This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Pleasant Grove

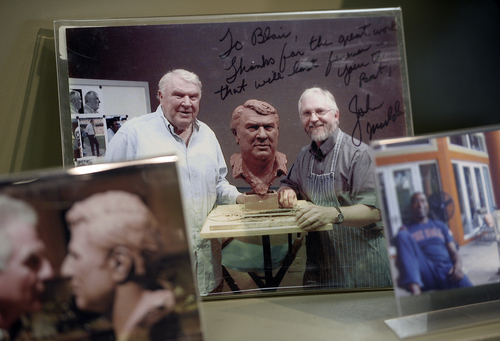

Do what some of the most famous sports figures on the planet have done — roll up on the parking lot outside of Blair Buswell's workplace here in Utah County, park your car on the same patch of asphalt where John Madden once idled his infamous bus, the "Madden Cruiser," while the coach/broadcaster sat inside for a day, posing for his Hall of Fame bust, and try to spot the sculptor's studio.

Good luck.

In a row of nondescript and unremarkable yellowish-brown town-warehouses, if there is such a term, wedged between a machine shop and a storage space, is the spot where the notables come, one by one, to be immortalized, where they visit Buswell or from where he arranges to go visit them to be measured, replicated and bronzed.

The list of immortals is impressive: Jack Nicklaus, Oscar Robertson, Jerry Rice, Joe Montana, Steve Young, Barry Sanders, John Elway, Dan Marino, Eric Dickerson, Emmitt Smith, Troy Aikman, O.J. Simpson and a hundred more — not just athletes — have all spent hours and hours with the man as he worked his craft.

To break up the time, Terry Bradshaw once fired spirals at Buswell, causing the artist's hands to swell. Charlton Heston, the actor who as Moses parted the Red Sea, got stuck in a studio bathroom, unable to solve a child's lock on the doorknob, and screamed for help. Thomas S. Monson regaled the sculptor with inspirational stories. Bill Walsh gave Buswell life advice, shaping the artist's career as much as the artist shaped a replica of the former 49er coach's mug.

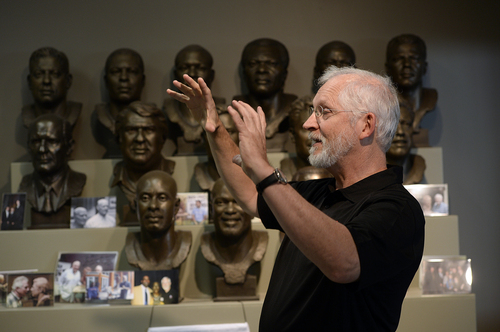

In total now, Buswell has captured the images of 85 football Hall of Famers, including four busts of the most recent class inducted in Canton last week. A walk through his studio is a walk through time, that space being filled with bigger-than-life models of Mickey Mantle swinging a bat over here, John Wooden standing with his arms folded and a program rolled in his hand over there. Against a wall is Nicklaus' famous pose at Augusta in 1986, after draining a dramatic putt, his flat blade hoisted in the air by his left hand. The finished products sit outside respective stadiums, arenas and inside museums.

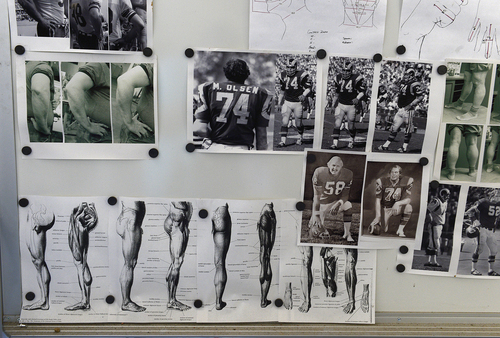

Against another wall is Robertson dribbling a basketball, a work that in finished form stands on the University of Cincinnati's campus. A kneeling model of Robert Neyland, who coached at Tennessee from 1926 to 1952 and whose name is on the Vols' stadium, is a remnant of Buswell's bronzed statue outside the stadium. Between the two is an oversized model of Merlin Olsen, a piece of art created by Buswell for a statue of the late Aggie great that now resides at Romney Stadium. Somewhere in the studio is an image of Bear Bryant, and also the model crafted for the statuette used for the Doak Walker Award.

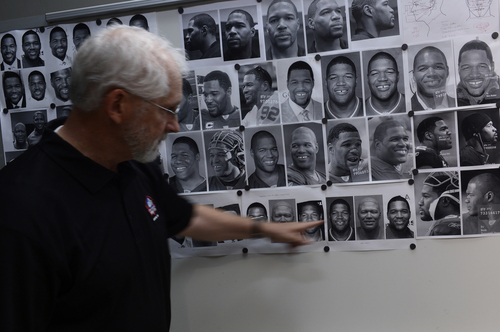

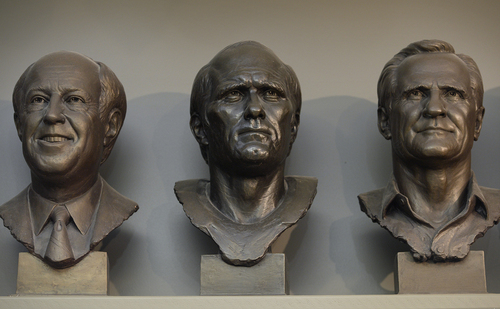

Upstairs, there's a collection of more mock-up busts of the bronzes lined in the Hall at Canton, images of the football greats Buswell has created: Pete Rozelle, Dan Dierdorf, Al Davis, Shannon Sharpe, Rod Woodson, Carl Eller, Fred Biletnikoff, Ray Guy, Alan Page, Sid Gillman, among so many others.

