This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For 100 years, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts has been educating people who don't know good art from a hole in the ground.

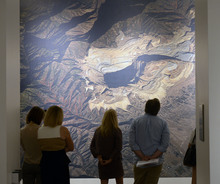

Today, as part of its centennial celebration, the museum is opening an exhibit that gathers together art works about a remarkable hole in the ground.

"Creation and Erasure: Art of the Bingham Canyon Mine" displays more than 100 works — paintings, drawings, prints and photographs — that evoke the history, industry and environmental impact of the Utah landmark, the world's largest human-made excavation.

The exhibit opens Friday, May 30, and runs through Sept. 28 at the museum, at 410 Central Campus Drive on the University of Utah campus.

The works span 140 years — from a lithograph printed in a book in 1873, when the mine was still a small hole drilled into a mountain, to aerial photos taken just after the April 2013 landslide that crossed through the familiar tiers spiraling more than a half-mile into the earth.

"This is the Bingham Canyon Mine like you've never seen it before," said Donna Poulton, the exhibit's curator (and former curator of Utah and Western art for UMFA).

At a Wednesday press preview of the exhibit, Poulton said she envisioned the show five years ago, while researching a book on Utah's West Desert.

"I kept noticing a plethora of images of the Bingham Canyon Mine," she said.

The works come from far and wide.

• A wall-size print, courtesy of NASA, features the view of the mine from the International Space Station.

• Two landscape paintings by H.L.A. Culmer, created in 1912 at the behest of Daniel C. Jackling — founder of the Utah Copper Company (which later became Kennecott Copper) — are on loan from the Utah Capitol, where they were hanging in the offices of Gov. Gary Herbert.

• A series of silver-gelatin prints, capturing images shot in the 1940s by the industrial photographer William Rittase, were stashed in a vault near the mine — and were recovered by workers for Rio Tinto Kennecott (as the company is now known).

Rio Tinto Kennecott is the exhibit's presenting sponsor. Gretchen Dietrich, UMFA's executive director, praised the mining company for its help locating those prints and otherwise supporting the show.

Dietrich said there was no corporate pressure to downplay the less glorious aspects of the mine's history.

"The show was really fully baked" before Rio Tinto Kennecott signed on, she said. "There were no compromises. They were happy to support the exhibition as it was."

Among the first images seen when entering the exhibit are those of landscape painter Jonas Lie, who first captured the mine's features during World War I.

Poulton noted the modern-art techniques Lie used to depict the mine's steam shovels — a simple line of paint to depict the exhaust, white for steam-driven shovels, black for coal-fired ones.

Photographs from the '40s, like those by Rittase or Andreas Feininger, capture the men who labored at the mines — moving earth by sweat, machine and explosives.

Poulton remarked how these photographers were among the first to employ "deep focus," so that both foreground and background images were sharp. That may sound easy to do in the age of Photoshop, but then it "was something very hard-fought," she said.

Robert Smithson, the creator of the landmark Great Salt Lake earthwork Spiral Jetty, is probably the best-known artist represented in the show. His 1973 print — made the same year he died in a plane crash — depicts a proposed reclamation plan for the mine, to be used whenever it was decided to stop digging for minerals.

"I don't think he had any idea of the longevity of the mine," Poulton said.

Juxtaposed with Smithson's work are paintings by current Salt Lake City artist Jean Arnold. They evoke the spiral patterns of the mine's many layers and suggest a kinship between the mountain that once stood and the mountain-size empty space now there.

Arnold is the only woman artist represented in the show, though Poulton said, "it's not for lack of trying."

Another famous name represented is the nature photographer Ansel Adams. A display case contains bound volumes of Fortune magazine, which commissioned Adams to photograph the mine in the 1950s.

Poulton said it was strictly a pay-the-bills gig for Adams. "He did them reluctantly," she said. "He would rather be in the national parks."

Other modern photographers — Edward Burtynsky, David Maisel and Michael Light are all represented here — capture the eerie beauty of the human-made landscapes.

And the exhibit includes a photo by artists from the Center for Land Use Interpretation, shot from a helicopter two days after the landslide on April 10, 2013, changed again the mine's topography.

"It changed the image [of the mine] that we know," Poulton said. "Suddenly the entire landscape changed."

One room of the exhibit is an interactive experience, something Virginia Catherall, UMFA's curator of education, said aims to convey the history, science and art of the Bingham Canyon Mine.

The interactive exhibit includes displays of historical artifacts from the mine, art objects made of the minerals (gold, silver, copper) extracted from the mine, and even audio of the 2013 landslide.

"When you hear it, it's like a train wreck," Poulton said.

Twitter: @moviecricket —

A rich vein of inspiration

"Creation and Erasure: Art of the Bingham Canyon Mine," an exhibit of more than 100 works about the Utah landmark.

Where • Utah Museum of Fine Arts, 410 Central Campus Drive, University of Utah campus, Salt Lake City.

When • Opens Friday, May 30, and runs through Sept. 28.

Hours • Tuesdays through Fridays, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. (open until 8 p.m. on Wednesdays); Saturdays and Sundays, 11 a.m.-5 p.m.; closed Mondays and holidays.

Admission • $9 for adults; $7 for youth (ages 6 to 17) and seniors; free for University of Utah students, staff and faculty, UMFA members, college students and children under 6.