This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Sean Kendall, whose dog, Geist, was shot dead by a Salt Lake City police officer a year ago, wants his day in court. But a Utah law is making that difficult.

Kendall has filed a notice of claim outlining his intent to sue Salt Lake City. He also seeks to file a civil claim against Officer Brett Olsen, who shot Geist.

But a Utah law passed in 2008 poses a significant obstacle for the dog owner to sue the officer, according to Kendall's attorney, former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson.

The law, 78B-3-104, requires Kendall to post a bond to cover attorney fees and court costs for the officer. And it dictates the court award the fees and costs to the prevailing party.

"It severely undermines the rule of law," Anderson said, "while letting abusive law-enforcement officers off the hook for their violations of the state constitution and other state legal protections."

Anderson noted that Kendall does not have the money required for a bond in the case, which could drag on for months and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

During a search for a missing 3-year-old boy on June 18, 2014, Olsen entered Kendall's fenced backyard in Sugar House. When Geist, who weighed about 100 pounds, reacted to the intruder, Olsen shot him.

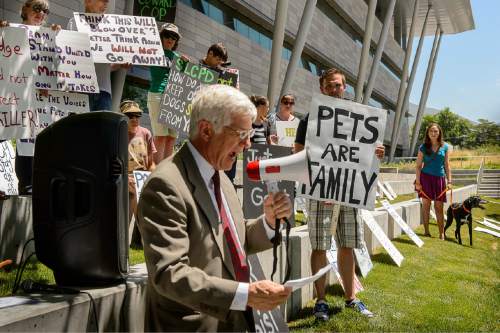

The killing of the 2-year-old Weimaraner sparked a public outcry with demonstrations and troubled residents complaining at City Council meetings.

Kendall turned down a $10,000 settlement offer from Salt Lake City, saying he wanted justice.

"It would be like, 'For $10,000 you can break into my backyard and kill my dog,' " Kendall said in a previous interview. "That's not right."

The law that is aimed at protecting police officers from frivolous lawsuits was passed in 1953 and revised in 2008 in a bill sponsored by former state legislator Jackie Biskupski, who now is a candidate for mayor.

Anderson holds her responsible for the law. But Biskupski, who sponsored HB78 that became law, said the legislation is a technical revision and cleanup bill but does not change the substance of any previous law, including the one cited by Anderson.

The section that refers to plaintiffs posting bonds when suing law-enforcement officers is on page 895 of the 1,414-page bill. Biskupski, who was a member of the House Judiciary Committee, said the law was updated over a three-year period in open committee meetings. It was approved in unanimous votes of the House and Senate as a "housekeeping" measure — one that contains no substantive changes.

John Fellows, the legislative general counsel, agreed with Biskupski's appraisal. "As I read the two sections against each other, I don't see a substantive change," he said referring to the 2008 law and the 1953 one it replaced.

Anderson disagrees, arguing the old law allowed the court discretion setting the bond, depending on a plaintiff's financial situation. Under the new law, Anderson said, the court must estimate costs and fees and set the bond accordingly, no matter what.

The newer law "exacerbates what was already a very unjust, discriminatory situation," Anderson said, "and creates enormous obstacles for people to obtain access to the courts to achieve justice."

Further, he noted the law protects only one class — law-enforcement officers. Anderson rejected the notion the law protects police from frivolous lawsuits, pointing to another Utah law that awards attorney fees and court costs in any case that is deemed frivolous.

For her part, Biskupski suggested that Anderson consider an alternative remedy: changing the law on Capitol Hill.

"I would pursue a legislative change," she said. "If his concern is about the impediments of the bond being too expensive, we need a legislative change to curb the costs of the bond."

Anderson and Kendall are waiting for a ruling on whether the law is constitutional before filing the civil complaint against Olsen and Salt Lake City in state court.

Comparing statutes

The old statute, 78-11-10:

• Before any action may be filed against any sheriff, constable, peace officer, state road officer, or any other person charged with the duty of enforcement of the criminal laws of this state, or service of civil process, when such action arises out of, or in the course of the performance of his duty, or in any action upon the bond of any such officer, the proposed plaintiff, as a condition precedent thereto, shall prepare and file with, and at the time of filing the complaint in any such action, a written undertaking with at least two sufficient sureties in an amount to be fixed by the court, conditioned upon the diligent prosecution of such action, and, in the event judgment in the said cause shall be against the plaintiff, for the payment to the defendant of all costs and expenses that may be awarded against such plaintiff, including a reasonable attorney's fee to be fixed by the court. In any such action, the prevailing party therein shall, in addition to an award of costs as otherwise provided, recover from the losing party therein such sum as counsel fees as shall be allowed by the court. The official bond of any such officer shall be liable for any such costs and attorney fees.

The new statute, 78B-3-104:

• (1) A person may not file an action against a law enforcement officer acting within the scope of the officer's official duties unless the person has posted a bond in an amount determined by the court.

(2) The bond shall cover all estimated costs and attorney fees the officer may be expected to incur in defending the action, in the event the officer prevails.

(3) The prevailing party shall recover from the losing party all costs and attorney fees allowed by the court.

(4) In the event the plaintiff prevails, the official bond of the officer shall be liable for the plaintiff's costs and attorney fees.