This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Craftsmen from a venerable Salt Lake-based company working with advanced sign-making technology a few years ago created a $10 million tower that shows crystal-clear images promoting the Wynn Las Vegas resort.

The structure features a 60,000-pound moving panel that clips along at up to 10 feet a second, changing the sign's images as it slides up and down high atop the 130-foot-tall design. When winds along the famous Strip hit 50 mph, specially crafted sensors halt the mobile panel in its tracks.

Then there's the hand-painted lettering on the door of the new O.C. Tanner jewelry store in Salt Lake City, the meticulous work last year of another sign-making craftsman.

Both projects, from the smallest to the largest, were created by Young Electric Sign Co., now celebrating its 90th year in the business.

"You want a cut-out vinyl sticker for your front door? We'll do it," said Jeff Young, the third-generation head of YESCO's Salt Lake City operations. "That might cost $100. Even our largest customers need small signs."

And if you want something a bit more sophisticated -- the Wynn sign is "the most technical sign we are aware of," he said -- YESCO will do that, too.

A third-generation family affair, YESCO was founded in 1920 by English immigrant Thomas Young Sr. Grandson Jeff runs the 124-employee, $20 million manufacturing division in Salt Lake City. Brother Paul is executive vice president and brother Mike is president. Dad Thomas Jr., now 82, presides as chairman of the company, which has operations in 10 states and employs nearly 1,500.

YESCO has been involved in the creation of some of Utah's most iconic signs -- the Snelgrove ice-cream cone, the Deeburger clown and the Key Bank Tower. In Nevada there are Wendover Will and Vegas Vic.

The multigenerational workplace goes far beyond Thomas Sr.'s progeny. At least one-third of the Salt Lake City work force is made up either of second- or third-generation employees or of various members of the same families.

One "engineer is third generation. The woman who handed papers to me as I walked down the stairs just now is third generation," said Jeff Young. "We have husbands and wives, fathers and sons." Metal fabricator Mike Peck recently retired after 55 years, following in the footsteps of father Glenn, a production manager who retired after 48 years.

--

Family ties » The uniqueness of the industry drives family connections in the sign business, Young said.

"Once someone gets here, they tend to stay." The skills in many ways are distinctive, making them difficult to transfer.

For example, neon signs have been a mainstay for all of YESCO's 90 years. First used in signs in 1910 in Paris, the technology was imported to the United States in the early 1920s. Thomas Sr., who founded the company in Ogden, eventually obtained a license for its use and was the first in the Intermountain West "to provide neon for customers," said Jeff Young.

Before that, electric signs were made up of lots of light bulbs, while others were lit by natural gas.

Neon-sign craftsmen labor for years learning the art of bending glass tubes into myriad shapes. Jeff Young said it takes three to four years "to be good enough." He employs three in Salt Lake City, while companywide YESCO has 20.

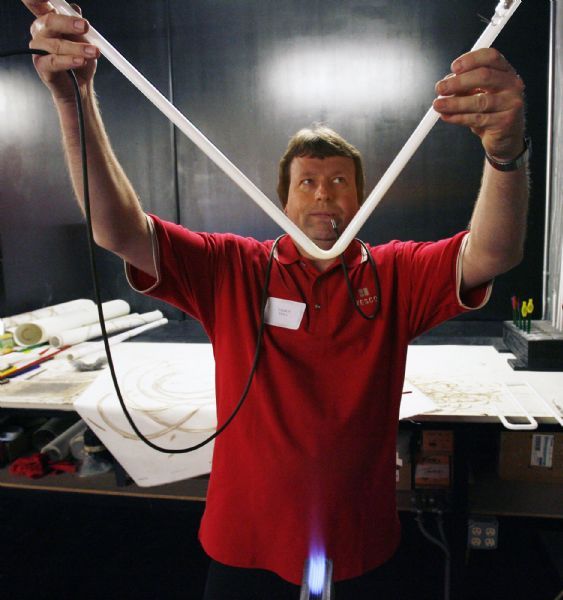

One of his neon experts is Talbot Hall, a second-generation YESCO employee in his 27th year with the company.

"The art of glass bending hasn't changed in the time I've been here," Hall said from his shop on the second level of YESCO's new cavernous assembly plant just west of Bangerter Highway at about 1600 South. "The electrodes on the ends of the tubes may have advanced a bit, and different colors have been introduced, [but] that's about it.

Still, "I'm always refining my skills," said the 45-year-old Lehi resident who, at age 18, followed his stepfather to YESCO. He worked at various tasks for 10 years before starting to bend glass. "It takes six years to become a journeyman."

--

New technology » Eighty percent of signs YESCO manufactures are illuminated, with neon used in a third of them, according to Jeff Young. But the company also spends a lot of time creating signs that speak to the 21st century, in digital formats and with giant screens as advanced as any HD television.

Tom Young Jr., who started in his dad's company at age 14 sweeping floors, is nostalgic for long-ago days when neon signs blanketed downtowns, "making the city feel alive" before many zoning laws banned overhanging and flashing signs. But he finds his company's advancement into the digital world using light-emitting diode (LED) technology "exciting."

"We just sort of stumbled into that technology," he said. "Customers tell us that when they see that, they don't want to look at anything else. It's full of color and life and action and brightness." The Wynn Las Vegas sign is at the extreme end of that technology.

A few years ago, after an LED sign was installed at an auto dealership alongside Interstate 15 in Davis County, its brightness had to be toned down because of complaints from passing motorists. Similarly, Tom Jr. remembers testing a larger sign along Interstate 10 in the Phoenix suburb of Chandler.

"It was allowed to run all night, and pilots landing at the Phoenix airport were calling the tower wanting to know what that bright light was."

Even though that one had to be dialed down, too, "such signs have tremendous potential; they are phenomenal."

Lori Anderson, president of the Virginia-based International Sign Association, said technical advances makes this "an exciting time to be in the signage and visual communications industry. The technology just continues to grow."

Like Jeff Young, who speaks warmly of the craftsmen he employs, Anderson said sign making is "more than simply a manufacturing industry, it's an art form," taking raw materials and forming them into shapes and colors that transmit messages to viewers.

She praises YESCO, one of the nation's largest sign makers, as being "true innovators. They are real leaders in an industry ... that the general person walking down the street takes for granted."

Young Electric Sign Co. has 31 offices in 10 states, including seven in Utah. YESCO employs 1,497 in the state, though its Las Vegas Division is the largest, with 384 employees.

The family of Thomas Young Sr., English immigrants, settled in Ogden in 1910 when he was 15. He went to work in 1916 for the Electric Sign Service.

In 1920 and with $300, Tom Young started his own company, Thomas Young Signs, later changing the name to Young Electric Sign Co. The company expanded into surrounding states, including Nevada. The first electric sign he sold there was in 1932, to the Oasis Cafe on Fremont Street in Las Vegas.

The headquarters moved to Social Hall Avenue in Salt Lake City in 1937, then to 300 West in 1949 where it was for 60 years. Thomas Sr. died in 1971 at age 76. YESCO moved farther west in 2009 -- to 1605 S. Gramercy Road (about 4200 West) -- into a 103,480-square-foot facility.

A gas that is extracted from the air we breathe, it's colorless under standard conditions, but gives a distinct reddish-orange glow when charged electrically in advertising signs. Other colors are created by lining the inside of those tubes with special phosphors.