This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Under a late-afternoon sun, shadows and light begin to unlock the mystery on Clint Buffington's seemingly blank piece of paper.

The message has faded since a young sailor scrawled his contact information on the paper and popped it in a bottle. The man was drifting into his 20s, a world away from home. He tossed the bottle into the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and waited for destiny to call back.

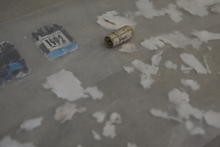

"It looks like the first number is a four," Buffington says on his Salt Lake City porch, squinting in search of faint pen impressions — all that remains of the message in a bottle that washed onto a beach Buffington was exploring two years ago on a remote island in the Caribbean.

This is Buffington's 60th such bottle. He has deciphered dozens of messages torn and sun-bleached beyond intelligibility, and he knows where to look for clues. But A-ha! moments still occur, and he's about to have a big one.

"It's either a four or a plus sign, then 63 —"

A plus sign! That could indicate a country code in a phone number. Google country code 63 ... Philippines?

That's weird.

Since Buffington found his first bottled message on a family trip to the Turks and Caicos Islands in 2007, the writing instructor-farmer-musician has learned a lot about ocean movements.

His collection, all from about five tiny islands, has attracted the interest of at least one oceanographer, and his bottles' origins — from a Pennsylvania river to the Azores — reflect a rotating north Atlantic current that does not include the Philippines.

But there, in the corner, Buffington can make out imprints of the word, "Philippines." To the left is another p-word. Pelican? A "y-l-e" comes into relief below. Somebody named Kyle, perhaps?

"But that's definitely an 'Andy,' " Buffington says, pointing at the center of the note.

Identifying the sender is the fun part, Buffington says. Of the 60 bottles, he's made contact with 15 senders and personally met four of them.

"It's become a passion to reconnect [the bottles] to the senders and meet new friends," he says. "These people would be strangers."

Buffington's first bottle, found in 2007, was easy — a souvenier launched just one year earlier from the mid-Atlantic by a Canadian couple on a cruise ship from Madeira, Portugal.

The older bottles are more of a treasure hunt.

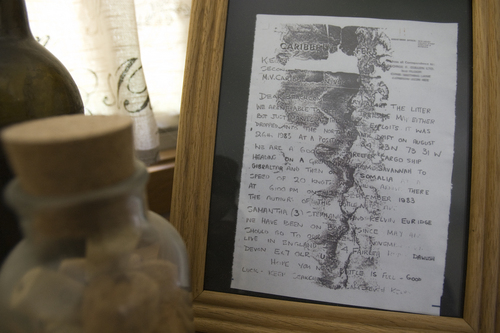

On his living room wall, Buffington has framed the fragments of a letter he found shredded inside a bottle on his 2011 return trip to Turks and Caicos. He fit the faded puzzle pieces together to find the names and address of a young British family of three who were traveling on a cargo ship from Savannah, Georgia to Gibraltar, near Spain

The letter was dated 28 years earlier, when the daughter was 3 years old.

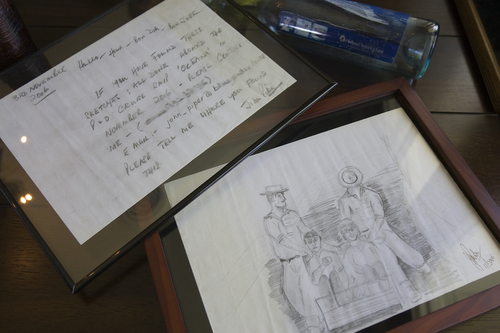

Buffington searched for the family through changed addresses and a divorce, and ultimately found the father in Devonshire, England — coincidentally just a few miles from the home of an artist whose 2006 bottle, stuffed with drawings and launched from a Caribbean cruise found its way to Buffington's collection in 2008.

Upon hearing from Buffington, the artist sent him a painting that now decorates his wall.

