This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Saratoga Springs • Shooting cans of paint is never a good idea.

But at Utah's Lake Mountains, target shooters have taken the practice to a new level by placing cans on rocks marked by ancient petroglyphs.

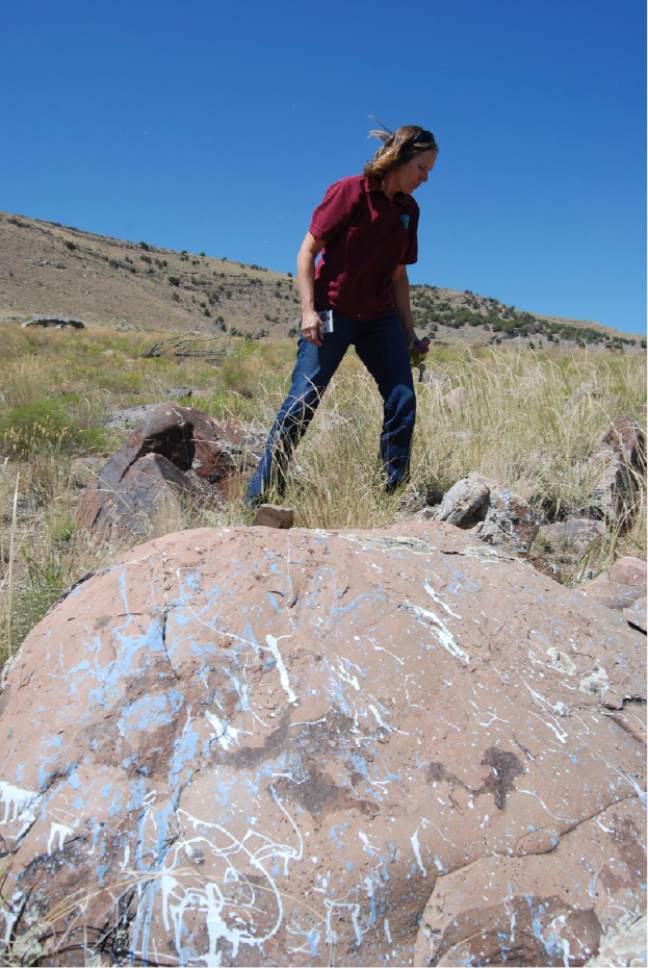

Spattered paint and bullet holes are erasing an archaeological record dating back thousands of years on public lands south of this growing enclave of subdivisions in Utah County.

"If you take paint off, the patina comes off and the rock art is gone. It's pretty irritating," Mike Sheehan, an archaeologist with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), said while inspecting petroglyph-covered rocks that now look more like a Jackson Pollock canvas than a piece of nature.

But this is not art. Gun detritus of all kinds is commonplace on the western shore of Utah Lake, where up to 50,000 people come to hone their shooting skills each year. Illegal dumps; strafed appliances, trees and rocks; and stray bullets dot this area along State Route 68, where a patchwork of state trust, federal and private lands rises above the lake.

After years of damage and conflicts with nearby property owners, the BLM has started crafting a plan to manage target shooting on 9,000 acres of federal land on the eastern slope of the Lake Mountains. In a related move, the agency proposes giving 160 acres to Utah County to operate a public shooting range.

"We are not trying to exclude a user group. We are trying to enhance the multiple uses on the land," said Bekee Hotze, the BLM's Salt Lake field office manager. "But it can't be every use everywhere.

"We are looking for voluntary compliance to protect resources. It's not working," Hotze added. "We tried to educate the public with signs, but the signs are shot up."

Land managers are gathering public comment through Aug. 30 on various alternatives, which include closing some areas to target shooting. A final decision is not expected until the end of next year.

Even gun enthusiasts acknowledge the free-for-all is hard to handle.

"I would like the closures to go away," said Scott Henry, a recreational shooter who lives in Alpine. "What they need to control is the people breaking the law."

A regional problem

Across the West, there is growing conflict between target shooters and other recreational users, particularly on lands managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Last month, a stray bullet took the life of a camper while he was roasting marshmallows with his family in Colorado's Pike National Forest.

Shooting, of course, is legal on most public land the BLM administers.

Hotze's office oversees 3.2 million acres in Salt Lake, Tooele and Utah counties, where less than 90,000 acres — about 3 percent — are off-limits to target shooting. Most of the closed areas are near campgrounds and in a nature preserve in the northern Oquirrh Mountains outside Tooele.

Still, there are numerous regulations where shooting is allowed. Fire is not to be directed at natural features or across roads, according to Utah County rules. Shooting at night is forbidden. And, land managers say, it would be nice if shooters picked up after themselves and did not use targets that break apart — bottles, toilets, TVs.

The rules are routinely ignored at the Lake Mountains.

Problems are hardly limited to litter, wildfires and shot-up rocks. Lisa Lowery fears for her family's safety and is desperate for a solution.

She has counted nine bullet holes in her home, including one in a bed. Until a few years ago, when the BLM temporarily shut off shooters' access to nearby lands, bullets came over a rise toward her property on the west shore of Utah Lake.

On Memorial Day 2012, she and her husband were working on the south side of the home when a round passed between them and struck a window. The slug lodged between the two panes of glass, a testament to how dangerous the situation had become.

