This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Bruce Hardy knew that the 40th anniversary of his remarkable Bingham High School athletic career had arrived this year mainly because he was invited to the school's class reunion.

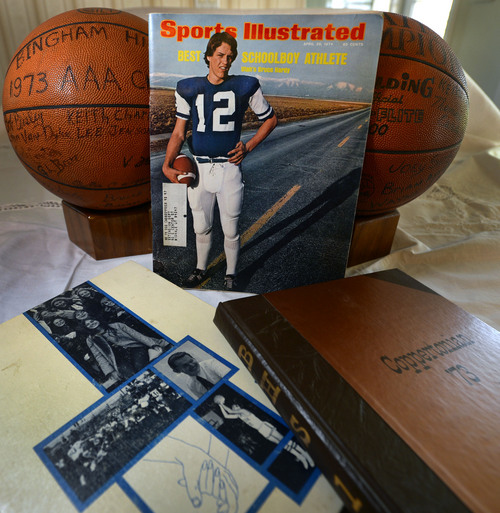

But the fact that this was the week he appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine escaped his notice.

"I was talking to my dad yesterday," said Hardy, who moved to southern Utah from Florida in 2010 to help take care of his father and late mother. "I can't believe this is my 40th high school reunion. To be honest, I didn't think about Sports Illustrated."

Friends and longtime Utah high school fans will never forget that April 29, 1974, cover. Hardy's teammate and friend, current Bingham baseball coach Joey Sato, said he still has a couple of copies around.

Hardy posed for the iconic cover shot standing on the lonely Bingham Highway in his Miner uniform clutching a football, a wheat field and the snow-capped Oquirrh Mountains behind him. The words read:

"Best Schoolboy Athlete. Utah's Bruce Hardy."

George Sluga, who coached Hardy and three-sport star athletes such as Sato and Glen Roberts to the Class 3A basketball title in 1973 and 1974, remembers picking up Sports Illustrated writer Jerry Kirshenbaum at the airport when the writer was researching the story near the end of the 1974 basketball season.

"We tried to show him some Bingham hospitality," said Sluga, who attended Bingham High himself. "He had breakfast but then rented a car and started taking care of business. I have never seen such intensive reporting. The photographer doubled the light with portable lights in Bingham for better shots."

Kirshenbaum's lead paragraph summed up the mystique Hardy had developed playing at old Bingham High in its last season before students moved into a new school in South Jordan — Bingham High's current location — in 1975.

The old school itself lent a bit of flavor to the story. Located at the mouth of Bingham Canyon, most of its students needed to drive miles from the Salt Lake Valley to attend.

Its football field was carved out of the side of a mountain behind the old brick building that opened in 1931. All that remains besides memories these days are an old set of concrete stairs leading up to a vacant lot. The gym was a classic, a bandbox affair with a few bleachers on the floor and steep seats in the balcony where the students sat.

"Bruce Hardy might have been dreamed up, along with his cereal-box name, to remind the world what an old-fashioned hero looks like," wrote Kirshenbaum. "He might have descended in Bingham, Utah, appearing in the narrow canyon in the chalk-colored Oquirrh Mountains as in a vision. Somehow it all seems too perfect that Bruce Hardy should throw touchdown passes and hit home runs on playing fields carved out of hillsides; that he should do wondrous things with a basketball in a dim, splintered bandbox of a gym; that Utah's sportswriters should hymn the praises of "Bruce Hardy and the Mountain Men."

Looking back, Hardy can't remember whether Sluga, football coach Roy Whitworth or baseball coach Son Sudbury approached him about the story. Becoming one of the few prep athletes to ever grace the cover of the prestigious magazine was mostly positive, but the immediate effect wasn't obvious then.

"The positives to me didn't come about until I got older," said Hardy, who is now a substitute teacher in Washington County after playing college football at Arizona State and spending 12 years as a tight end with the Miami Dolphins. "When I went to college, I was playing with guys I had never met before. They were all strangers obviously. I didn't know who they were, but they knew who I was. The article itself was flowery; not that they didn't say anything that was not true, but they make you out to be some super hero.

"All I wanted to do was go down and play football and get along with everyone."

The negative came because players and coaches who saw the story had higher expectations for Hardy.

"There are not a whole lot of high school guys who have the cover, so I am in pretty good company," said Hardy. "At the start, it was tough. I was still playing baseball when it came out and we had [American] Legion that summer. We played a lot of games. I took some ribbing from the other players."

Sato remembered thinking it would be a nice write-up but thought the cover was an extra bonus.

"It really didn't have much effect on the rest of us through the summer that year," he said. "We were used to having a 'celebrity' among us. However, we'd all grown up together and throughout all of his success, he was never any different to those of us who had grown up together playing all the sports. If there were any comments by our opponents, I can't recall anything that caused any issues or concerns."

The only downside was that Hardy had to leave the team to attend preseason football camp at Arizona State right before the American Legion championship. The Miners managed to win the state championship, but lost in the regionals in California.

Hardy was a throwback in other ways too. In modern American high school sports, few athletes manage to letter in three sports, much less earn all-state honors in all three.

Sluga said Hardy could have played pro baseball as well as pro football and, potentially, even basketball. In those days, Sluga said the coaches encouraged athletes to play as many sports as possible.

Hardy said that three-sport stars are rare in bigger cities, though they an be found in some rural areas. And he's not certain about the value of playing on year-round basketball or baseball traveling teams as is often the case these days.

"I do think one of the downsides to travel baseball leagues is that kids start playing at 7 or 8 and they play 100 games a year," he said. "They get to high school and they are burned out because they have played so many games. I understand what parents are doing. They are trying to get them a scholarship and even have a dream to put them into professional sports."

Hardy's four sons played little league baseball. Only one played football. Another wanted to, but was not big or fast enough.

Life hasn't been easy the past few years for the former Bingham star. His younger brother Axle, a three-sport star for Bingham in his own right, died of ALS in 2011 at the age of 53. His mother died due to complications from Alzheimer's. His father, Alan, who just turned 82, struggles with Parkinsons, but is doing much better these days.

As for his health, Hardy did need a knee replacement when he turned 50. He is well aware of the problems contemporaries such as Jim McMahon have had with memory loss due to concussions.

"My wife thinks I'm losing my memory a little bit and I probably am a little," he said. "I feel like mentally I'm OK. It's a tough sport. The league denying concussions has gone on for a long time. All that stuff. It happened."

But there were the good things too, like the memory of state baseball and basketball crowns, of driving an old car, living in the basement of the family's West Jordan home and hanging out with teammates.

And to those lucky enough to have seen Bruce Hardy play high school sports in a much different era, the memories are worth savoring.

Twitter @tribtomwharton