This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Today, Mormon forger and murderer Mark Hofmann likely would have a tougher time selling his fake documents — and his seriously skewed view of the origins of the LDS Church — than he did 30 years ago.

Hofmann preyed on the urge to hide unwelcome information so he could pass off counterfeits as real. Mormon officials, among others, fell right into his trap.

Back in October 1985, when Hofmann killed two people with homemade pipe bombs in an attempt to divert attention from his double-dealing and dishonesty, the Utah-based church restricted access to its historic archives and promoted only a canonized — some would say narrow — view of the faith's founding.

No more.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has opened its archives, posted thousands of documents online, produced groundbreaking research on its past and published a dozen recent essays on controversial historical developments.

"It's been a revolution," says Ronald W. Walker, a retired Brigham Young University professor of history who has been involved in telling the Mormon story for more than four decades. "We now understand we can approach difficult questions and do it successfully."

Exposing the forgeries was the beginning of a new era, says Jan Shipps, a prominent historian and author of "Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition."

Would Hofmann have been able to market fake documents, she wonders, "if we had had the Internet at that time?"

But vulnerabilities still lurk — or lurk again — in the little-known field of document collectors.

—

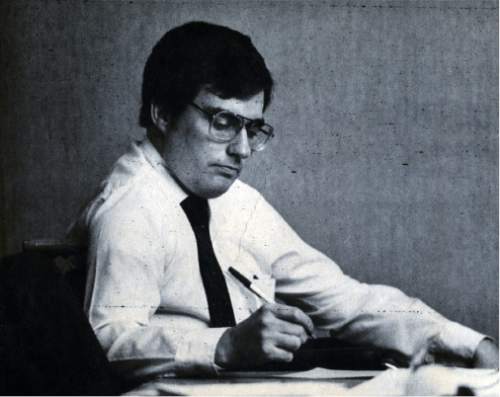

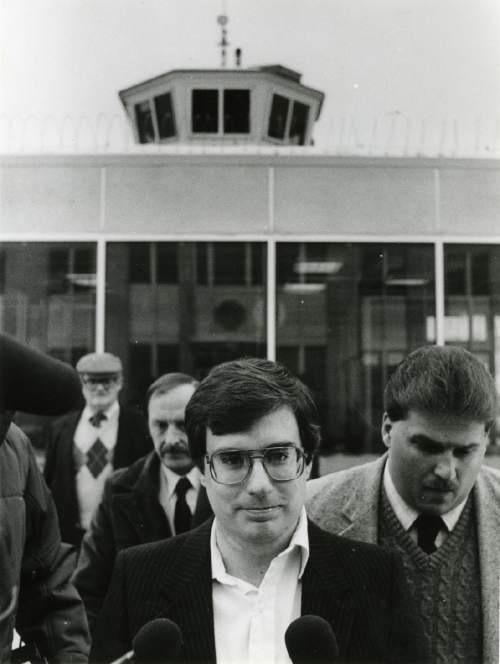

A star was falling • Hofmann, a returned Mormon missionary, Utah State University pre-med student and clean-cut, bespectacled husband, stepped into the spotlight in 1980, when he claimed to have found a piece of parchment stuck between the pages of a 17th-century Bible.

On one side of the page were hieroglyphic markings similar to the ones LDS Church founder Joseph Smith said he copied from gold plates in the 1820s. Smith had given a page with such markings to an early Mormon convert, Martin Harris, to show to Charles Anthon, a scholar of ancient languages.

After widespread publicity, Hofmann donated the document, known as the "Anthon transcript," to the church for $20,000 in trade.

Thus began the forger's lively business in bogus Mormon and other documents — including letters purportedly written by Abraham Lincoln, Daniel Boone and Betsy Ross, and a piece of doggerel that fooled Emily Dickinson scholars for years. They commanded increasingly large sums.

In 1984, he claimed to find the so-called "Salamander letter," a Harris letter that described Smith's experience of finding the gold plates upon which the Book of Mormon was written. In the official version, Smith got the plates from an angel. In this letter, "the spirit transfigured himself into a white salamander in the bottom of the hole."

