This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Grand Canyon's sandbars are returning.

After three straight years of experimental controlled floods unleashed to push sediments down the Colorado River, the U.S. Geological Survey released a report this week declaring the seasonal gushers a success.

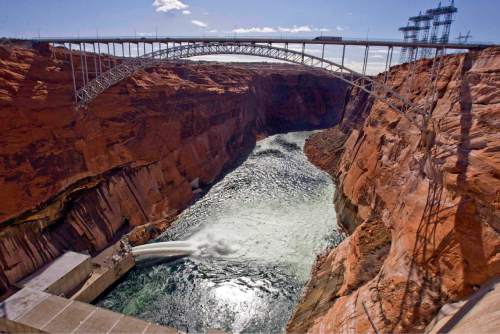

The sand deposits — ecological sanctuaries that also make great camping spots for rafting parties — disappeared after Glen Canyon Dam tamed the Colorado's floodwaters 52 years ago.

Since 1996, the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) has authorized periodic torrents — up to 45,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) — to mimic natural high-water events before the dam regulated the flow for power generation.

But under rules implemented in 2012, the high-flow events happen annually as long as conditions warrant.

"So far, so good," said Jack Schmidt, a Utah State University geologist who has led monitoring efforts in the past. "The short-term benefit in having floods in the fall appears to be good for ecosystems, and every time they build sandbars in most places in Grand Canyon."

The world's deepest canyon is hemmed by the nation's two largest reservoirs.

On the upstream side, Lake Powell is plugged by the 722-foot-high Glen Canyon Dam, which keeps both sediments and floodwaters from entering the canyon. About 95 percent of the Colorado's sediments are captured behind the dam, where they will someday fill Lake Powell and stall the towering edifice's turbines.

For now, sediments can enter the Colorado from downstream tributaries, but floods are necessary to push the silt downstream and deposit it on the river's banks.

Reclamation engineers monitor the Paria River, a Colorado tributary 15 miles below the dam, for sediment "slugs." When sediments reach a certain volume, they schedule a flood the following fall or spring.

"You don't do the high flow unless you have a big 'slug' of sediment," said Glen Knowles, Reclamation's chief of adaptive management. "It's an erosive desert stream. During the monsoon season we can get some extreme events, with 1 million metric tons in sediments."

Reclamation guidelines implemented in 2012 require high-flow events in the fall or spring if 200,000 metric tons of sand pile up at the mouth of the Paria.

Over five-day periods in each of the last three Novembers, officials opened flood gates to allow 100,000 acre feet of water to rush past Glen Ganyon's turbines in horizontal jets that could fill an Olympic-sized pool every 2.5 seconds.

"Coincidentally, nature gave us three good monsoon seasons that gave us three good Paria flood years back-to-back-to-back," said Schmidt, the former chief of USGS's Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center in Flagstaff, Ariz. "If it happens this fall, the flood will happen again in 2015."

USGS scientists have rigged remote time-lapse cameras along the canyon's 200-mile reach, training their lenses on 43 sandbar locations to document how each responds to the floods and changes over time. The data are shedding new light on how sandbars form, according to project leader Paul Grams, one of Schmidt's former students at USU.

"We are seeing floods building sandbars in different places," Grams said.

The 2012 flow hit the maximum 45,000 cfs, but the next two were less intense — about 36,000 cfs — because of a multi-year turbine-replacement program at the dam.

The smaller floods still created sandbars, but in places where the higher floods didn't.

"You can't build a sandbar as high, but a potential benefit is you build a sandbar in different places because of different hydrologic conditions," Grams said. The floods are designed to balance the amount of sediment they push down the river against those it carries out.

Grams and Schmidt are the lead authors on the study published Wednesday in EoS, the science news website for the American Geophysical Union.

Schmidt noted that the floods rapidly built up sandbars, which then eroded over the next 6 to 12 months.

"There is inevitable erosion that occurs," Schmidt said. "It's more of a sawtooth. You get benefits. They erode. You build them back up. They erode. We have learned not every site is built up by a flood.

"We have generally positive benefits, and we have more benefits when we have more sediment coming in from the Paria."

The controlled floods also appear to be flushing invasive New Zealand mudsnails downriver, according to Knowles.

"They are a trophic dead end. They are not food for anything and take up habitat used by native invertebrates," Knowles said. "[Pushing them out] improves the food base for the trout below the dam."

Researchers also have learned that sandbar formation is not making much difference for the imperiled humpback chub, which once thrived in the Colorado's warm turbid waters that now emerge from the dam clear and cold. Biologists are concerned about improving conditions downstream for non-native rainbow trout, a favored sport fish that competes with native chub and suckers.

Accordingly, the protocols have barred spring floods since they could drive rainbows deeper into chub territory by the Little Colorado.

Spring floods are allowed through 2020, but over-winter sediment buildup at the Paria was not sufficient to warrant a spring flood this year.

The floods lower the level of Lake Powell by 2.5 feet, but that water is captured downstream at Lake Mead. The balance of water between the Colorado River's upper and lower basin states is not affected, Reclamation managers say.

And the experiment does cut slightly into the electricity the dam generates.

The agency expects to release 9 million acre feet from Glen Canyon this year. Managers say the experimental floods simply speed up the schedule of releases that would happen anyway.