive director of the Moran Center for Translational Medicine. "We will shorten the runway by years with this particular approach."

Hageman spearheaded the partnership with Allergan, a $29 billion company that makes everything from Refresh eye drops to Botox.

"They have access to resources we can't even dream of," Olson said, like the ability pay for genomics testing on the Moran eye tissue.

As to whether the partnership could raise conflict-of-interest issues, Olson said the scientists will be "100 percent ethical" and assessed by other professors at the U. Hageman, for example, wouldn't be involved in deciding whether a patient would be involved in a clinical trial.

But Olson also cast conflicts as an inevitable part of the process.

"If we don't have a lot of conflicts occurring ... we're not doing anything important," Olson said. "There's no other way."

The university and the company have already worked through years of negotiations on who will own the intellectual property and how to publish results, Olson said.

Future patents created together would be jointly held by the university and the company.

"If it's in the collaboration, it's pre-licensed ... including the royalties," Olson said. "There's nothing to slow it up."

The university will get money from Allergan upfront, as well as at certain milestones and future royalties.

"If we are successful in finding novel targets and bringing those forward," said Larry Wheeler, a senior vice president with Allergan, "then the patients will be happy, the university will be happy and Allergan will be happy."

Allergan spends about $1 billion on research and development annually.

The U. gets about 11 percent of its approximately $350 million annual research funding from private industry, said Tom Parks, vice-president for research, compared to an average to 6 to 7 percent.

While the deep government cuts known as sequestration affected federal research funding at the U. last year, he said that a ramp-up in proposals from professors means traditional research dollars are looking robust so far this year and the institution is on track to have one its best years yet.