This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Provo • Moreno Robins arrived at his 37-acre farm Tuesday morning and discovered one of his 20 cows had just dropped a newborn calf, which was still dripping with amniotic fluid and looking for its mother's teat.

Without that nourishment, the young animal would not survive long.

The scene reminded the retired pediatrician of what the Robins family stood to lose under one option for an ambitious federal plan to restore a slice of nature where the Provo River and Utah Lake meet. He has spent the last couple of years wondering whether his property near the lake's east shore would be taken to create a river delta that would serve as crucial rearing grounds for the endangered June sucker.

But under a compromise local landowners reached with the U.S. Department of the Interior, the preferred plan now targets a smaller tract of pasture to the north of the Robins property.

"It's not a big farm, but it's paradise," Robins said, admiring the views of the snow-covered Wasatch Mountains disappearing into a ceiling of cloud cover.

The federal Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission last month rolled out a new version of the Provo River Delta Restoration Project, which went back to the drawing board two years ago when critics blasted it as an attack on agriculture and outdoor recreation.

The earlier version would have diverted the Provo from its diked channel a mile and a half above Utah Lake State Park and turned the water onto several hundred acres of agricultural land sandwiched between a subdivision and the lake.

The new plan halves the pasture that will revert to marshlands to 310 acres and guarantees minimum flows in the lower Provo, which has become a popular green belt used by joggers, anglers and boaters.

"That's advantageous to everybody," Robins says. "That's a win-win proposition. We keep some nice land. We keep some country in Provo still."

—

The decline of June sucker • For proponents of the project, the accord shows that agriculture and endangered species conservation can co-exist.

June sucker once swarmed by the millions in Utah Lake. But the introduction of carp and other non-native fish, along with habitat degradation, much of it done to benefit agriculture, have made the lake an inhospitable place for the species.

The project's goal is to undo some of the damage done by upstream dams and downstream dikes that keep floodwaters off land now used to raise livestock. The mitigation commission intends to push the river out of the channel to form a delta — a fan-shaped marsh at a river's mouth where the flow slows, spreads into multiple channels and drops its sediments.

The lake's young suckers need such an environment for safe harbor.

"June sucker are an important indicator species. Anything we can do for June sucker makes things better for Utah Lake," says Mike Mills, who coordinates sucker recovery programs for the Central Utah Water Conservancy District.

Saving this species, which live naturally only in Utah Lake, requires fixing what biologists call a "recruitment bottleneck," the failure of naturally spawned fish to reach reproductive age.

This means ensuring young fish achieve a length of eight inches. That's far short of the two feet adults can reach, but the lake's non-native predators can't readily get their jaws around an eight-incher, Mills says.

In the mid-1990s, the June sucker population fell to less than 400, triggering two important conservation measures — mandatory water releases of 13,000 acre-feet a year from Deer Creek reservoir and captive breeding.

Artificially raised suckers in Red Butte Reservoir near the University of Utah have been used to stock Utah Lake with 400,000 adults, according to Mills.

—

Room to grow • With water in the lower Provo and thousands of adult suckers, there has been plenty of spawning. But it has accomplished little for the imperiled fish.

"The [lower] river having been channelized for so many years and dredged, it's one of the deepest parts of the lake," says Mark Holden, a project coordinator with the mitigation commission.

June sucker spawn here every spring, but when the eggs hatch, the current pushes the poor-swimming fry into slack water, where they are an easy meal for the walleye, bass and other species introduced to the lake for anglers.

Unlike Robins' calves, larval suckers never survive beyond 20 days. A recreated delta would give these youngsters a place to beef up for two seasons.

"The river is going to spread out. It will have vegetation growing up. It's going to provide places for those larvae to distribute into to avoid predation," Holden says.

"It's shallow and warm so there is a lot of production of algae and the zooplankton that feed on the algae. That's what the June sucker feed on," he says. "They grow quickly. We expect at the end of the first year they will be four to six inches."

—

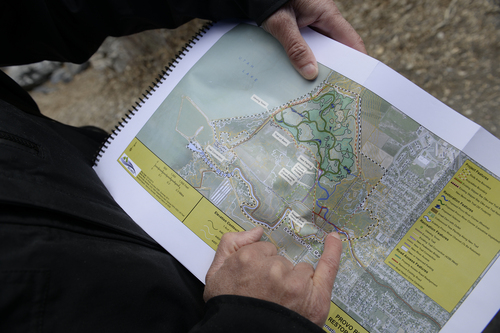

Boondoggle or boon? • The project would remove a few thousand feet of berm currently separating Utah Lake from the DeSpain property, according to a draft Environmental Impact Statement released last month. This boggy land, immediately north of Robins' pasture, would become the delta, along with property to the east owned by the Fisher family.

A new berm, featuring a trail and a viewing tower, would run inland to keep the new delta from spilling south.

Critics still feel the delta restoration is a boondoggle. But they are no longer fighting the project because its current plan poses minimal threat to agriculture and the existing river channel, according to Benjamin Allen, who owns the CLAS ropes course he established 20 years ago on river-front property.

"It's still a waste of money for the government to spend $100 million when we are trillions in debt and our economy is struggling," says Allen, who also rents canoes and runs cruises. "No one wants that fish. It's probably not even a separate species. I am reluctant to stop fighting on principle."

But proponents say the delta project will have benefits far beyond June sucker recovery, a worthy goal in its own right and necessary to ensure federal wildlife officials don't interfere with water deliveries.

The new proposal guarantees minimum river flows of 10 cubic feet per second in the existing channel and would erect a second dam that would keep the river level constant for a 1.5-mile stretch above Utah Lake State Park. This lower dam will prevent lake water from backing up into the river and enhance recreation.

Meanwhile, the delta would open up new opportunities for hiking, angling and non-motorized boating.

"It brings attention to Utah Lake and what an amenity it really is," Holden says.

Provo River Delta Restoration

Agencies plan to acquire 310 acres where the Provo River meets Utah Lake and restore braided river channels in hopes of saving the endangered June sucker, a native fish that lives in Utah Lake and its tributaries.

An open house will be held on the project April 2 at the Provo City Recreation Center, 320 W. 500 North in Provo 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. The public has until May 7 to submit comments on the draft Environmental Impact Statement by email to rmingo@usbr.gov.