This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

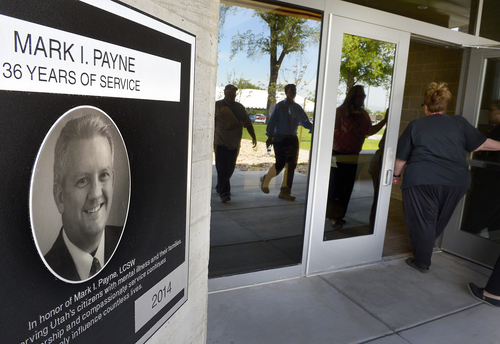

During his 12 years as superintendent of the Utah State Hospital, Mark Payne often walked the hospital grounds, reflecting on the importance of preserving the peaceful, therapeutic mountainside setting.

Later, as director of the state's Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, he fought for funding to upgrade and repair the hospital's aging buildings. Funding was delayed by a legislative push to privatize the hospital, but eventually came through for two facilities — after Payne's sudden death in 2010 from heart failure.

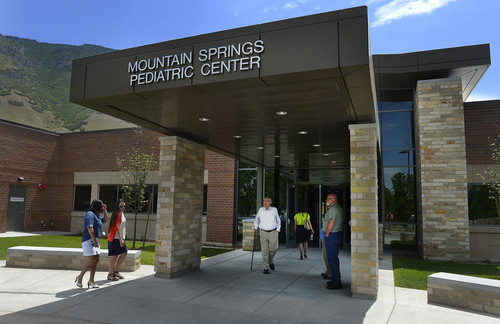

Hospital staff celebrated the opening of those buildings Thursday, dedicating one to Payne.

"Mark cared about every aspect of this campus, even down to the old trees planted in the late 1800s and early 1900s," said the hospital's current superintendent, Dallas Earnshaw, at a ribbon cutting. "If you notice how the buildings are kind of cattywampus from the road, it's because we built them around the trees."

The new buildings — the Mark I. Payne Building, a medical services center, and the Mountain Springs Pediatric Center — don't expand capacity, but consolidate and replace several older buildings that posed safety problems for patients, said Earnshaw.

"Steam pipes went through cement walls and there was so much rust and corrosion that we couldn't get heat to the rooms," Earnshaw said. "Office staff would have pipes above their heads break, flooding their desks."

Created in 1885 by the Utah Territorial Legislature, the state hospital has grown from an asylum, or holding place for the severely and persistently mentally ill, to a progressive treatment center.

Utah has the nation's highest rate of mental illness, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. About 22 percent of adults report having mental illness of some kind, including depression. For serious mental illnesses, Utah has the third highest rate, at 5 percent.

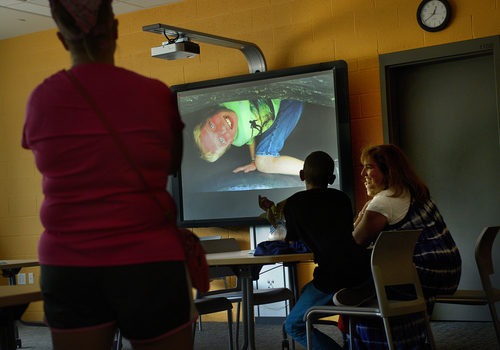

And more children are being diagnosed with severe behavioral problems at earlier ages.

Yet demand for services at the state hospital hasn't grown, largely due to federal guidelines created to discourage institutionalization in favor of community-based care.

"We're putting more resources into our communities, [such as] prevention efforts so we can keep families together," said Doug Thomas, state substance abuse and mental health director. "Utah State Hospital is not a landing pad. It is a launching strip where people come and get well and take off to pursue their dreams and hopes."

But Keri Herrmann, a child psychiatrist and pediatric director for the hospital, added, "The kids we see here are a lot sicker than 10 to 15 years ago."

There are currently 55 children and adolescents in the 72-bed pediatric center.

A third come through the foster care system and have experienced abuse and trauma.

Between 30 and 40 percent have developmental disorders, such as autism, Herrmann said.

They have on average three diagnoses of major mental illness such as psychotic and mood disorders, in addition to anxiety and depression.

And they come to the hospital — spending nine months on average — when community supports fail to address their needs, said Herrmann.

"It was the right place for me," said Joseph Ott, who spent three years at the hospital's forensic unit as a youth. "I was the person you'd want off the streets…in and out of jail and self-medicating with alcohol and street drugs."

It wasn't until he landed at the hospital that Ott realized he was sick with schizophrenia and a personality disorder.

"I thought everyone felt suicidal on a daily basis. I thought that everyone heard voices telling them what to do," he said.

Through therapy and with medication, Ott said he learned how to manage his disease.

A father, grandfather, church volunteer and the voting consumer representative on the hospital's board, he said, "I still have my ups and downs, but I'm able to function as close to normal as possible."

Ott keeps a brick from the old forensic building on his living room table. It and the original iconic white, brick asylum on the hill were razed years ago.

The new medical services building replaces a facility built before Payne was born and will house health clinics, substance abuse programs and a pharmacy.

The pediatric center will replace two buildings, bringing the dorms, school and therapy rooms under one roof.

Twitter: KStewart4Trib