This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2009, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In the mid-1990s, only about 40 percent of heart surgery patients nationally were going home with the right medications -- beta blockers, anticoagulants and other potentially lifesaving drugs. Intermountain Healthcare's numbers were better, but not by much.

So, in 1997, a research team at the Salt Lake City-based nonprofit health system developed a low-tech solution: a mandatory two-page checklist to help doctors ensure discharged patients get exactly what they need.

It was a simple innovation, yet one that yielded impressive results. Within a year, more than 90 percent of patients were getting appropriate medications.

Readmission rates at its hospitals went down. Survival rates went up.

Making evidence-based medicine easy to practice is Intermountain's modus operandi. Do that, its top managers and clinicians say, and health care gets better -- and cheaper.

It is a strategy that's not going unnoticed.

Last week, a team from the federal Office of Management and Budget visited Intermountain to explore why this health system is among those pioneering better health care.

President Barack Obama has repeatedly singled out Intermountain, along with the Mayo and Geisinger clinics and other so-called "organized practices," for delivering high-quality care at below-average costs. They are "islands of excellence in the sea of high cost mediocrity" as one Dartmouth report puts it; standouts in a country where cost and quality can vary wildly by geographic region.

Utah's total health care costs per capita are the lowest in the country. The state is efficient even by international standards, its costs ranking below countries such as Norway, Denmark and France. The U.S. overall, meanwhile, spends more than any other nation.

The state's young, healthy population doesn't explain it all, said Greg Poulsen, Intermountain's senior vice president: "It's also practice style."

If the Intermountains, Mayos and Geisingers can deliver this kind of health care, Obama has said, so should the rest of America. And the country could reap huge savings in health care costs if it did.

Using Intermountain as a benchmark, the 2008 Dartmouth report says, the nation could reduce health care spending on acute and chronic illnesses by as much as 40 percent.

The report also said Intermountain has driven down unnecessary "supply sensitive care" -- or care that tends to be provided because hospital beds, doctors and specialized equipment are abundant, rather than because a patient clearly needs it.

If all providers were to achieve Intermountain's level of efficiency in limiting such care, they would see an estimated 43 percent reduction in hospital spending, Dartmouth said.

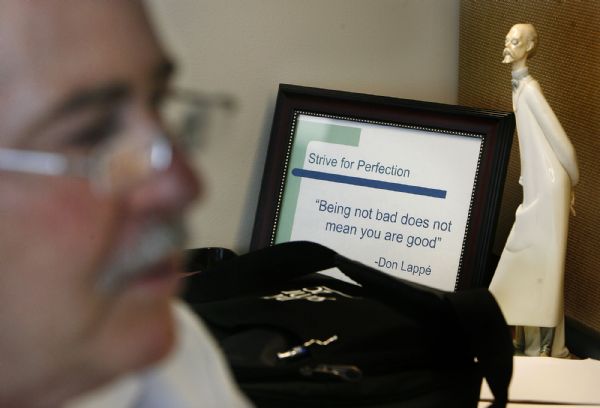

Donald Lappe, Intermountain Medical Center's chief of cardiology, said the health care system has "really engaged everyone -- physicians, nurses, administrators -- to an environment that is committed to best outcomes."

While some institutions "layer on" requirements from The Joint Commission -- an organization that accredits and certifies hospitals -- and others, he said, Intermountain has made them part of its mainstream care.

"When there is a right way, I believe our doctors -- to the best of their ability -- will deliver it the right way based on evidence-based medicine," said Lappe, who helped pioneer Intermountain's discharge protocol. "What we do as a cardiovascular clinical program is deliver tools that make it easier."

A new strategy » When Brent James started working for Intermountain in the 1980s, he discovered that the same variations seen in the delivery of health care across geographic regions could be found within a single health care system.

Patients treated by Intermountain for nearly identical conditions often left with similar results.

But what happened during their hospital stays was surprising: The "volume" of care each received could be dramatically different. Some received a plethora of tests and procedures; others, not that much.

"It turned out to be a common problem in medicine," said James, executive director of Intermountain's Institute for Healthcare Delivery Research and vice president of medical research.

It was about that same time that James came across statistician and professor W. Edwards Deming's theories of management. Deming, whose work revolutionized Japan's post-war industrial sector, believed costs go down as the quality of processes goes up.

The idea was a no-brainer for business, James said, but a radical concept for the medical community, which thought more meant better.

He decided to put the idea to the test as part of a 1987 Intermountain study on hospital-acquired infections. Starting antibiotics two hours before surgery, doctors discovered, reduced the infection rate to 0.4 percent from 1.8 percent over a year's time.

And it saved nearly $1 million in health care costs.

Getting HELP » Key to coordinating patient care, however, is the use of electronic medical records that routinely remind doctors and nurses of care guidelines, Poulsen said.

