This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

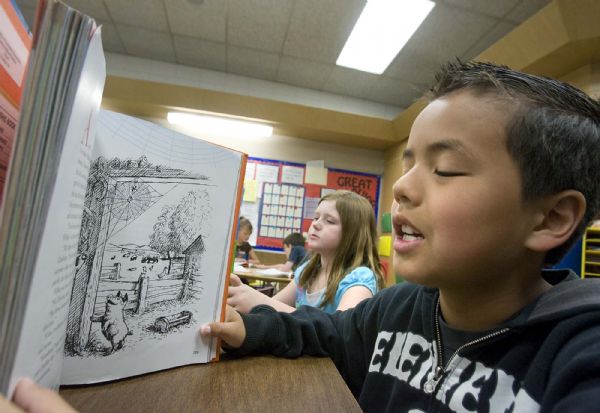

Murray » Geniah Stuber, a third-grader at Parkside Elementary, knows why it's important to learn to read.

"So then you can be, like, smarter," she said Tuesday during reading time in Mrs. Buehler's class.

Learning to read by the end of third grade also is a key predictor of children's future success, according to a new report released by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. But nationally and in Utah, two-thirds of students are not proficient readers when they start fourth grade, according to the 2009 National Assessment of Educational Process or NAEP.

"Up to third grade, children are learning to read," said Abel Ortiz, the foundation's director of evidence-based practices. "Starting in fourth grade, they are reading to learn. So if they don't learn to read by third grade, that greatly impacts their ability to learn in later years."

It also affects students' long-term earning potential, Ortiz said, and for low-income kids, their ability to leave poverty behind.

In 2009, 69 percent of Utah's fourth-graders scored below proficient on the national assessment, similar to the national rate of 68 percent. But in the Beehive State, students who are Latino, American Indian or Asian/Pacific Islander are falling behind their white peers at even higher rates than nationally.

The persistence of the "achievement gap," often attributed to differences in family incomes and first languages, is "profoundly disappointing to all of us who see school success and high school graduation as beacons in the battle against intergenerational poverty," wrote Leila Feister, the author of the report, "Early Warning! Why Reading by the End of Third Grade Matters."

The foundation study paints a much bleaker picture of reading proficiency in Utah than the state's numbers.

In 2008, only 23 percent -- compared with 69 percent in the 2009 NAEP -- of fourth-graders were not proficient in language arts, according to the Utah State Office of Education.

Reed Spencer, the state's K-12 literacy coordinator, said the state and national tests measure different things with different methods. For instance, NAEP surveys a representative sample, but the state test is administered to every student. The Utah exam measures students' knowledge of state curriculum, while NAEP measures literacy in a variety of ways.

"It's more difficult than any state assessment, not just ours," he said.

But he said reading levels in Utah are "solidly upward."

"Are we where we want to be? Of course not," he said. "We try to push the importance of literacy, especially early on."

To get all students reading at grade level by the end of third grade, the foundation report offered these recommendations:

» Improve health and education in early childhood, starting with healthy births.

» Encourage and enable parents and caregivers to be involved in children's educations. Families should read to and converse with their kids to help develop language skills.

» Use data-driven initiatives to transform low-performing schools into high-quality teaching and learning environments.

» Reduce the chronic absences and summertime learning loss that often contributes to the under-achievement of children from low-income families.

During the 2010 Legislature, Sen. Karen Morgan, D-Cottonwood Heights, pushed to require Utah schools to hold back students in first through third grades who are not reading on grade level. But lawmakers, worried the penalty was too stiff, passed a version of the bill that only requires schools to notify parents by midyear if their first-, second- or third-grader is reading below grade level. Schools also must tell those parents what interventions are available and give the students "appropriate reading remediation."

Also, Utah holds back fewer students than any other state, earning a No. 1 ranking in the Casey Foundation study. Only 2 percent of school-aged children in Utah have repeated one or more grades since starting kindergarten, according to the 2007 National Survey of Children's Health. The national average is 11 percent. The report did not link reading proficiency to the rate at which a state holds back students.

To improve kids' skills, Spencer suggests parents read regularly with their children, discussing any new words and asking kids to explain what the stories are about. Adults also should not shy away from using sophisticated language with kids, he said. That helps develop vocabulary and grammar skills.

Spencer also is a supporter of year-round school schedules to prevent the dreaded loss of learning that many students experience during the summer if they stop reading and studying.

"It would be great if, as a country, we could start shifting toward more learning friendly calendars," he said, "that don't necessarily add days to the school year but spread them out differently so the amount of consecutive time of not [learning] isn't so long."

Tribune reporter Lisa Schencker contributed to this story.

Study at oddswith state overreading skills

To read the "Early Warning!" report go to http://datacenter.kidscount.org/databook.