This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On a muggy June afternoon in Carthage, Ill., exactly 170 years ago, a mob of men stormed up the stairs of a makeshift jail and murdered a Mormon prophet.

That day — June 27, 1844 — is pivotal in LDS history, marking the end of the faith's founding era and the beginning of its exile and exodus to Utah.

But it merits no more than a footnote in most American history textbooks, says Boston Globe columnist Alex Beam.

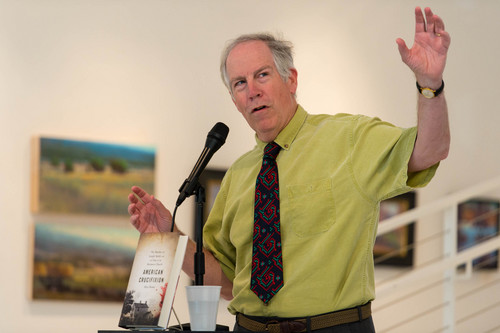

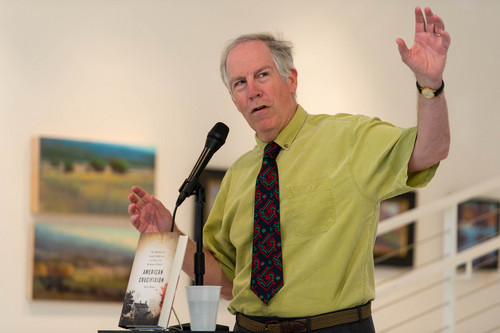

And that is unfortunate, says Beam, author of "American Crucifixion: The Murder of Joseph Smith and the fate of the Mormon Church."

Smith's assassination — known to LDS faithful as "the martyrdom" — is a "huge moment in the history of the American West, but also in the nation itself," the writer, who is not Mormon, says in an interview. "I'm not sure there's another incident in American history where a major religious figure was killed because of his religion."

Though the episode is "without parallel," Beam says, its neglect in the country's self-awareness has to do with "the marginalization of Mormons."

Smith's demise is considered an "oddity in American history," he says. "In most accounts, Smith is seen as a strange guy who had a bunch of followers and then was killed."

For Beam, the slaughter of the Mormon founder — as well as the conflicts leading up to it — provides rich insights into the dynamics of the native-born faith, the country's failure to protect religious freedom for unpopular churches, and mob violence in the 19th century.

"Here's a guy who believed in the American Constitution and the country's institutions like courts," Beam says. "And here's a country that's always talking about the freedom of religion. Yet he was essentially killed for talking about his religion."

And Smith was not just gunned down by a mob of hooligans, Beam says. His murderers included "a prominent newspaper editor, a state senator, a justice of the peace, two regimental military commanders, and men who just a few months before were faithful members of Joseph's church...'respectable set of men.' "

They could have imprisoned him or chased him back to old enemies in Missouri, he writes. "Instead, they chose to kill him."

Smith's actions and choices during his final days and weeks might also surprise some Mormons, who mostly see the man they call "Brother Joseph" through a mythic prism — and his death as the capstone of the persecution complex that is etched into the Mormon identity.

Creating an outsider movement • In 1830, Smith, a one-time farm boy in upstate New York, organized a new Christian church, claiming that all other denominations had lost true Christianity. Smith said an angel named Moroni had directed him to find plates of gold, on which were written the history of a Hebraic family that migrated to the Americas and whose descendants were visited by the resurrected Jesus Christ. Smith reportedly translated the ancient writings into the Book of Mormon.

It didn't take long for opposition to arise among skeptics and offended Christians.

Smith was derided as an impostor and a "money digger,'' but his book of scripture hit a responsive note with many New York believers seeking a return to primitive Christianity stripped of cumbersome rituals.

Within 14 years, Smith's followers numbered in the thousands. They were chased from state to state, upbraided for their theological innovations, their political unity, communal economics, and, finally, their social arrangements, including patriarchal polygamy.

Smith presided over "The City of the Saints" in Nauvoo, Ill., where he became mayor, lieutenant general of the Nauvoo Legion, proprietor of the Nauvoo Mansion House (including its lucrative liquor monopoly), and even ran for U.S. president.

It was a time of great flux — and secrecy — among Smith's closest circle of friends, Beam writes, and even greater animosity from Illinois neighbors, including Thomas Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal and "professional Mormon hater."

By 1844, the antagonisms from Illinois neighbors and former Mormons boiled over into violence.