"This is not a gun-rights issue. It's a personal-responsibility issue and common- sense issue," Lowery said. "If two bullets are hitting the small profile of the house each year, how many are crossing the highway and reaching the lake?"

In one 2012 incident, some school kids visiting the Knolls, near the Lowery home, had to crawl back to their bus after bullets came whistling overhead. The shots came from public land to the south, their trajectory paralleling the highway. The culprit was never identified, according to retired BLM law enforcement officer Randy Griffin.

Lowery believes only permanent closures and a dedicated shooting range will adequately protect public safely.

"It's poor choices. Our shooting community is better than that," Lowery said. "We refuse to give up our right to health, happiness and the use of our property so people can shoot on public land and have a good time."

For years, sheriff's deputies have fielded other complaints from the area's two largest property owners, rancher Blake Smith and Dean Mitchell, who hopes to develop mining claims on his property. Both declined to be interviewed.

Utah County Undersheriff Mike Forshee agrees broad closures are needed. People will still be able to hunt, he notes. Some sections of public land will just be closed to haphazard target practice.

"We can't enforce without definable boundaries," Forshee said. "If you say, 'You can't shoot here, but if you go 30 feet over there you can,' that's not right.

"You should be able to shoot," he added, "but we should able to protect it."

Fire starters

It wasn't property owners' complaints, or even Lowery's near-hit in 2012, that motivated authorities to close down nearby areas to target shooting later that year.

Rather, a rash of wildfires that summer, including one that threatened Saratoga Springs, finally forced authorities to act.

Gunfire triggered 12 of the 14 fires that summer. In response, the BLM temporarily closed 900 acres. With the help of the county and private landowners, officials later put up fences and jersey barriers along the highway to keep shooters out of closed areas.

Even so, trouble has persisted and, in some cases, intensified — particularly in connection with cultural resources.

There are some 300 rock art sites strung along 2 miles of outcroppings that contour the Lake Mountains' east slope. The temporary closures put more shooting pressure on the archaeological sites and damage to rock art has accelerated, according to Griffin.

Much of the damage is not deliberate, just incidental to undisciplined shooting.

The fire-induced closures also pushed shooters onto land managed by the Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA), where litter soon piled up. In response, SITLA shut down some of its holdings to all public access, which in turn concentrated use in other areas.

"We aren't opponents of shooting on trust lands. Bad actors are potentially ruining it for others," said Kim Christy, SITLA's deputy director. "It was a pathetic wreck out there. We have a stewardship responsibility. We can't tolerate these abuses."

According to Lowery, the "bad actors" are hardly confined to reckless young men, but include otherwise responsible adults with children in tow. She has confronted numerous shooters ignoring BLM signs indicating where not to direct fire.

The 'right' kind of target

There's no missing the impacts left by shooters and their vehicles.

Juniper trees are shot to pieces and a spiderweb of ad hoc "roads" cover the ground. "Trigger trash" includes old appliances, automobiles and bed springs that are peppered with gunfire and left for someone else to haul out.

Utah County ordinances, passed in response to the problems, restrict targets to paper, cardboard and ceramics — the kind of materials you can take home.

But, at the Lake Mountains, all sorts of questionable things are shot, including aerosol cans, fire extinguishers, signs, even bathroom commodes.

"It makes a puff and it's exciting," Hotze said. "The glass becomes a hazard. Imagine what it can to do to animals' feet.

"Is this really a family- friendly site after this happens? You have to make sure kids don't get into the paint cans and step on the broken glass."

The worst debris comes from cathode-ray tube (CRT) televisions and computer monitors, which became favored targets after the rise of flat screens made them obsolete a few years ago.

Shards of leaded CRT glass coat the ground like mosaic tiles. They are considered hazardous waste, so the TV remnants can't be removed with the rest of the trash. Instead, high-priced contractors need to be used, Griffin said.

Volunteer parties spend hours hauling out tons of trash every year.

"It can be cleaned up to a point, but when it becomes microtrash, when it has set out there for some time and been shot up repeatedly, that stuff can never be cleaned up," Griffin said. "That's not something taught in a firearms class — what you are using as a target. When you shoot something that someone else leaves out on public land, all you are doing is contributing to the problem. How are you going to clean up bottles you shot with a high-powered rifle and scattered over a large area?"

He said BLM officers issued 33 citations in 2011 to shooters, mostly for creating a nuisance — a catchall violation that applies to all sorts of misconduct that results in resource damage.

"It didn't matter how many tickets we wrote," Griffin said, "we couldn't get a handle on the problem."

'Responsible, law-abiding citizens'

A man out shooting paper targets this months expressed dismay with his fellow shooters' lack of etiquette.

"I feel disgusted with what I consider my community," said the Sandy man, who would identify himself only as Tony, while taking a break from shooting at paper targets with a 9mm Smith & Wesson. "I know there are super-responsible shooters that it also sickens.

"We want to come out and do this for recreation. We are safety-first. We are environment-first," he said. "But there are those who are not, and that sucks."

Still, Tony worried the planning process would lead to ever more restrictions and closures, requiring him to travel even farther distances to practice.

"It's just fun," he said. "As responsible, law-abiding citizens, I feel it is something people should be able to do — as long as they do it properly."