"We absolutely believe in best practices," he said, "and many of those are benefited by automation to make them work more consistently and effectively."

Built in the 1960s by cardiologist and medical informatics whiz Homer Warner, Intermountain's Health Evaluation Logical Processor (HELP) provides care guidance in 17 areas, ranging from diabetic care and blood ordering to acute respiratory distress-syndrome protocols.

What's more, it also codes data, allowing statisticians to conduct "reverse" clinical trials by examining historical trends in treatments and outcomes. This allows doctors to rely less on anecdotal evidence and more on hard science to determine what works -- and equally important, what doesn't.

The health system is now four years into a 10-year project with General Electric to develop a new health information technology program, called ECIS, which builds and expands on the strengths of Warner's technology.

"In most instances people are pushed in a gray area," Poulsen said, "and data makes gray areas less gray."

In 1999, for example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advised against giving healthy mothers the option of arranging early deliveries. By not electively inducing births before 39 weeks of pregnancy, it said, the likelihood of complications could be reduced. The college warned that pre-term babies were at higher risk for a host of problems, including severe respiratory-distress syndrome.

But doctors and nurses resisted the new guidelines. From their vantage point, it was hard to see a problematic pattern, according to an Intermountain study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology in April.

This made sense, considering that if an obstetrician performs 200 deliveries a year -- and 10 percent of his or her patients are electively delivered at 38 weeks -- statistics show only one baby would be admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) each year.

Better data, improved results » When Intermountain analyzed nearly 180,000 births, however, the data were startlingly clear: For babies born at 37 weeks, the incidence of severe respiratory-distress syndrome was 22.5 times higher than those born at 39 to 41 weeks. At 38 weeks, it was still 7.5 times higher. Other problems, such as pulmonary hypertension, admission to the NICU and hospital stays beyond five days, were also more likely.

"If no one ever gives you the scientific data to drive your decisions, you can be pretty comfortable not doing best practice. You just don't know," said Janie Wilson, operations director of Women and Newborn Clinical Programs, which in 2001 developed a program to curtail early-term deliveries.

Wilson's team met with OB-GYN departments and announced the intent to halt the practice. A patient-education brochure was created to explain the new policy. And an obstetric and delivery program, called StorkBytes, was programmed to capture data and trigger electronic alerts.

"It was very hard," said Wilson, who is also a registered nurse. "We found you really have to have physicians and nurses on the same page, and you have to make it easy to do the right thing."

Within six months of the initiative, however, the rate of early-elective deliveries at Intermountain hospitals dropped to 10 percent from 28 percent; eight years later, that number is less than 3 percent.

But something else happened, too: Intermountain lost money. By performing fewer early-term elective deliveries, the health system saw shorter lengths of stay. NICU admissions dropped. Patients received fewer lab tests, antibiotics and Caesarean-section surgeries.

"The bottom line to our cost was significant," Wilson said.

An analysis of the impact on the health system revealed it lost $3.3 million in net revenue between 2001 and 2005. And that was a conservative estimate, based only on length of stay in labor and delivery, Wilson said.

Sound science, lost revenue » It wasn't the first time this had happened.

Identifying and implementing best practices in a number of areas -- deep-wound infections, adverse drug events and community-acquired pneumonia, to name a few -- meant the health care system was hemorrhaging millions.

It created windfall savings for insurers, James said, "and we were struggling financially."

Being a nonprofit helps, he said. So does having a board of directors and an administration that is "mission driven."

But it also begs the question whether Intermountain's success can be replicated by other for-profit and nonprofit institutions.

Payment reform, Poulsen said, will have to happen first, so health systems aren't punished for providing more effective clinical care.

"The incentives today are wrong," he said. "You almost have to make a conscious decision that you will overlook what's in your financial best interest in order to do what's effective, efficient and appropriate ... [and] you know you're asking a lot of human nature to do that."

When that happens, the country won't just get more Intermountains, Mayos and Geisingers, James said.

"We'll get a level of health care delivery this country just hasn't seen before in terms of the quality of care we offer to patients," he said.

And, he added: "It will be at a reasonable price."

lrosetta@sltrib.com" Target="_BLANK">lrosetta@sltrib.com

Vertical integration » A health care system offering medical care and insurance coverage.

Range » 21 hospitals in Utah and southeast Idaho, as well as 140 clinics throughout Utah.

SelectHealth » An Intermountain company, it insures 410,000 -- about one-quarter of Utah's commercially insured.

Staffing » Employs 800 of Utah's 4,400 doctors.

Should Intermountain Healthcare be a model for health care reform? Share your personal experiences as a customer of the health care provider for possible publication in a future story by sending an e-mail to hcreform@sltrib.com">hcreform@sltrib.com. Please include your name and telephone number.