This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The world inside Ken Sanders' bookshop ties Utah firmly to its past, just as the white-brick building on 200 East in Salt Lake City anchors a dozen other quirky stores on that downtown corner.

Sanders, 62, has stuck at the location for 17 years, solidifying his business steadily while price-smashing digital sales and retail chains wiped out most stores like it. Now the shop and adjoining vintage and specialty outlets have to move after residential developer Ivory Homes leased the land from the owner and told tenants it plans to build.

"Am I happy about it? No. But we've got time," Sanders said in a recent interview at his store at 268 S. 200 East. "I can make this happen, but I need help. I can't completely reinvent myself because I'm too damn old."

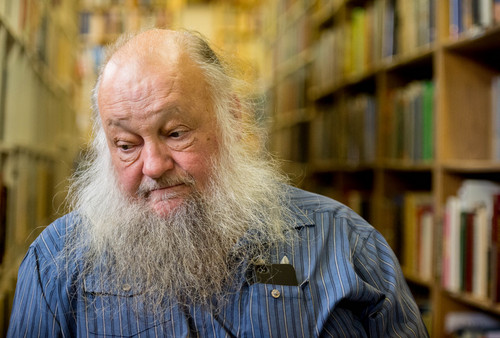

Any move for the venerable bookstore is three years or more away, but Sanders already has informed its ardent customer base, through the shop's blog, to dispel nascent rumors it might be going out of business. There's been an outpouring of support. With his long graying hair and beard, mischievous aura and sheer staying power, the store owner is an icon on Utah's underground scene, which surprises him.

"Somehow," said Sanders, whose retail history stretches back to the city's first psychedelic shop, the Cosmic Aeroplane, in the 1970s, "I've become an institution, right or wrong."

Ivory Homes is contemplating a mixed-use development on the half-acre site, possibly with office space, retail and a sizable number of apartments, according to Chris Gamvroulas, who heads the company's development arm. Exactly what the overall project will look like remains an open question, he said.

"There are a number of equations and variables we haven't started to crunch yet," Gamvroulas said. "We're not in a rush to try to do anything right now."

The site has a D1 zoning, a designation unique to Salt Lake City's central business district, which allows for more dense, multistory construction. "If you're going to build there," Gamvroulas said, "you're going to have it feel like an urban core."

For now, the neighborhood retains a funky feel that contrasts with the bland state office towers on the south side of Broadway. To one of Sanders' neighbors, the area has followed a typical pattern of gentrification: Artists are drawn to cheap, disused areas of town, followed by art galleries and small shops, and then, developers.

"It's sad because it's a wonderful neighborhood and Salt Lake is going to miss it," said Ron Green, proprietor of the Green Ant vintage furniture outlet, "but it's inevitable."

A downtown advocate said the city needs to rethink policies toward urban development, especially as the heart of Utah's capital undergoes a historic surge in new construction of apartments and condominiums.

The city's elected leaders and planners have sought new residential projects downtown for years, said Jason Mathis, executive director of the Downtown Alliance. "But how do you preserve the authentic nature of neighborhoods while encouraging high-density residences and more vibrancy?''

It's hard to imagine re-creating Ken Sanders Rare Books in different digs, but the owner is looking at other properties and sizing up what a move will mean. Change won't be easy, he said, "but we're starting a transition to the next generation."

Sanders lovingly calls his establishment "a far distant corner of the universe." Ragged stacks of antique books, used paperbacks and sundry artifacts envelop customers as they peruse its narrow aisles or settle in worn chairs and read.

That odor amid the crammed shelves, Sanders says, "would be the smell of decaying paper."

The longtime shopkeeper's persona fits the store. He's part savvy businessman, part Old Testament hippie, part historian and full-on literary scholar with a knowledge of the region's writing legacy so deep it spills out of him.

Within 10 minutes of conversation, Sanders tosses out insights into authors Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and Neal Cassady; poet May Swenson; filmmaker Trent Harris; and young artists Leah Bell and Trent Call. While he chats, someone ventures into the store with an old set of Western history books, sold by 19th-century door-to-door tradesmen.

Sanders examines the tomes, notes their poor condition and points the would-be seller to a nearby thrift store. "This isn't a widget factory," he confides later. "I could have offered him $25 but then what on Earth would I do with the books?"

Online sales have sliced margins on the book business ever thinner, Sanders said, particularly the vast Web retailer he refers to disdainfully as "Damn-azon." But the Internet, he said, also has fostered and widened allegiance to his shop.

Sanders said low rents charged for his current locale and its easy access to off-street parking have helped the shop survive. He doubts he'll find a deal as sweet. He said he needs 4,000 to 6,000 square feet to hold an inventory of more than 100,000 books, along with maps, photos, posters, postcards and other collectibles.

"We're not mall people," Sanders said, referring to Weller Book Works' move from Main Street to Trolley Square, "even if we could afford it."

A smaller footprint, he said, may mean giving up a browsing section for the store's legendary paperback stocks or scaling back on regular author appearances, poetry readings, art exhibits and other gatherings. Seeking out a comparable or bigger space, though, may pull him away from downtown to find less expensive rents.

"After a certain point," Sanders said, "you can't pretend you're downtown anymore."

Twitter: @Tony_Semerad