This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

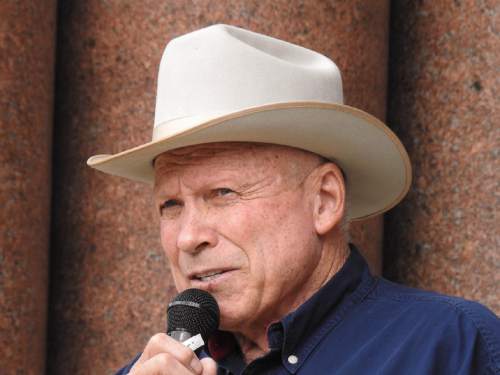

William "Dub" Lawrence is a man obsessed with truth.

When his son-in-law was killed in a SWAT standoff in Farmington, Lawrence — a former police officer and Davis County sheriff — gathered every possible document, photo and video clip that could explain what happened during the 12-hour encounter Sept. 22, 2008.

The same SWAT team Lawrence created in 1975 shot Brian Wood with a stun gun while he was barricaded in his truck, then hit him with pepper balls before a sniper ultimately shot him in the face.

Police say they reacted to Wood, a 37-year-old part-time firefighter, firing a gun at them.

But Lawrence believed there was more to the confrontation. For years, he bottled up anger, resentment and bitterness as he obsessively collected information to see if he had been lied to by his former police force.

It was this passion and fixation that, in 2012, would connect Lawrence with two Utah filmmakers — and eventually lead him to being the subject of the new documentary "Peace Officer," which is scheduled to be released nationwide this week.

"I started the SWAT team in 1975," Lawrence said in the film. "The intent was noble. The intent was to have the capability, the weaponry, the training, the ability to neutralize or defuse violent situations. As I stood there and watched and witnessed what went down on the 22nd of September, I knew how they should be conducting their operation. I knew the procedure, the protocol, the tactical operations that would be effective. I was disappointed."

'Trying to learn the truth' • As Wood's father and wife fought a wrongful-death court case for four years, Lawrence told The Salt Lake Tribune recently that he focused on finding all of the information he could about the fatal shooting. He filed public records requests and obtained video footage. He bought a computer and was working to edit the footage but acknowledges he was in over his head when it came to using the software.

That's when he had a chance meeting in 2012 with Texas-based film professor Scott Christopherson, who was friends with Lawrence's son.

Christopherson said he agreed to help with the editing, and as Lawrence showed him the analysis he had done of Wood's shooting, he realized this "compelling, charismatic and kind of obsessive" person would be a great subject for a film.

That's when Brigham Young University film professor Brad Barber got involved. The two directors began their first shoot inside Lawrence's airplane hangar in North Salt Lake — where Lawrence has lined the walls with photos from Wood's shooting, as well as two other Utah police shootings that he independently investigated for the families of Matthew David Stewart and Danielle Willard.

Barber said it was Lawrence's personal story that made him a powerful character who anchored the film, which focuses on the increased militarization of police in the United States.

"He comes from a long line of law enforcement," Barber said. "He's very dedicated to justice. However, he's also a victim. He has this incredibly unique perspective that is extremely rare and extremely valuable."

But the documentary — which will first screen in Utah on Sept. 25 at the Tower Theater — doesn't focus on Lawrence's story alone. It also documents Lawrence's investigations into the 2012 shootout at Stewart's Ogden home, which left one officer dead and five others wounded, and the police shooting of 21-year-old Willard in West Valley City later that year.

The film follows Lawrence as he finds new evidence left behind by police, uses lasers and string to reconstruct bullet trajectories and analyzes glass patterns and other evidence as he attempts to uncover what happened during those deadly police encounters.

Lawrence said he took an interest in Willard's and Stewart's cases as he was investigating his own son-in-law's death, and he quietly began gathering photos pertaining to the two cases and hanging them on his walls.

It wasn't until a candlelight vigil held after Stewart committed suicide in jail in May 2013 that he met with Stewart's father and began going to the Jackson Avenue home to collect evidence where the gunbattle occurred. He later helped Willard's mother, Melissa Kennedy, reconstruct the scene where West Valley City Detective Shaun Cowley shot and killed Willard as she backed out of a parking spot.

"It's a work of love and devotion," Lawrence said of investigating the other cases. "And trying to learn the truth."

Lawrence came to several controversial conclusions about the various shootings, including that his son-in-law was incapacitated and could not have fired at officers when he was shot by the sniper, that Cowley was not in the path of Willard's vehicle when he shot her and that Stewart did not fire first at officers — as prosecutors have claimed. He also introduces the possibility that one of the officers may have been hit by friendly fire in Stewart's home.

Lawrence, who now works in water- and sewage-pump repair, said he didn't seek to be provocative as he looked into the cases.

"I don't want to offend people," he said. "I want some good to come from the losses that we have all experienced."

The film • Barber and Christopherson use Lawrence's story and the other Utah cases to illustrate the growing national trend toward more heavily armed and militarized police forces, and the use of SWAT and strike-force teams to investigate drug crimes.

The directors said they chose to feature Utah cases almost exclusively because they wanted to remain focused on Lawrence and his experiences.

"We had access to Dub and what he had access to," Christopherson said. "... We really focused on Dub and Utah because we had intimate access to all of these cases."

But the two said they wanted to ensure the film did not just represent the views of those whose loved ones were killed in police shootings — they sought to give a voice to police officers as well.

In the film, two members of the Weber-Morgan Narcotics Strike Force team who were involved in the shooting in Stewart's home spoke about their perspectives that night, and two Utah sheriffs lend their voices to speak out against the idea that police are becoming more militarized.

Barber said they filmed the project over two years and that other national events — such as the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. — happened just as their filming wrapped. He noted it "was tempting for a little bit" to expand their film outside of Utah, but said they ultimately kept their focus here.

"I feel like the most authentic way to understand a complex [topic] is sometimes through a personal story," Barber said. "We've always been most interested in telling Dub's story, and that involved other people he was trying to serve."

The documentary was first screened at the South by Southwest film festival in Texas in March, where it was awarded both the Grand Jury and Audience Award in the documentary category. It has been screened several times since and is set to be released in Los Angeles and New York City this week. Along with a weeklong run at the Tower Theater beginning Sept. 25, the film will be at Salt Lake City's Gateway Megaplex Theatres for a week, beginning Oct. 2.

Christopherson and Barber said they hope their film will not be divisive, but that it will start constructive discussions about policing in America.

Lawrence said he wants the documentary to not only start a dialogue about police shootings, but also spark conversations about laws and policies that can lead to dangerous encounters. He said he hopes lawmakers will reconsider government immunity given to police officers, stressing the need for more transparency, accountability and equality.

"We can't bring Brian back," he said. "We can't bring Danielle ... or any of these kids back. They're gone. We have to move on with life and make things better and learn from our mistakes, with all sides willing to come to the table and improve."

Twitter: @jm_miller