This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah's path to the Common Core began with a math problem.

In 2002, the state school board adopted a new framework for the math skills kids should learn each year, figuring it would guide Utah classrooms for a decade.

But the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank, gave Utah's locally developed standards a "D" grade. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce gave them a "C." And by 2006, the Utah Legislature was demanding a rewrite, fired up by a controversial effort in the Alpine School District to try a new approach to math.

New standards adopted in 2007 ultimately earned an "A-" from Fordham, but some unimpressed lawmakers threatened to pass a law changing them again.

Three years later, the state school board changed course, deciding the Common Core State Standards — an initiative of the National Governors Association — for math and for language arts were stronger.

This month, Utah is preparing to send parents their students' results from statewide tests aligned to the Core for the first time — news many expect will fuel debate over the controversial standards and how Utah teaches math. In some grades, preliminary results showed, 1 in 3 children is proficient.

Sen. Howard Stephenson, R-Draper, said the "jury is still out" on whether the Core is an improvement over the 2007 standards, which he opposed.

But parents shouldn't be alarmed by the low test scores, he said.

"I'm actually pleased by it because they're finally being honest about the level of proficiency," he said. "They had dumbed the scores down so low that they were actually claiming, with a straight face, that 90 percent of our students were proficient."

—

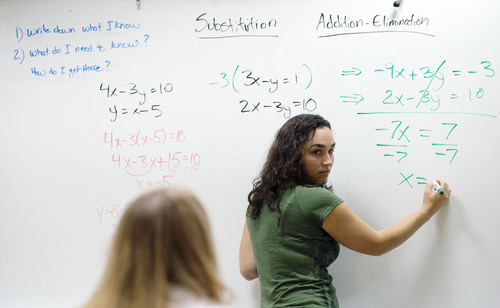

Teaching the new math • Ninth-graders at American Fork Junior High study geometric sequences, matrixes and vectors. Before the Common Core was adopted, they wouldn't have encountered these concepts until later in high school or during college.

"Students are thinking about things I never thought about until calculus or beyond," said their teacher, Travis Lemon, "and they're doing it in a very natural way."

The Core also de-emphasizes memorization, instead asking students to reason their way through a problem and be able to explain their answers.

The standards aim to increase the rigor of the American classroom, ensuring that high school graduates are prepared to enter colleges and the workforce. They establish when students should learn skills, but they are not curriculum.

Joleigh Honey, president-elect of the Utah Council of Teachers of Mathematics, said that as early as kindergarten, students are encouraged to think of the number 14 as not just 14, but also 10 plus 4.

In fourth grade, she said, students are expected to be as comfortable with fractions as they are with whole numbers.

"Students at a lot of grade levels really struggle with fractions, including our high school students," she said. "One of the things that our new Core does is, it starts the fraction conversation in really early grades."

Critics have accused the standards of being unnecessarily complicated, requiring students to take the long way to find otherwise simple answers. A particularly derided example asks students to perform basic addition and subtraction with a number line, using groups of hundreds, tens and ones to find the answer.

Honey said the intent is to help students understand the logic behind equations.

"We want that fluency to happen," she said. "But we don't want it to occur because students are memorizing six times eight is 48. We want them to have it because they've had enough time making sense and meaning of numbers since third grade."

—

Helping higher education? • The Alpine School District raised ire when it experimented with a similar strategy, using a math curriculum that de-emphasized memorization in favor of conceptual understanding. It was labeled as progressive by critics who moved their children into home-schooling or charter schools and lobbied for the creation of a splinter school district.

Brigham Young University math professor David Wright was a critic of what was dubbed "Alpine math," which the district backed away from in May 2006. In the aftermath, Wright helped write Utah's 2007 math standards.

He doesn't object to replacing them with the Core. What he does oppose, he said, is "the way the state Office of Education implemented the Common Core."

Teachers were not properly trained to make the transition, he said, and schools have struggled to find textbooks and other resources that are compatible with the new standards.

"The Common Core Math Standards are sound," he said. "They're not spectacular, they're not really any better than the old Utah standards, but the idea of working together so we can have national exams is a good idea."

