This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On Aug. 4, an attorney representing the United Effort Plan, the polygamous trust controlled by the state of Utah, had to review an agreement to sell some of the trust's property. It took the lawyer 45 minutes and the lawyer billed the trust $60.

Also that day, another lawyer representing the trust had to review filings in a lawsuit where a former child bride is suing the UEP. That took three hours and the attorney billed the trust $780.

The same day, according to bills submitted by the trust, a third attorney spent five hours and 45 minutes on UEP business, including reviewing some of the aforementioned court filings, talking with a Salt Lake Tribune reporter who requested an interview, having a discussion about how the prostitution case surrounding UEP fiduciary Bruce Wisan impacted the trust and sending an email to a fourth attorney employed by the trust. That lawyer billed the trust $2,156.25.

Before the day ended, two more lawyers worked for the UEP for a total of eight hours, according to the billings.

In all, Aug. 4 cost the UEP — which owns most of the property in Hildale, Utah, and Colorado City, Ariz., plus properties in Bountiful, British Columbia — $5,396.25 in attorney fees.

Or at least it has, so far. In its filings with the judge overseeing the UEP case, the trust says some of its lawyers have not yet submitted invoices for that time frame.

The UEP is racking up legal bills at a rate of about $100,000 a month. The attorney fees have been a contentious point almost since the state seized control of the trust in 2005.

A motion filed last month by the Utah attorney general's office critiqued and criticized the fees and asked a judge to reduce the attorney fees billed for the first nine months of 2014 — to $833,074 from $925,638.

Third District Judge Denise Lindberg, who has oversight of the UEP, has yet to rule on the issue. The attorney general's filing says UEP attorneys have billed for $8 million since the state seized the trust.

In Hildale and Colorado City, the attorneys fees have been cited as one reason residents there have refused to pay a $100-a-month occupancy fee required to live in a UEP home. A St. George judge last week approved seven evictions against families who refused to pay the fee. Paperwork has been filed by UEP attorneys to evict people from dozens more homes, and from a handful of businesses in Hildale and Colorado City.

Hildale and Colorado City are home to the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Jerold Williams, who used to be a FLDS bishop in Pringle, S.D., and has since been booted from the group, said on Friday that he has been told his home in Colorado City has been served an eviction notice.

Members of his family continue to live there, though they refuse to have contact with him since he was booted from the FLDS by its president, Warren Jeffs. FLDS members who follow Jeffs also are forbidden by him from paying the occupancy fees.

An eviction notice "puts people who are still trying to be in the church into an awkward position," Williams said.

"No one has any trust in what [Bruce] Wisan is doing," Williams added.

Wisan and the attorneys he has employed have long said the lawyers are necessary for all the litigation involving the trust. Since the state took over in 2005 and Lindberg appointed Wisan as fiduciary, the UEP has been sued in both states and in federal court over civil rights claims and property disputes that Wisan has said threatened to take assets from the trust and place beneficiaries at risk of losing their homes. At a 2011 community meeting in Colorado City, Wisan asked the audience to stop suing the trust so it wouldn't accumulate so many attorneys fees.

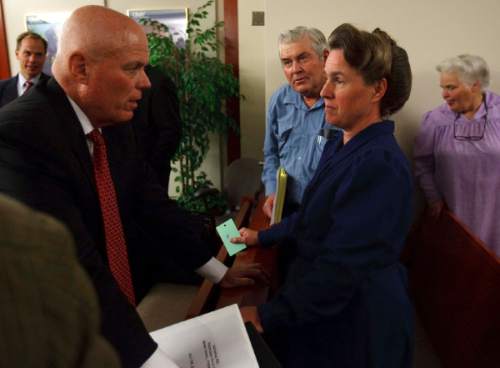

Val Oveson, the former Utah lieutenant governor who has been assisting Wisan, and has been selected by the attorneys general in Utah and Arizona to replace him, defended the legal bills again on Friday. He described managing and protecting the trust as largely a legal endeavor.

At its peak, the UEP was a party in 35 different lawsuits, Oveson said.

"If we didn't have to go through the legal hoops we've been through over the years, this would be a different story," Oveson said.

Many of those lawsuits were dismissed or settled, but a notable one remains. Elissa Wall is suing the UEP, alleging it is liable for when Jeffs forced a then-14-year-old Wall to marry her 19-year-old cousin. The parties are waiting on a ruling from the Utah Supreme Court on whether the lawsuit can proceed.

Attorneys for Wall, who originally gave her the pseudonym "MJ" when they filed the case because the allegations center on what happened when she was a juvenile, have suggested they could seek up to $30 million from the UEP.

How the UEP is defending the Wall lawsuit was singled out for criticism in the motion by the attorney general's office. It noted the UEP has three law firms representing it in the lawsuit. Seven UEP attorneys worked on one filing.

Oveson said the money being sought by Wall makes the lawsuit critical.

"That, to me, is not a good case to be criticizing attorneys fees on," Oveson said.

The UEP has filed its own lawsuits, too. Those lawsuits have been to claim property and water rights UEP attorneys say belong to the trust and to serve evictions.

The UEP also filed a lawsuit against Hildale to gain approval for a plan to subdivide parcels in the town. The UEP prevailed at the Utah Supreme Court and this year was able to give away 24 homes to people with legitimate claims to them.

Assistant Utah Attorney General David Wolf said one reason for the amount of fees appears to be the way the UEP is managed by the court. Wolf said Wisan has been letting Lindberg decide whether the fees are appropriate rather than doing what most private clients would do, which is scrutinize and contest any excessive fees.

"In this circumstance, you don't really have a client," Wolf said. "You have a court supervised trust."

Oveson disagreed with that description of the relationships between the fiduciary, the attorneys and the judge. Oveson said Wisan had been reviewing the billings before they are filed with Lindberg and occasionally asked for a fee reduction.

The Utah attorney general's office, according to court filings, spotted duplicate billings in the invoices for the first nine months of 2014. UEP attorneys said it was an honest mistake — and the attorney general's office agreed — and reduced its bill to $875,638.

But the UEP attorneys billed for the time they spent finding the errors, according to the court filings.

The attorney general's office, in the filing it sent Lindberg, says the fees are still excessive. It wants them reduced to $833,074.

Wolf acknowledges the UEP has been a party to much litigation, and Wolf complimented the way attorneys have defended the trust.

"I would just like to see some kind of control" on the fees, Wolf said.

While Lindberg could dispute or simply refuse to approve all or some of the fees, she has generally shown a deference to the UEP attorneys, especially if no other party files a motion opposing the fees.

In 2011, Lindberg ordered the state of Utah to pay the UEP to cover legal and management fees. The Utah Legislature in 2013 loaned the UEP $5.69 million. The UEP later repaid $4 million. The remainder was forgiven.

The $4 million and nearly all the other fees paid by the trust have come from sales of UEP property. The trust is said to currently have about $110 million in assets, but getting the liquidity to pay lawyers and other professionals has been slow. Oveson said some attorneys have been reluctant to work for the UEP because they weren't getting paid.

At the end of 2013, UEP accounting said it was owed $3.3 million in occupancy fees. Oveson said the Hildale and Colorado City residents who are refusing to pay their $100 a month in protest of the attorneys are increasing those legal bills.

Concerned the trust did not have a reliable stream of income, Lindberg in July approved the plan to begin serving eviction notices on people who weren't paying their occupancy fees. Unless residents vacate or pay when they receive the first notice, the eviction process requires the UEP to go to court.

"We certainly wish it didn't cost as much," Oveson said.

Twitter: @natecarlisle