This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In the past, University of Utah students who wanted to become dentists were working on dummy heads on sticks and in lab classes split up for space.

But no longer.

The university's School of Dentistry celebrated the opening of its new $36 million building Wednesday. The gleaming complex includes plenty of classroom and lab space and lifelike mannequins. More importantly, interim dean Glen Hanson said, it has a dental clinic.

The school will do more than teach tomorrow's dentists, he said. It also will help those in Utah who have little or no access to dental care.

Financed with a $30 million donation from the Ray and Tye Noorda family and other contributions, the complex is fully paid for, Hanson said Wednesday, which will allow the school to provide care many dentists can't.

The donation, he said, "gives you the flexibility to do what we're doing — to serve the underserved."

Thousands of Utahns can't afford to go to a dentist, and dentists can't afford to do the work for free or to take on many patients covered by Medicaid, with its low reimbursement rates, he said. Because of the financing of the building, the school will not have to manage debt.

The school still will seek foundation, federal and state funding to care for the underserved, Hanson said. He believes the school will take some of the charity load off local dentists.

"We're not here to compete with community dentists," he said. "I think we can partner with them and make sure people who need this care can get access to it."

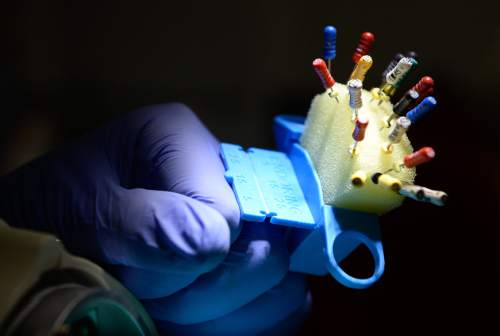

Student dentists will be able to go out into community clinics. But the building's ground floor also has a large clinic with 62 dental stations where students can work on patients, monitored by faculty dentists. The clinic includes an oral surgery suite and a suite for child patients, complete with screens, hung parallel with the ceiling, so children can watch movies as they lie in dental chairs.

Most insurance plans will be accepted, and services provided by student dentists will be half the usual price.

For two decades, Utah dental students completed their first year at the U. and then went on to study at Creighton University in Omaha to finish the remainder of their four-year programs.

U. administrators always hoped the program could become a full-fledged dental school, and the Noorda donation made that possible, Hanson said.

Ray Noorda was chief executive of Orem-based Novell Inc. and is considered the father of computer networking. He died in 2006. His wife, Tye Noorda, died last year as the Ray and Tye Noorda Oral Health Science Building was nearing completion at the U.'s Research Park.

The dental school opened in 2013, but the 43 students admitted in the first two classes had to share classroom and lab space with medical, nursing and pharmacy students before moving into the new building in January.

The plan is to expand to 40 students in each class — a total of 160 for the four-year dental school.

Half the students in each class will be from Utah, and half from other states, with priority given to those from Western states that do not have dental schools, including Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and New Mexico.

The school boasts that its cost — roughly $35,000 per year for in-state students — is about half or even a third as pricey as private dental schools in the country.

While Utah is one of the more competitive markets for dentists, resulting in lower pay than elsewhere in the country, a new U.S. Department of Health and Human Services study found the state actually has a shortage of 68 dentists when the underserved in low-income and rural areas are factored in.

The state had 2,070 dentists in 2012. By 2025, Utah will have 2,324 dentists, but a shortage of 129 dentists, the study said.

Second-year dental student Kathryn Cameron of Holladay said the new space and equipment make learning much easier. For instance, the dummy heads the students learned on last year were essentially mounted on sticks. In the new lab, they have hydraulic-operated mannequins, which can be positioned as a human patient would be.

"It's much more realistic," Cameron said.

Last year, she had a lab where half the class was in one building and the other half in another. That made it hard for the professor, she said.

"It's much more efficient to have them in one place," Cameron said.

kmoulton@sltrib.com Twitter: @KristenMoulton