This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The Paiute Indians of Utah have always existed somewhere between silvery green and fiery orange, between the bright sagebrush plains and darkened conifer slopes of central Utah and the vibrant desolation of the redrock south.

With the seasons, they shifted from farmer to gatherer, from the desert to the mountains, using their flexibility to survive among far more powerful rivals on some of the country's most resource-scarce expanses.

Even now, their lands reduced to 10 parcels scattered from Santa Clara to Fillmore, the 906 members of the tribe live in some of Utah's fastest-growing communities and in some of its most remote corners. Its five bands are independent and face different challenges. Some have choice land near Cedar City and St. George; others have isolated patches of harsh terrain.

To define the Paiute is to crate up a sand dune.

The decentralized tribe found itself in an unusual identity crisis last month when outcry over its chairwoman's dealings with Washington, D.C.'s controversial football team led to her ouster, fractured relationships among tribal members and pushed them into a national debate over sports, race, exploitation and tribal pride.

Last month, the tribe held a special election and chose a new chairwoman. As the tribe heals, members are considering how they connect to their Paiute identity and what they hope for their tribe's future.

These are some of their stories.

Patrick Charles fought to restore tribe

Patrick Charles' life's work has been, at its heart, about identity.

Charles, 61, was part of the team of Paiute leaders who in 1980 successfully petitioned Congress to restore federal recognition to the tribe's five shattered bands.

"When termination came, we didn't have anything to look forward to," Charles recalls. "Nobody had jobs. A lot of families didn't stay together. We lost our language. Kids growing up had to struggle with not having a culture."

Misty Snow dreams in tribe's treasured store

At the new See'Veets Eng convenience store, a glass case holds beadwork by Paiute elders. Non-Paiute customers peer at the signs written in English and Paiute. Over a rack of donuts, a sign reads "Peuv tuh kup (Sugar Food)."

"The old ones always had a vision of something like this," clerk Misty Snow recalls. "When it was finally here, it was a big thing."

After her past struggles with alcohol, she says, her job now has put her "on the right path. It's because we fought hard for the store. I feel privileged to be hired and work here. I want to do good for my people."

Dorena Martineau keeps Paiute culture alive

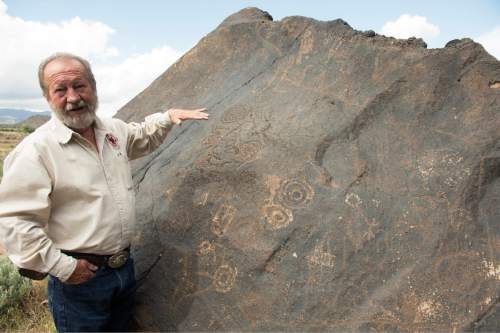

As the setting sun cuts through the perfect east-west canyon that is Parowan Gap, the warm light makes a distant memory of hail and lightning that crashed down on the Gap one night earlier, canceling a tour of the elaborate petroglyph site.

The weather wasn't bad luck, explains Dorena Martineau, the Paiute tribe's cultural resources specialist. Parowan Gap is an ancient crossroads, with markings made by multiple tribes over centuries. The desert thunderstorm may have been their reminder that some powers are higher than our own plans, Martineau says.

For Martineau, respect means listening — not just to the whispers of spirits in thunder, but to the descendants of those who created so many cultural andmarks of southwest Utah. Too often, she says, the voices of the Paiute are ignored in conversations about their own heritage.

Phil Pikyavit mourns lost language, land

Fabric lilies, daisies and sunflowers cover the burial site of Joe Levi. They're a gentle mark of ownership, left by Levi's descendants on a small cemetery that the Kanosh band no longer actually possesses.

Phil Pikyavit, a tall 74-year-old, lingers over the graves of his parents. He is one of only a few remaining Kanosh members who can speak the band's traditional Numic language.

The band got some of its land back when the Paiute tribe regained federal recognition in 1980. But the new Kanosh reservation was less than half of its old size, and it did not include the traditional burial site.

"I'd like to get that land and put it under the trust for the Kanosh Band," says Pikyavit, who is the band's chairman.

Corrina Bow hopes to help tribe heal

Through a history of enormous loss, it may be natural that the Paiute cultural traditions that have remained most complete and relevant deal with grief. Pain is faced directly, openly and as a community.

That wisdom is bedrock to Corrina Bow, the new tribal chairwoman, who was elected last month following the nationally-controversial ouster of her cousin. After a month of political conflict, unprecedented media exposure and broken relationships, Bow has a word to describe the state of her tribe: "Wounded."

"It's been really hard on everybody," Bow says. "The tribe has been through a lot of pain."

Inside

See stories of Paiute members. › A10, 11