Buffington's most challenging reunion required calls to a chamber of commerce, a county clerk and a tax assessor in New Hampshire to find the daughter of a couple who sent a bottle from their seaside inn in Hampton at least 40 years ago, and since have died.

This newest message is far easier to trace. Online searches for pelicans, Andys and Kyles in the Philippines turn up a Facebook profile for Andy Pelicano.

With new information, the brain can see more words in the pen scratches. What first appeared to be "Kyle" is, on second look, Leyte — Pelicano's home island and province. Soon a hodgepodge of curves and lines come into focus as "Palompon," Pelicano's city.

According to his on-line profile, Pelicano worked for a shipping company, which explains his travel in the North Atlantic Gyre, the series of currents that propel flotsam to the Caribbean.

Buffington's collection has the potential to tell scientists more about the Gyre's behavior, said oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer.

"[Buffington] has perhaps the best data set of bottles collected at one small spot, which is really unusual," Ebbesmeyer said. "There are many studies of [items] being released at a certain spot, but what fascinates me even more is how the ocean gathers stuff from all over. Bottles from Greenland, Spain, New York, all over the north Atlantic, wind up there at that little island group. How does the ocean do this?"

Ebbesmeyer, author of the book "Flotsametrics" and the blog Beachcombersalert.org, says the dates and locations of bottles sent and found could contribute to climate science by showing how ocean movement may be changing over time as the earth warms, sea levels rise and coasts erode.

"What beachcombers find can have very high scientific significance," Ebbesmeyer said. "I want to know what the ocean is telling us, and she speaks with flotsam."

But for Buffington's most recently opened bottle to speak, he still needs to find its launch date and place of origin.

After sending messages to Pelicano and several of his relatives, The Tribune learned he is working on a ship's crew near Scandinavia.

Pellicano declined to be interviewed, but relayed through his cousin that he launched the bottle four years ago while working somewhere near the center of the Atlantic Ocean.

"He is happy and surprised," the cousin, Kaya Guatche, said. "[He] really didn't expect that someone could find that bottle. ... He was [younger] when he threw that bottle. Maybe that message is full of hopes and loneliness."

Pelicano now has a fiance and a young son to greet him after his sea voyages, Guatche said.

His message to the Atlantic is now framed in Utah with 59 other destinies sought.

Making connections

Bottle-finder Clint Buffington acknowledges that throwing a message into the sea is littering. But people will continue to do it, he says, so he offers some tips to minimize impact and improve the likelihood of a reply.

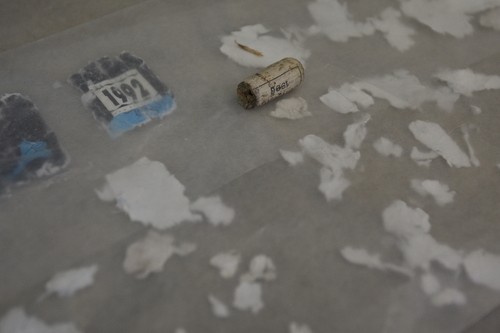

1. Use a glass bottle, not plastic, which degrades quickly to a damaging pollutant. Buffington points to a plastic message bottle that was falling apart around a message just a few years old. He compares that with a fully intact message in a glass Guinness bottle the Irish beer company threw into the sea in 1959 as a promotional stunt. Lightly colored glass offers some sun protection while keeping the message visible to beachcombers.

2. Use pencil rather than pen, and press down hard to create impressions in the paper. Ink bleeds and fades in water and sun.

3. Seal the bottle with cork or metal. Plastic and rubber deteriorate.

4. Roll the message and tie with string to make it easier to remove potentially fragile paper.

For more information and stories of bottles found, visit Buffington's website: messageinabottlehunter.wordpress.com.

To report any interesting findings from your seaside travels, contact Curtis Ebbesmeyer at beachcombersalert.org