This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Frustrated by a lack of rape prosecutions, West Valley police Detective Justin Boardman is developing a new way to investigate sexual assaults based on recent research surrounding the neurobiology of trauma.

Important to a successful investigation is understanding the impact of trauma on a rape victim, Boardman says, pointing to studies by a Michigan State University researcher. They explain why a victim's story could be inconsistent and even incoherent — and why, after undergoing an invasive exam seeking forensic evidence, a victim would drop the case.

"A soup of hormones," including opiates, cortisol and oxytocin, released at the time of an attack can disrupt the victim's consolidation of memory temporarily, according to psychology professor Rebecca Campbell's examination of the neurobiology of rape trauma. Victims can provide "fragmented and sketchy" statements that investigators often discard as not credible.

Pressed for more details, the victim can experience a "secondary victimization," Campbell says in an interview. They feel "blamed, depressed and anxious." When the victim realizes police don't believe her, she disengages from the investigation — case closed.

A victim should be afforded time — about two sleep cycles — before any in-depth questioning by detectives, according to Campbell. And investigators should show empathy and not question the victim as they would a criminal suspect with challenges, such as, "You are making this up."

Campbell's research is "life changing," Boardman says.

"I was going, 'Oh, my God, I've been doing this wrong all this time,' " he says of the traditional approach to questioning a rape victim. "That was frustrating because we don't go to work every day to do a bad job."

The West Valley City Police Department is in the initial phases of adopting a process similar to that suggested by Campbell, Boardman says. It has led the department to develop a new protocol for questioning rape victims that already is increasing the number of cases being filed for prosecution.

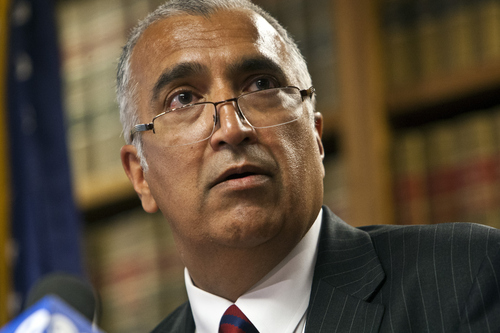

Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill says Campbell's work in rape trauma is groundbreaking. It outlines an approach similar to that taken with victims of child sex abuse, he says.

"This emphatically addresses what the victim's needs are before we press for arrest or prosecution," he says. "Why we haven't applied it to adult victims boggles the mind."

Gill proposes a "multidisciplinary team" approach in which police, prosecutors and health-care professionals work together to seek better outcomes.

Key to that, he says, is uniformity in training that is based in science and focused on the victim.

Such changes, however, are not easy, the D.A. concedes. "The biggest challenge we have is the complacency of our institutional biases. We get comfortable with our practices and that becomes our reality."

"We have to move away from the old model," he says. "This will require buy-in at all levels."

—

Rape-kit controversy • Rape investigations in Salt Lake City grabbed headlines in April when it came to light that hundreds of rape kits — forensic evidence that may include DNA — had been shelved by the police department without processing. Among the reasons for the backlog: Victims declined to go forward with prosecution.

The phenomenon is not unique to Salt Lake City and, in fact, is common across the country, according to victim advocates and law-enforcement officials.

At an April 15 City Council meeting, Councilman Kyle LaMalfa asked Police Chief Chris Burbank why his department had not analyzed 788 of 1,001 such kits collected between 2003 and 2011. The councilman pointed to a study of Salt Lake County rape cases by Brigham Young University researchers Alyssa Lark and Julie Valentine. According to their analysis, only 9 percent of all rapes reported countywide resulted in criminal charges.

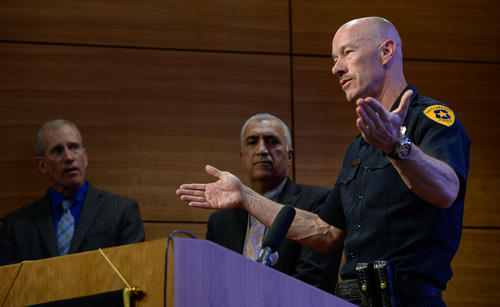

Burbank told the City Council that his department aggressively investigates all rape allegations. "Our investigators are very passionate about solving these crimes."

But, he added, there are good reasons why not all rape kits are analyzed, including when the alleged perpetrator already has been identified. And, he added, it costs about $1,100 to process each kit.

After the contentious council meeting, the chief initiated the "Code R Project" in which Salt Lake City cases are posted online to explain why rape kits had not been sent to the state crime lab. The cases list no names or real case numbers to protect victims.

Of the 20 posted so far, a fourth to a third — depending on interpretation of the online information — say the rape kit was not processed because victims declined to prosecute.

—

Complex cases • Campbell's research and the Salt Lake City backlog indicate that Salt Lake City police officers have not been trained to recognize impacts of rape trauma, LaMalfa says.

"What problem are we trying to solve here?" he asks. "We have been focusing on rape kits. But the data behind the rape kits reveals a harder problem to deal with."

According to Campbell, it is important for all police officers to be trained in rape trauma because a victim's initial contact with law enforcement most likely will be a patrol officer.

"Every contact with a victim is a chance to help or to hurt," she says. "If the first responder doesn't recognize trauma, it could shut it down right there."

As in most law-enforcement agencies, Salt Lake City police officers are not trained specifically in rape trauma, says Deputy Chief Terry Fritz. But the department is open to new information, training and investigative techniques.

"I would welcome the [victim-trauma] training," he says. "The more proficient we become at recognizing these types of behavior the better we perform."

Fritz says officers in the department recognize that trauma comes with most crimes, including nonviolent ones such as burglary. That is why, he explains, detectives re-interview victims three to six days after any crime, including sex crimes.

Rape is especially difficult because so many factors — including culture — come into play.

Fritz allows that some victims may not want to prosecute, believing police and prosecutors aren't on their side. But, he adds, there may be other reasons, including disgrace in the eyes of family and church members.

And the victim may fear testifying in open court where defense attorneys could seek to undermine her credibility, he says.

"They may want to move on," Fritz says, "rather than have this dragged out."

—

Long-term impact • Campbell's research can be helpful to victims in a number of ways, says Holly Mullen, executive director of the Rape Recovery Center in Salt Lake City. The neurobiological analysis reveals that hormones called corticosteroids released during a rape can immobilize a victim so she cannot fight or run. This "tonic immobility" adds "freeze" to the traditional "fight or flight" scenarios.

"When they come to us, they are filled with so much self-induced blame," she says. "We spend a lot of time working back from there."

The realization, Mullen says, that biologically they could not have done more to escape or fight off a perpetrator can give them some solace.

Mullen applauds Boardman and the West Valley police for adopting a progressive approach to rape victims. But, she laments, the treatment of rape victims, for the most part, remains troubling.

"I don't know why rape victims aren't afforded the same respect as victims of other crimes," she says. "It's important that more law enforcement and prosecutors see [Campbell's] information."