LDS Church leaders declined to buy it, so businessman Steve Christensen purchased it for $40,000 and donated it to the church.

But then the forger got ambitious — even greedy – offering whole collections of papers, including lengthy journals and letters from an early Mormon apostate, William McLellin.

After Hofmann sold the same collection to several buyers and collected a huge sum of money for materials he couldn't produce, he plotted a murderous diversion to buy himself time.

—

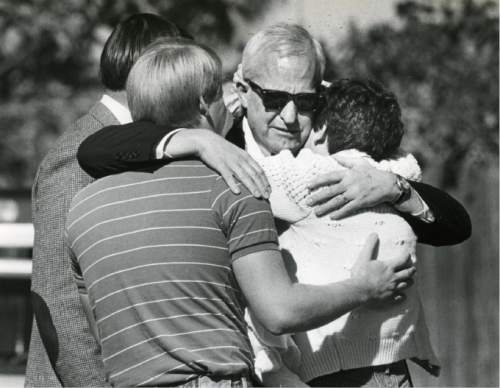

It all explodes • On the morning of Oct. 15, 1985, Hofmann placed a package wrapped in brown paper outside Christensen's office in the Judge Building in downtown Salt Lake City. When the 31-year-old businessman picked it up, it detonated, shattering the quiet of the hallway. A secretary from across the hall rushed out to Christensen, sprawled on the floor and dying.

Shortly after that, a bomb went off in a tree-lined Salt Lake City suburb. Kathleen Webb Sheets, wife, mother, grandmother, had picked up a package addressed to her husband, Gary Sheets, Christensen's former partner. She died instantly.

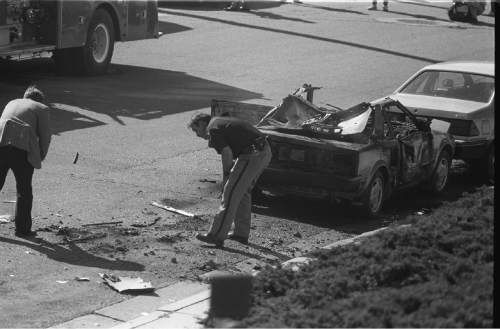

The next afternoon, a bomb went off inside Hofmann's car, wounding him and destroying all the papers in the trunk, which he claimed were the promised documents.

National attention turned to Hofmann and his dealings, but no one suspected the extent of his deceit.

Not a future LDS Church president, the late Gordon B. Hinckley, who had been instrumental in obtaining some of Hofmann's finds. Not Mormon historians like Walker, who tried to fit his documents into what was known about LDS history. Not fellow document dealers, like Curt Bench, who assumed that Hofmann himself might be in danger.

Not even his then-wife. Today, Dorie Olds maintains she had no reason to suspect that her husband had been lying to her, possibly from the first months of their marriage.

