This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

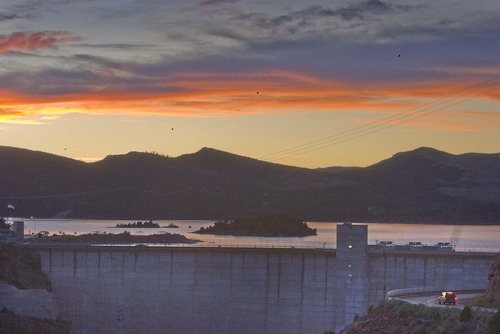

Flaming Gorge Dam • It is not New York or Los Angeles, but it has still received millions of dollars for security.

It is not a nuclear power plant or airport, but it is considered a critical piece of infrastructure. It is not a military base, but it has 24-hour police protection, security cameras, motion sensors and this winter it will receive a hovercraft to patrol and defend it by land and water.

It is Flaming Gorge Dam, in the corner of Utah that meets Wyoming and Colorado. In a policy that has mirrored more high-profile locations around the country, the federal government has spent millions of dollars since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks protecting a dam on the Green River best known for some of the finest trout fishing in the world.

The Bureau of Reclamation has paid the Daggett County Sheriff's Office $4.77 million since 2002 for police protection at the dam, with a new contract between the bureau and the county to be signed this fall. There have been one-time costs, too. The bureau has bought everything from the cameras and sensors to the buoys that keep boats from approaching the dam to hybrid SUVs driven by Daggett County deputies.

Other federal agencies have contributed, too. The FBI helped coordinate anti-terrorism drills at the dam in 2003 and 2009. Daggett County is using a $100,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to purchase the hovercraft.

"It was extremely important to secure these facilities even if they're in remote locations because the remoteness doesn't mean they aren't accessible and the impacts they have are tremendous," said Larry Todd, a retired deputy commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation.

It is unclear just who or what is menacing the dam. Neither documents The Salt Lake Tribune obtained through the Freedom of Information Act nor interviews with state and federal authorities identified a specific threat against the dam since 9/11.

Just reaching Flaming Gorge Dam requires an effort. It's a 3 ½ hour drive from Salt Lake City. Only one road, U.S. Highway 191, goes in and out of the dam. From the right spot in Wyoming, the dam is just as accessible by boat as by car.

"We haven't had any specific threats that I'm aware of, and that's good," said Steve Hulet, the manager at Flaming Gorge Dam. "That's why we have security. Security is working."

Richard Volpe, a special agent with the Bureau of Reclamation who also is part of Utah's Joint Terrorism Task Force, points to the February arrest of a Saudi national living in Lubbock, Texas. The FBI has said the man was trying to buy ingredients for explosives and had a list of targets that included several dams and reservoirs in Colorado and California.

"The tangible thing you get out of security is nothing happens," said Volpe. "Nothing happens and people ask why you're spending all this money."

Azamat Sakie, an assistant lecturer at the University of Wyoming who studies comparative politics and terrorism issues, finds a low likelihood of an attack against Flaming Gorge Dam.

"Padding the security is a natural reaction [to 9/11] and should be done," Sakie said, "but overspending is not useful."

Sakie said some money might be better spent on maintenance to ensure a mechanical or structural problem doesn't cause the dam to breach. Also, Sakie points to a recent article by one of his colleagues saying instilling a fear equals a success for terrorists.

"By overdoing the security in certain cases, we actually give in to their goals," Sakie said.

—

Al-Qaida worries • After shooting and killing civilians in the visitor center, the terrorists entered the interior of the dam and seized control of its workers and the millions of gallons of water which pour through it.

Then the real scare: The terrorists tethered a bomb and suspended it over the side of Flaming Gorge Dam facing the 3.7-million-acre-foot lake.

Of course, the terrorists weren't terrorists but actors in a security drill held at the dam on June 2, 2003. SWAT teams with the FBI and other law enforcement agencies had to regain control of the dam while paramedics treated the victims. A similar drill was held May 6, 2009.

The drills reflected just one of the scenarios envisioned by security experts, said Larry Todd, who before his retirement from the Bureau of Reclamation in 2008 oversaw security at dams.

Bureau of Reclamation dams had only basic protections before 9/11. Todd said there was one security officer in Denver for all of the bureau's dams. At Flaming Gorge Dam, visitors used to be able to walk unescorted along US 191, park their car on the curb beside the visitor center or dock their boat just feet from the visitor center's door.

Today, pedestrian traffic on the highway near the dam is prohibited, barriers keep cars about 30 paces from the visitor center and buoys prevent boats from approaching the dam. The visitor center dock has gone unused for almost 10 years and this summer it was submerged in water. Visitors can still go on a tour, but they are subject to a search.

After the terrorist attacks in New York, Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania, al-Qaida "was the big thing" concerning the bureau, Todd said, but the bureau soon identified other types of terrorists that concerned it.

The bureau underwent what Todd considers a thorough process of identifying security liabilities at its dams, as well as the potential for damage downstream if a dam were to be attacked.

"We really became concerned about the potential for a lot of different kinds of disabling; how an attack may not just disable but what kind of impacts those would have," Todd said. "Could there be flooding downstream? Could there be economic impacts? Power impacts?"

Besides retaining water that will eventually be used for irrigation and industrial and culinary uses, Flaming Gorge Dam generates electricity for communities as far away as Nebraska.

The most significant security episode for the dam in the last decade happened 3 miles away at a Bureau of Reclamation warehouse in Dutch John.

In November 2004, a bureau employee found telephone lines and communication lines were cut outside the warehouse. Reports from the Daggett County Sheriff's Office and the FBI refer to the damage as vandalism, but the FBI categorized the episode as an act of domestic terrorism.