Mixed with all of that is a 60-foot model of a huge wagon pulled by four giant mules, with pioneers hanging onto the wagon, pioneers that happen to look exactly like Buswell and his family. "Well, they had to look like somebody," he says. "I used my wife and kids as models, and, then, I felt weird having a stranger take my family across the plains, so … I included myself." That finalized piece, along with a 75-foot conglomerate bronze of other pioneers and wagons and oxen, was commissioned by a bank in Omaha and now stands in a park there.

On this day, though, Buswell himself does not look like a pioneer. Decked out in baggy shorts, a Pro Football Hall of Fame golf shirt and flip-flops, with a ruddy face surrounded by white hair up top and a white beard below, completed with wire rim glasses, the 57-year-old's look shouts precisely what he is — a sculptor. A sports sculptor.

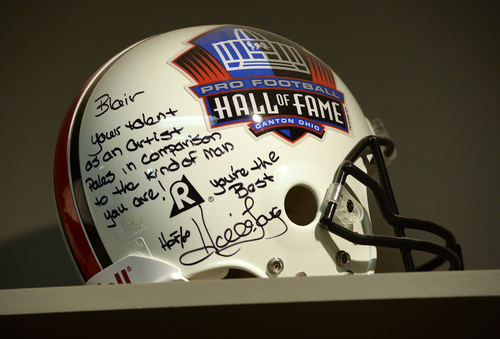

Buswell is meticulous in his work, but easy in his demeanor. That easiness helps him when working with the subjects he depicts, most of whom have never had statues crafted after them. Some of those subjects have no idea what to expect from the experience. Some want more hair added. Others want their hair or beards cut down of off. Madden wanted those dated lamb-chop sideburns subtracted. Deion Sanders wanted his doo-rag included, which was not permitted by the Hall of Fame. Buswell says some of them are edgy and anxious, others are humble and completely cooperative.

"Marcus Allen was nervous because he thought I was going to pour plaster over him and stick straws up his nose so he could breathe," Buswell laughs. "Bradshaw was great, kind of all over the place. At one point, he got a little uptight and wanted to go out and throw a football.

"I try to help these guys feel comfortable. And then I try to capture their essence, not just measure their eyes, nose and ears, but to get to know them and show with their features and expressions who they are. One of the best compliments I ever got was when the Mantle statue was unveiled, and a lot of his old teammates were there. One of them told me, 'I didn't even have to look at his face to recognize him, I already knew, from that swing. You caught the essence of the Mick.'"

When Buswell met with Simpson, back in the 1980s, he spent the day with O.J. and his late wife Nicole, and got to know them well enough that L.A.P.D. detectives called him 10 years later after Nicole was murdered to question the sculptor about what he observed in their relationship.

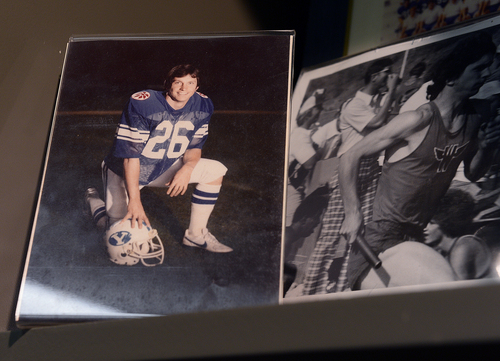

A bookshelf on the studio wall reveals who Buswell is. It has pictures of him with all kinds of athletes and coaches, but it also has a book about Bernini. Those are the two worlds in which Buswell has found his calling. He grew up in North Ogden, wanting to be an artist, but he also played football, eventually going to BYU as a running back during the Wilson-McMahon-Young-Bosco years. "I was the only football player there on an art scholarship," he says.

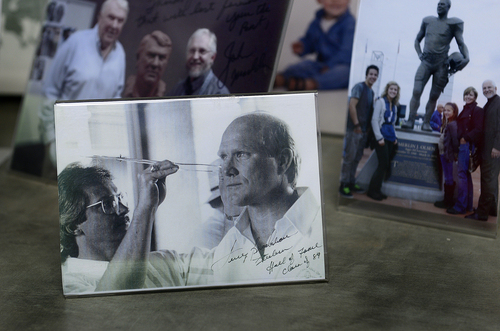

In 1982, Buswell did a bust of Bill Walsh, who was impressed enough with the young sculptor to have him also do a piece on Eddie DeBartolo. When Buswell presented his work to the then-49ers owner at his home in Ohio, DeBartolo was so pleased, he said: "You've done something nice for me, now, what can I do for you?"

Buswell says it was like having a genie appear and grant three wishes. Besides getting a stack of 49ers Super Bowl gear, the sculptor told DeBartolo he always wanted to work for the Football Hall of Fame. When DeBartolo pulled some strings, that wish was granted. Buswell has been doing the Hall's busts for more than three decades now — up to four a year. And many other projects, alongside.

He fondly remembers a conversation he had with Walsh, a brilliant football mind and also a sometimes-persnickety perfectionist, when Walsh was posing for a piece in a San Francisco hotel at the commencement of the sculptor's career.

"Bill asked me what I wanted to accomplish," Buswell says. "Then, he said, 'You can focus on making money or you can focus on improving and doing the best work you can do. If I were you, I'd be the best I could be, learn my skill — you have the talent — and get better and better. That way, when your name is brought up, quality is what people will think of. The money, that will come.'"

The quality and the money have come for Blair Buswell.

"I've been pinching myself now for 30 years," he says. "I couldn't have imagined the people I would meet, the places I would go, the things I would do. It's been unbelievable. Yeah, unbelievable."

GORDON MONSON hosts "The Big Show" with Spence Checketts weekdays from 3-7 p.m. on 97.5 FM/1280 and 960 AM The Zone.