The Core's designers, which included the Council of Chief State School Officers and education experts, sought to close the gap between high schools and higher education by starting with the needs of an incoming college freshman and working backwards through the grade levels to kindergarten.

That method could pay off in Utah, where higher education officials are urging high school students to better prepare for college by taking four years of math instead of the required three.

Utah claims the highest average ACT Exam score in the nation for states where all students take the test, but only 39 percent of Utah students met the college-readiness benchmark for math in 2014.

Over the last six years, an average of 25.3 percent of incoming freshmen at Utah Valley University have enrolled in remedial math courses, according to spokeswoman Melinda Colton.

At Salt Lake Community College, 12 percent of all students in fall 2013 enrolled in some form of developmental — or remedial — education, down slightly from 14 percent in fall 2011, according to school spokesman Joy Tlou.

"If I had a magic wand, the one thing I would change in higher ed," said Sen. Steve Urquhart, R-St. George, "would be to change public ed."

—

The standard debate • State school board member Debra Roberts agrees Utah has stumbled before and since adopting the Core in August 2010. Teachers have not had the resources, training or collaboration time for a smooth transition, she said.

"That's where we blew it and when I say 'we' I mean all of us," she said. "We blew it as a State Board, we blew it as a Legislature, we blew it as a state."

But Roberts emphasized that she believes the standards are better than those Utah educators wrote in the past or would have created instead of the Core.

"To reach out there and bring in some of these experts across the nation would have cost a great deal of money and obviously that's not something that we have in Utah," she said.

Honey, who helped draft the state's 2002 math standards, said the Core gave Utah the opportunity to use national expertise, make changes to fit local needs and arrive at a superior set of standards.

"I would say that we 100 percent benefitted from having the resources and information available from the national conversation," she said.

But not everyone sees it that way.

Oak Norton, an education advocate now affiliated with the group Utahns Against Common Core, led the opposition against Alpine math. He sees the Core as a nationalized version of those concepts.

But his primary criticism objection to the Core is not its content, but what he sees as a trend toward outside influence and away from local control.

"It's the same old stuff rehashed," he said. "They use buzzwords like 'critical thinking skills' to pass their agenda."

Norton said he would prefer to see districts set their own standards and provide only broad, generalized guidelines at the state level.

He also would support Utah adopting the standards used by California and Massachusetts in 2010, which he said were considered among the best in the nation. Both states have since adopted the Core.

Education officials point out they can and have made local changes to the Core, and deny Utah has yielded control of education. But Common Core opponents continue to view national standards as evidence of federal encroachment.

"Any time you nationalize anything, any program, you're going to centralize the power," Highland parent Renee Braddy said. "And when you centralize the power, you remove the voice of the teachers and the parents from being able to make educational decisions that are best for our students."

Local teachers and parents are capable of writing standards, she said. "I don't think using money as an excuse is necessarily a valid reason to basically give up our educational freedom," she said.

—

Here come the scores • The Utah Office of Education is finalizing scores from the new SAGE testing system and expects to deliver them later this month. This spring, the statewide tests reflected the Core academic standards in math and language arts for the first time.

State education officials are bracing for renewed backlash against the Core as Utahns realize fewer students are meeting grade-level expectations than in previous years.

But educators say the low scores are evidence of the Core's success, because the quality of teaching has not declined but the threshold for what is considered satisfactory has increased.

Given time, Lemon said, the standards will increase the ability of Utah children to compete with their national and international peers. And Honey said it would do more harm than good to jettison the Core in favor of another series of locally-produced standards.

"Students are reasoning and problem-solving now more than I have ever seen during my 21 years in education," she said, "and I really think it would be a tragedy to go backward."

Examining the Common Core

A group of Utah experts convened by Gov. Gary Herbert will meet for the first time Monday to begin evaluating the Common Core State Standards from a higher education perspective.

The standards describe the skills students should know in math and language arts in each grade to be ready for college and careers. Curriculum — or how the standards are taught — remain up to local schools and teachers.

The standards began as an initiative of the National Governors Association, and were developed with the Council of Chief State School Officers and education experts. States choose whether or not to adopt the standards.

Herbert also has asked the state attorney general to look into what, if any, federal entanglements have been involved in Utah's adoption of the standards.