Plaster casts were made of the tire tracks found outside the warehouse, according to documents obtained by The Tribune. Agents measured the width between the tracks to determine what model vehicle made them. Old soda bottles and beer cans found in the vicinity were collected as evidence.

Then a sheriff's deputy mentioned that a Dutch John resident had lost his job at the dam under what the documents describe as "unfavorable circumstances." The man in 2006 pleaded guilty in federal court to a felony count of damaging communication lines or systems. A judge ordered him to serve 36 months of probation and pay $1,566 in restitution.

—

Impacted communities • So what would happen if Flaming Gorge Dam were to be breached?

"I don't think anybody really knows," says Daggett County Sheriff Jerry Jorgensen.

Jorgensen assumes all the water would have to escape the dam at once in order to inflict a true catastrophe downstream.

But Todd said a lesser event could cause big trouble to both the power grid and downstream communities. Flaming Gorge Dam is part of the intricately managed Colorado River system. Excess water into the system would force action by other dams and reclamation systems all the way to the Mexican border, Todd said.

If too much water spewed from Flaming Gorge Dam, or errors were made downstream, "communities can be absolutely impacted and flooded and so forth," Todd said, "and I don't know by how much, and I couldn't say which ones."

Rick Scott, manager of security and dam safety for the Bureau of Reclamation's Upper Colorado Region, said the bureau has calculated the likelihood of a failure at Flaming Gorge Dam from events like erosion or an earthquake, but there isn't enough data to predict the likelihood of destruction due to a terrorist strike.

"With terrorism, you know it's out there, but you can't put a probability on it like you can with failure modes," Scott said.

The Bureau of Reclamation and other government agencies have removed reports and maps discussing such scenarios from their websites since 9/11. One report, which can still be found on the Internet, is a 1998 Bureau of Reclamation study about how a failure of Flaming Gorge Dam would impact Glen Canyon Dam 490 miles away in Page, Ariz. That study assumed Flaming Gorge Dam would fail by water overtopping it, not by a terrorist attack.

But if Flaming Gorge Dam did fail, the report said, the water would rush as far as Lake Powell and into Glen Canyon Dam. Water would overtop Glen Canyon Dam by almost 3 feet, the report said. However, the report said it was "unlikely" that would be enough to cause a failure.

Breaching the concrete-constructed Flaming Gorge Dam, however, would require a tremendous effort. According to figures found on the dam's website, the dam is 27 feet thick at its crest. The dam thickens as it descends, reaching 131 feet at its base.

—

Local benefits • Jorgensen, a former warden at the Gunnison prison who became Daggett County's sheriff this year, points out that nearly every county in the United States has received federal homeland security money to buy things it couldn't otherwise afford. In Utah, most counties received money to buy motor homes or camping trailers that serve as command stations during emergencies. Jorgensen used his county's federally purchased mobile command center last month to coordinate the successful search for a Boy Scout who disappeared in Ashley National Forest.

While the $4.77 million the Bureau of Reclamation has paid for police protection may not be much in the grand scheme of the federal government, it's a lot in Daggett County.

The county has about 950 residents. The average worker in Daggett County earned $2,300 a month in 2010 — about two-thirds of the average pay in Salt Lake County, according to the Utah Department of Workforce Services.

Jorgensen uses the federal money to pay wages and overtime to deputies to guard the dam, to pay a few part-time deputies or off-duty police officers from adjacent counties to work some of the shifts, and to pay for vehicle and fuel costs.

Two peace officers are on the dam at all times, often with one on the west side and one on the east.

On a recent August night, Daggett County sheriff's Deputy Layne Ferrin walked around the exterior of the visitor center, ensuring the doors and gates were locked. He also looked for pieces of luggage left behind. A suitcase could be filled with explosives, he warned.

From his hybrid SUV, Ferrin also watches any truck which passes on US 191. He makes sure none of them stops at the dam, but he also is watching that none stops on the Cart Creek Bridge a quarter-mile west of the dam. Ferrin worries a truck bomb could destroy the bridge to isolate the dam in a prelude to an attack.

"You and I don't think that way," Ferrin said. "Terrorists do."

The deputies also have stopped a few drunken drivers at the dam and responded to other circumstances that arrive. Daggett County Chief Deputy Chris Collett said a few months ago a man in the midst of a heart attack stopped at the dam. Deputies helped save him, Collett said.

"This has turned into a central location where people know they can go if they have a problem," Collett said.

Tamara Twitchell, the Daggett County emergency manager, said the county pursued the hovercraft after the 2009 anti-terrorism drill at the dam. Ice, snow and waves prevented a conventional boat from reaching the dam on the lake side to evacuate people on top of the dam, Twitchell said. It was determined a hovercraft would be effective at retrieving people and patrolling the lake side of the dam for explosives planted on or below the water surface.

But Twitchell said the county mostly plans to use the hovercraft during ice fishing season. The county over the years has had anglers on Flaming Gorge Reservoir fall through the ice or get stranded on ice sheets that have broken loose. A hovercraft will work better in winter conditions than a conventional boat, Twitchell said.

"I think it's pretty well what we need here," Twitchell said. "We aren't in an area that feels threatening, but we don't want to let our guard down because that's usually when you get hit."

ncarlisle@sltrib.comTwitter: @natecarlisle ===—

About the dam

• Construction of Flaming Gorge Dam began in 1958. Lady Bird Johnson dedicated it in 1964.

• It was built as part of the Colorado River Storage Project, which sought to equitably divvy water among Colorado River states. The dam's power plant provides electricity to Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nebraska and Nevada.

• The dam had 53,212 visitors in 2010.