This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2009, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Eons after hulking dinosaurs thundered around central Utah, a young paleontogist spent years on his belly teasing their fossilized bones from rock so he could help tell the world the story of life on Earth.

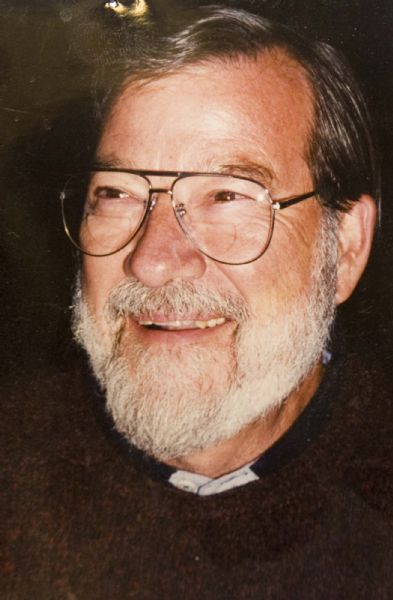

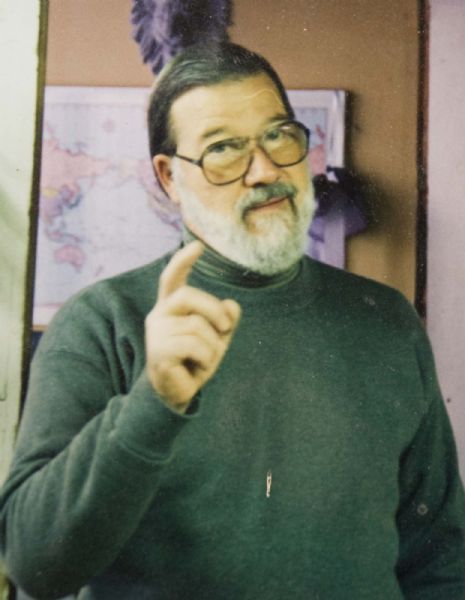

Jim Madsen went on to be the first-ever state paleontologist -- in Utah or anywhere else. He trained scores of young scientists how to understand dinosaurs and published cornerstone research in the field of paleontology. He helped establish Utah as a mecca for the study of Allosaurus and other ancient meat-eaters.

Madsen died Saturday at age 77.

"His heart was always in the science," said his daughter Lisa Madsen, who, along with her brother, Chris, and four grandchildren survive the famed scientist.

"Jim was really the guy to go to," said Dan Chure, paleontologist for the Dinosaur National Monument in eastern Utah. "He knew more about this than anyone else."

For Chure, a Columbia University graduate student back in the 1970s, meeting Madsen was like meeting a giant in the field. Madsen had just published his monograph on Allosaurus fragilis that remains a standard text.

"It has to be one of the most frequently used dinosaur papers in paleontological literature," said Chure.

The legendary Utah geologist William Lee Stokes chose Madsen in 1960 to oversee the excavation of the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry, which held bones of creatures that dominated the area around Price about 150 million years ago. More than 14,000 fossils came out of it all of them painstakingly released from the Utah redrock, sometimes by instruments as delicate as dental picks and many of them still being used to decode the planet's geological story.

Madsen was elected in 1998 to be an honorary member of the international Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. In addition, an Allosaurus species from a time before A. fragilis roamed Utah is in the process of being named for him, A. jimmadseni.

"In a way," said Chure, speaking about a paleontologist's work, "we speak for the dead."

In his later years, Madsen and his wife, Sue, oversaw a small menagerie of Dalmatian dogs, ducks, geese, honeybees and a community garden in the ravine behind the home where he'd been raised in East Millcreek. Sue died in 2002.

Madsen and his children expanded his paleontological work through Dinolab, a business that designed and built dinosaur exhibits for natural history museums worldwide.

Those who knew Madsen described a man of unusual humility and warmth, generous with the scientific treasures he had discovered with students and colleagues around the world.

One time, Chure remembers Madsen taking him into the basement to share a rare brain case. "You ought to see this specimen," Chure remembers his mentor and friend saying. The two went on to publish a significant paper on the find.

Brigham Young University paleontologist Brooks Britt recalled how Madsen would "make up" the name of a prize and send checks to young researchers. It was this way "he funded research out of his own pockets."

"He wasn't out for the publicity," Britt recalled. "He was in it for the science and in it for Utah. And he was always enthusiastic."

After the U. shuttered its paleontology program, the state Legislature created a position in 1977 to manage the Cleveland-Lloyd collection. Madsen took the job and oversaw continued research through the Utah Geological Survey for a decade.

In that role, said current State Paleontologist Jim Kirkland, Madsen began several pioneering initiatives. One was to establish a bibliography of Utah paleontology. He also promoted protection of paleontological resources, resisting a push to sell off key sites on state lands.

But it wasn't until March when President Barack Obama signed the Paleontological Resource Protection Act, that the idea fully took hold as federal law.

"A lot of this stuff got traction from Jim Madsen," said Kirkland.

Kirkland has consulted Madsen over the years. He even saw the sage paleontologist Madsen at a professional meeting last year, after his health had begun to fail.

"Until he died," Kirkland said, "he was a driving force in paleontology."