Several former Mormons, including William and Wilson Law, published an edition of the Nauvoo Expositor, detailing Smith's secret polygamous relationships – including allegations that he had approached William Law's wife and some teenage girls.

Smith was outraged by the paper and ordered the press the Laws had purchased to be destroyed, and the order was carried out. The Laws filed a claim against Smith in the state court at Carthage, and Smith was arrested.

He gave himself up amid promises by then-Illinois Gov. Thomas Ford that he would be safe.

"It was kind of a biblical story," Beam says, "with people begging him not to go."

But the Mormon leader, who initially planned to flee, had gotten himself out of other legal scrapes and thought he could this time as well.

The end of days • In the last weeks of Smith's life, Beam says, "he acted a lot like a human being in trouble — with parallel circles of woe bedeviling him."

The real opposition, though, came not from the few former Mormons, but from the growing opposition in counties surrounding his City of Saints.

"He was a little overconfident, and a little under-perspicacious," Beam says. "His enemies, with their dark shadows, were suffused with hate — and they have no interest in fighting fair or going through the judicial system."

They killed the Indians, and now they are going to lynch the Mormons, Beam says.

"This was an era of violent politics," says Richard Bushman, pre-eminent Smith biographer and Mormon historian.

Newspaper writers often used "cut-throat language," he says, and described Mormons as "an unscrupulous, schismatic religious people."

An armed mob was just one of the "critical weapons" at the opponents' disposal, Bushman says.

But all the reasons why the Mormons' enemies claimed to oppose the new faith didn't add up to such visceral hatred.

Bushman, author of "Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling," explains the opposition as "moral panic."

Traditional Christians at the time "felt their way of life was in jeopardy," the historian says."It pushed them into extreme measures."

And they honestly feared that the death of the Mormon prophet would lead to violent retribution from the sorrowful Saints.

But it never happened.

Collective mourning amid resolve • On the morning of June 28, 1844, the bodies of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, who was also killed in the jail, were taken by wagon from Carthage to Nauvoo, where more than 8,000 believers lined the streets for a glimpse of their fallen leaders.

There were "groans and sobs and shrieks," one journalist reported, "'til the sound resembled the roar of a mighty tempest, or the slow, deep, roar of the distant tornado."

But there were no reprisals.

Before long, Brigham Young became the faith's new leader and directed the entire movement on a 2,000-mile journey across the plains to the Great Basin.

"The people missed Joseph's charisma, but all the strength and energy of the church didn't come from a single leader," Bushman says. "They [the Mormons] did have a feeling of deep resentment that the nation had failed them and that there would be no succor from any official source."

The peaceful transition to a new prophet and a new home was a credit to Smith, Bushman says. "The core of people were desperately loyal to Joseph but they were converted to the church, not to the man."

Smith's accomplishment was "to have created a religion," the historian says, "not just a fan club."

The Mormon leader's death "did not paralyze the Mormons," Beam writes. "Instead, it galvanized the Saints, strengthened them in their beliefs, and propelled them westward to a new, thriving 'Zion.' "

Today's Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints "stands atop the modest gravestone of a 38-year-old preacher."

Joseph was "the Saints' living, breathing, wrestling, drinking, sermonizing, truth-telling champion," Beam writes. "No one in Nauvoo didn't know him."

Every Mormon man, woman and child, he writes, "had uprooted himself or herself, and their families, either because of Joseph Smith's preaching or because they had read the sacred Book of Mormon."

But they followed the Mormon visionary not because he talked to God, Beam says, but "because he talked to them."

@religiongal —

Written word

Excerpts from Alex Beam's "American Crucifixion: The Murder of Joseph Smith and the Fate of the Mormon Church":

"In 1843, the eager-to-please council awarded the town's liquor monopoly to...Joseph's Nauvoo Mansion. 'A hotel that is a temperance house cannot support itself,' was Joseph's rationale, speaking as an innkeeper and not as the revealer of the Word of Wisdom, 'and if anybody needs profits, I do.' "

"Thomas Ford speculated that a future Church of [Jesus Christ of] Latter-day Saints might swell to many times the size of the tens of thousands of members it claimed in 1844...Should that occur, Ford wrote, 'the humble governor of an obscure State, who would otherwise be forgotten in a few years, stands a far chance, like Pilate and Herod, by their official connection with the true religion, of being dragged down to posterity with an immortal name."