This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Charlie McQuinn didn't think much about the cracks in the basement floor of his Cottonwood Heights home, where he maintains his office downstairs.

But that was before his doctors found a three-inch tumor in the lower lobe of the non-smoker's left lung two years ago. The culprit turned out to be radon that had accumulated in his home.

"The dryer creates a vacuum that draws the gas up through the cracks," McQuinn told a Senate committee last month in support of SB109, a bill that would establish a $100,000 statewide radon awareness campaign.

Senators unanimously passed SB109, and a House committee gave its OK Thursday, sending it to the full House.

The one-time state appropriation would replace disappearing federal funding.

Radon is a natural gas emitted as uranium and radium decay in the ground. But the colorless, odorless gas is radioactive and damages the cells lining the lungs. Radon exposure is the second-leading cause of lung cancer, responsible for 15,000 to 22,000 U.S. deaths a year.

Had McQuinn known about the hazards, he would have dropped the $10 on a home test kit a lot sooner, he said.

In the past two decades, 35,000 Utah homes have been tested.

"The average tested well above the [Environmental Protection Agency] action requirement where there was significant health risk associated with that level of radon," said bill sponsor Sen. Aaron Osmond, R-South Jordan. "It's a very significant issue in Utah and it's time for us to help Utahns become more aware of it."

His bill would appropriate $100,000 for the Department of Health to develop an electronic campaign informing the public about the dangers of radon, testing options and how to remediate high concentrations in homes.

If the campaign prevents a single case of lung cancer, it could be money well spent, backers say. The cost of surgery, chemotherapy and transfusions exceeded $1 million for Jan Poulsen, another non-smoker diagnosed with lung cancer in 2007.

She moved into her Sandy home in 1992 near the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon, known for its walls of granite — a type of rock prone to radon emissions. The Poulsens tested the home for radon and levels were safe.

But a decade later, they added onto the home and put in an entrance to the basement.

Poulsen suspects this work may have created a pathway for radon to accumulate in the home. There was a finished room in the basement, which she did not spend much time in, although she was home frequently after the work was done.

Following her diagnosis of stage 3A cancer, Poulsen and her husband retested the home. This time the reading was nearly 25 picoCuries per liter of air, or six times the safe level of 4. Poulsen paid $1,500 to have the mitigation equipment installed and the radon levels fell to less than 1.

"Had we known the dangers we would have done it when we first moved in, but it tested normal," Poulsen said.

Participation in radon testing is growing in Utah, according to Eleanor Divver, the state radon program coordinator. She said in 2011, 4,236 homes were tested and 755 had mitigation equipment installed, which costs on average $1,200.

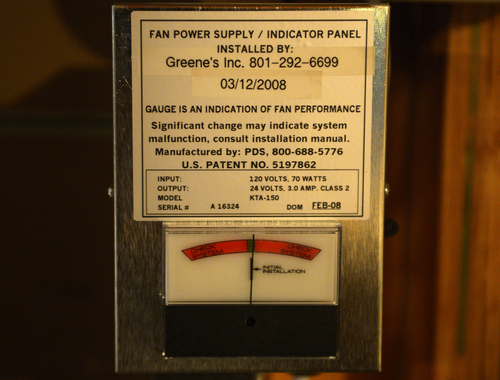

Mitigation entails digging a six-inch-diameter hole in the home's foundation. A vertical PVC pipe, equipped with a fan, vents the air outside the home when radon levels reach a certain threshold.

Utah has no radon regulations on home sales and construction and the real estate industry would like to keep it that way. Realtors, however, generally use property disclosures that indicate whether the seller is aware of radon contamination, according to Rick Southwick of the Utah Association of Realtors.

The association has given away thousands of test kits. The state also provides free testing for families with newborn babies.