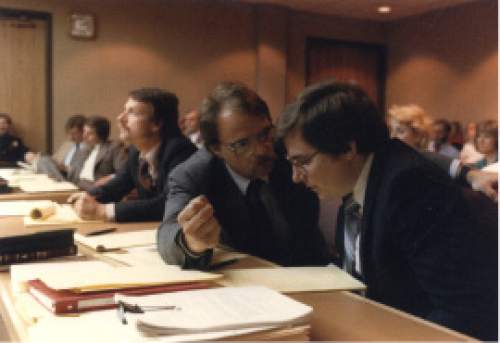

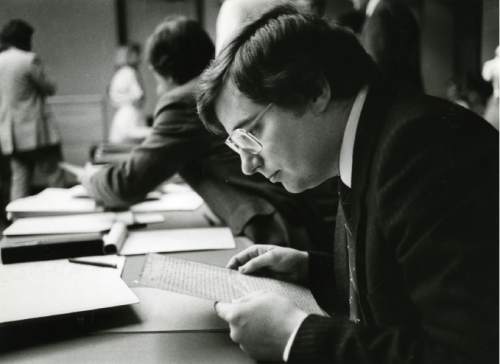

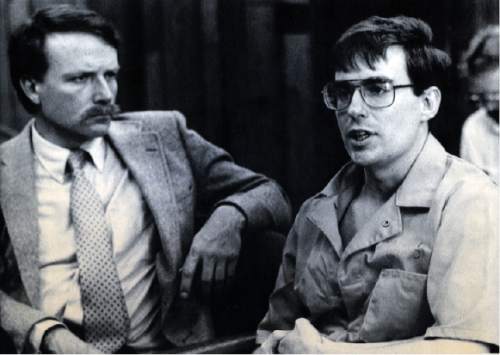

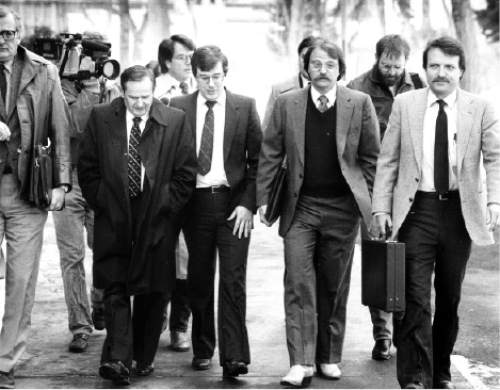

It was not until the first months of 1986, when police arrested Hofmann and laid out the evidence of murder and massive forgeries, that friends, family and the public came to know the magnitude of his deceptions.

A year later he would plead guilty and be sentenced to life in prison.

That left Mormon historians to reassemble what they knew about their past, how they had been affected by Hofmann — and how to avoid ever being duped again.

—

A new approach • Soon after the Hofmann episode, the church's historical department hired Richard E. Turley Jr., a young Mormon lawyer with a love for the faith's past.

With approval from top leaders, including future church Historian Marlin K. Jensen, Turley began helping to open the collection to outside researchers.

Turley persuaded Mormon officials to let him and Walker have access to the church's holdings on the Mountain Meadows Massacre — and to report the story of the Arkansas wagon train attacked in Utah, no matter where the documents took them.

Later, the LDS Church launched the landmark Joseph Smith Papers Project, publishing everything related to the church's founding events.

Turley, who is now assistant church historian, also implemented strict protocols for evaluating documents, including some scientific testing, but paying particular attention to an item's provenance, where it came from and who had owned it.

"We have implemented greater security measures" regarding the use of the church's own materials, he says now. "We also make greater use of digitizing so if documents are changed, we can compare them to older versions."

Mormon historians also are more comfortable with the messiness of Mormon history, Turley says. "When you look at the totality of the evidence, the essentials of the faith remain."

There's a lot more confidence in history "and in the overall documentary record — regardless of what individual pieces would show," Turley says, "than there was 30 years ago."

—

The veil of time • After Hofmann's frauds were exposed, the LDS Church simply stopped buying documents for a while, says Bench, a document and rare-book dealer who knew the forger well.

Most people presume that documents began to be tested scientifically, and some were, he says, but many of Hofmann's documents passed such tests.

"A lot of us wondered if we should have anything to do with documents anymore,' says Bench, owner of Benchmark Books, "but most discovered if you are careful and keep everything aboveboard, good can come of it."

He is, however, convinced that there are still many Hofmann fakes around that no one knows about.

Ryan Roos, a young Mormon collector who has been in the business 15 years, agrees.

When he sees a large collection and it includes Hofmann's business card, Roos says, he is suspicious. There is still a ton of money on the line — some collections can go for as much as $100,000 to $200,000 or even $1 million — so private collectors would not be eager to announce any connection to Hofmann that could render documents worthless.

A dealer's reputation is "everything," says Roos, co-owner of Provo's Writ & Vision shop. "I won't touch anything that might be a forgery and will identify these things immediately to the seller."

Provenance, he says, is the only safeguard.

And openness. "It's a new Mormon world and a refreshing world, the right world," says historian Walker. "We can honestly say truth is truth and we can confront it."

That's what history should be, he says. And also life.