This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Prison populations around the country have been in steady decline for the past 10 years.

In Utah, it's a different story.

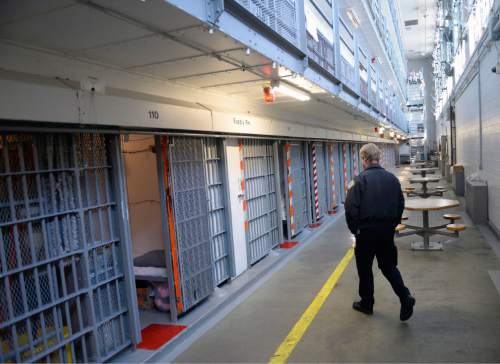

The number of men and women in the state's prison system has continued to rise, with the highest drivers being nonviolent criminals and sex offenders, who are staying in longer and taking up more beds than ever before, according to data collected by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Sex offenders now take up 42 percent more beds than they did 10 years ago, making them the largest group inside the Utah State Prison.

It's a fact that is coming under scrutiny as state lawmakers and public safety officials search for ways to improve the system, get the prison population under control and stop the "revolving door" in which so many offenders seem to get caught.

Sex offenses and how the state deals with them, in particular, have raised tough question about how Utah handles these crimes, whether offenders are getting adequate treatment and at what point they are being released back into the community.

A third of all prisoners in the state prison system are in for sex crimes, according to Pew data. And that number's going up, Board of Pardons and Parole member Clark Harms said recently.

At the rate Utah is going, Harms said, the state's prisons may soon become a holding facility exclusively for killers and sex offenders.

They simply won't have room for anyone else.

"If that's where we want to be," Harms told a Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice sentencing subgroup, "fine."

While subcommittee members — lawmakers, lawyers and judges — seemed interested in addressing the issue, perhaps by crafting recommendations to overhaul the way Utah treats these offenders, the issue is wrought with political pitfalls and tough questions.

Are Utah's harsh sentences necessary to keep the community safe? Or are they placing an undue burden on the state's ballooning prison system?

The subcommittee is unlikely to tackle these questions before the Legislature reconvenes in January, choosing instead to set its sights on less complicated, and less politically charged, issues.

But sex offenders can't stay on the back burner forever, Harms warned.

"I'm not saying that we ought not to punish," Harms said. "But I'm saying that [sentences of] 25 to life, or even a presumption of 15 years to life on regular first-degree felony sex offenses, you're going to have to, eventually, the board is going to get to a point where we have to start letting everyone else out because all we have room for are murderers and sex offenders."

—

Accelerated growth • It's no coincidence that there are more sex offenders today than ever before in Utah's prison system.

It's calculated.

And it's likely to speed up in coming years.

That's because, in 2012, lawmakers passed a 25-years-to-life mandatory sentence for child rape. This, along with enhancements that boost the penalties in other sex offenses, has driven up the numbers and solidified the image that Utah is tough on child predators.

According to data collected, the two top crimes for which people are incarcerated in Utah are aggravated sexual abuse of a child and sexual abuse of a child. Both are first-degree felonies. Both carry the penalty of six-, 10- or 15-years-to-life.

Since 2004, both crimes have seen marked growth: 87 percent and 21 percent, respectively.

The state won't likely see, or know, the impact of these lengthened sentences for several years — anyone convicted under the new, stricter guidelines wouldn't be up for parole until at least 2027. By then, hundreds of more sex offenders will have been sentenced.

—

Treatment • The problem, criminal-justice experts warned, is that locking these offenders up for at least 25 years often leaves them ill-equipped to re-enter society when the time comes.

And the more offenders being sentenced to such steep penalties, Salt Lake City-based defense attorney Mark Moffat said at a recent sentencing subgroup meeting, the more strain on prison resources that haven't been beefed up to accommodate the rising influx of sex offenders.

"Our statutory scheme makes it so that sex offenders go to prison," Moffat said. "And they end up serving just a ton of time where we have an excellent prison-based sex-offender treatment program that works in its ability to combat recidivism, but there's been no funding for that for years."

Of all types of criminals sent to prison, sex offenders are the most likely to be first-time offenders, meaning they have no criminal record. According to Pew data, 78 percent of sex offenders locked up in Utah's prisons had no prior convictions.

National and local studies have shown that treatment reduces the likelihood that sex offenders will reoffend and wind up back behind bars.

One Utah analysis of inmates who successfully completed treatment programs showed that about 20 percent of those offenders returned to prison within one year of their release — as opposed to 42 percent of those who did not complete a treatment program.

In both groups, the study noted, the offenders who were returned to prison largely committed parole violations rather than new crimes.

According to a 2003 report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, sex offenders were found to be less likely than non-sex offenders to be rearrested for any crime after their release. About 5 percent of all sex offenders were arrested for another sex crime within three years of being released, the report stated. For child molesters, that number was even lower: about 3 percent.

But Utah's $1 million annual budget for treating incarcerated sex offenders hasn't increased since 1996.

The 18-month treatment program has a limited number of seats. Offenders are often wait-listed and, in some cases, may be kept in prison longer so they can complete treatment.

"That's been a constant, really, for every public hearing and in the more targeted hearings with prosecutors and victims' advocates, prisoner advocates, everyone," CCJJ Executive Director Ron Gordon said and in an interview. "They're all advocating for increased treatment opportunities."

—

Politics • The state's handling of sex offenders came under fire at a recent meeting of the sentencing subgroup — an assembly of lawyers, public safety officials and legislators charged with making recommendations to policymakers on how to drive down the prison population and address the "revolving door" cycle of the criminal-justice system.

But when Len Engel, from Pew, asked the group members if sex offenders should be a priority in their legislative push, the assembled men and women balked.

"Although it is one of our most significant drivers, it's also one which is very policy driven," said Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill, who sits on the subgroup.

"I would push that off to the back for right now. It's worthy of us approaching, but we need to approach it in intelligent ways."

Politically, Gordon said, it's a difficult issue to broach — and that has not been lost on those charged with crafting policy recommendations.

Lawmakers who just two years ago passed legislation to crack down on child sex abuse are unlikely to backpedal so quickly — especially in an election year.

The subgroup concluded that the easiest issue to address with regard to sex offenders is treatment.

"We only have a few months to put together a package of recommendations, so we have a limited amount of time to focus on what we want to focus on," Gordon said.

"That's part of the approach that the commission has taken. Where are we going to get the [furthest] in the time we have?"

Gordon noted that other issues — like those related to sentencing guidelines and sex offenders' prison population growth — are likely to still come up, just perhaps not in the first round of recommendations.

"It's a difficult policy area, and one that everyone seems to have some type of opinion on and thought on," he said. "As we approach that population of offenders, I hope our approach would be the same as with all other populations. There are a number of different considerations that have to take place, and I hope we don't shy away from any of them just because it might be tough.

"There's an interesting and unique balance: being responsive to the public, mindful of keeping risk levels down, but also trying to figure out how we can help these populations."

mlang@sltrib.com Twitter: @Marissa_Jae