This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Washington • In the thick of the Great Depression, Time magazine sported a cover story of a Utahn whom President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had tapped to help calm the markets and revive the tanking economy.

"A good many people believe that Marriner Eccles is the only thing that stands between the United States and disaster," the magazine declared in 1936.

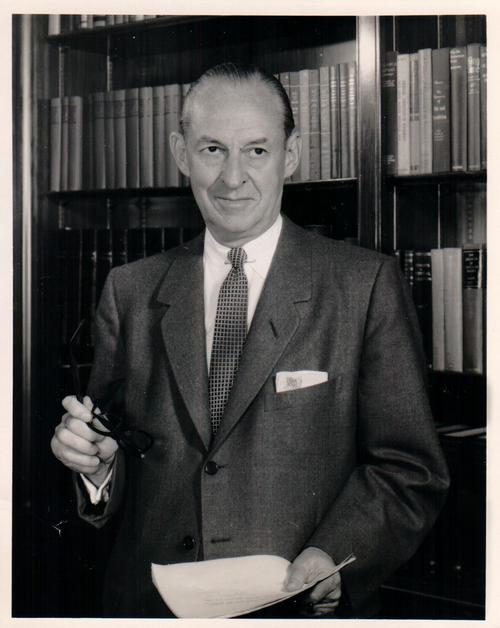

Decades later, Congress named the Washington headquarters of the Federal Reserve after Eccles, widely credited for ensuring the central bank remained independent from political whims and private interests and for his policies that helped turn the corner from the Depression to a prospering country. It's the only building in Washington named after a Utahn.

On Wednesday, in a private ceremony, the Federal Reserve will further honor Eccles, unveiling a statue of the former Fed chairman whose legacy is still the hallmark of U.S. monetary policy. Though the Eccles name is plastered across Utah on buildings named after the family, Marriner Eccles may not be as well known as he once was.

But his legacy is a source of pride for Eccles family members, who say they're honored to see Marriner Eccles recognized again.

"It's true; the full story has never really been appreciated by a broader base and now we've got new generations," says his nephew Spencer F. Eccles, a prominent financier and philanthropist. "But the facts of life are a lot of these things that are bedrock for the Federal Reserve, and for the economy and for the economic philosophy emanated during that period of time and Marriner had strong theories that he had arrived at, and defended and put them into action."

Marriner Eccles never got to push the government as far as he'd like, and it wasn't until the beginning of World War II that deficit spending helped fuel the economic bounce that he was hoping for.

"There's no question by those who are scholars and know the facts, [that he was] … terribly important at the time, critically important at the time, especially during the depths of the Depression when this country was flat on its back," says Spencer Eccles.

In the building-naming ceremony in 1983 — six years after Marriner Eccles' death — he was heralded as a visionary.

"Marriner Eccles has been identified with American monetary policy perhaps more than any figure of his time," the program proclaimed. "He remained a staunch defender of the independence of the Federal Reserve throughout his career. It has been said of him that, whether in public service or in private enterprise, he displayed a shrewd realism about the course of the American economy.

"History has proved his judgments accurate on many political and economic issues," the biography read.

Eccles was born in Logan in 1890. After his father's death, he consolidated the family's banking and business interests and helped build First Security Corp.

His success earned him an invitation to speak in 1933 before the Senate Finance Committee, where Eccles' candid suggestions for improving the economy caught the ear of Roosevelt, who named Eccles as an assistant secretary of the Treasury Department. Within a year, Roosevelt tapped him to head the Federal Reserve.

It's there that Eccles helped revolutionize the way the U.S. government handled monetary policy and helped create the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., to protect Americans' bank accounts, and the Federal Housing Administration to boost mortgage investments.

A Scripps Howard cartoon at the time showed a man holding a U.S. coin with the word "God" scratched out from the money to then read, "In Eccles We Trust."

Eccles was also a champion of the school of thought that would later parallel those pushed by John Maynard Keynes, essentially that government intervention, such as action by a central bank and fiscal support by the government, are needed to stabilize the private sector.

"Marriner had gone to Washington some 25 years before I met him — a banker and a businessman with fresh and strong views about how to deal with the depression," Paul Volcker, a former Fed chairman, said during the 1983 ceremony naming the building. "Among other things he could be said to have found Keynes' theories before Keynes — his lesson was that deficits are not always a bad thing. Sometimes I think we learned that lesson too well."

The private ceremony Wednesday at the Eccles Building in Washington is closed to the press but expected to draw members of Utah's congressional delegation as well as Eccles family members.