This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

As children and adults alike excitedly explored the normally secret wings of the Natural History Museum of Utah on Sunday, Bill Thomas engaged them in conversation amid a stunning array of tools, charts and other objects.

As it does every year, the museum unlocked the doors this past weekend to its hidden collections — including shelves upon shelves of dinosaur bones — and the workshops where they bring microscopic and ancient scenes to life.

Thomas, who prepares such exhibits, happily conversed over the nonstop chatter of curious visitors about the trick crews use to give an outdoor scene the scent of fresh-cut grass — imbuing the museum's artificial moments with an immersive reality.

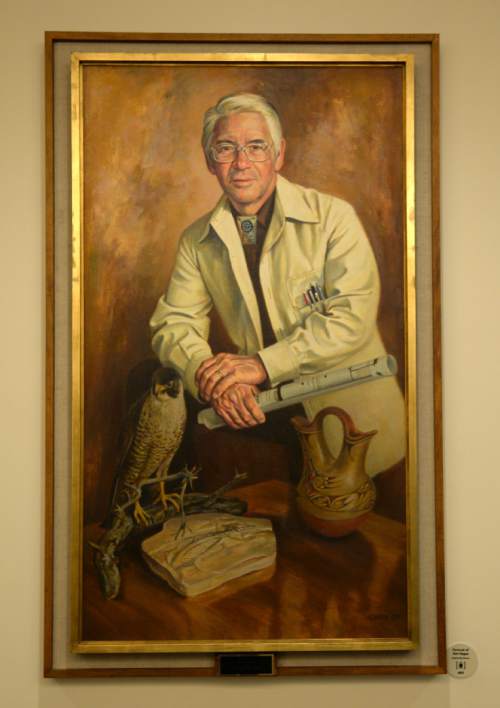

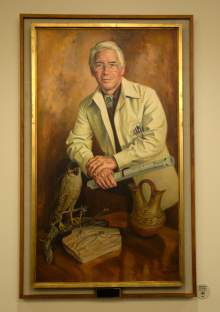

"This wing is the Don Hague Wing," Thomas said, referring to the bustling workshop around him and the collections next door. A painting of Hague, a gentleman with white hair and a lab coat, hangs in a hall just outside, greeting visitors with a quiet smile.

Hague devoted his life to the part-library, part-laboratory, part-classroom — ascending from the museum's first paid employee in the 1960s to director. From getting his hands dirty crafting prehistoric animals to securing priceless artifacts, Hague made the museum what it is.

Topping it all off, Thomas said, "he was just the nicest guy in the world."

After his health declined, Hague died Wednesday. He was 88.

"It's a huge loss," said Hague's successor, Sarah George, who brought the museum from where Hague oversaw it, on the University of Utah's Presidents Circle, to its new home near Red Butte Garden. "He truly created the museum."

As a schoolboy, Thomas — like hundreds of thousands of children — marveled at Hague's work as he walked the museum's halls at its former home. It was a magical place.

Hague had no such shrine to Earth's natural history and artifacts as a child, growing up in the Sugar House of the 1920s and '30s. Back then, the eastern Salt Lake City neighborhood abounded with streams and game, and a person could follow the railroad tracks to Parleys Canyon.

The idea of working as a curator arose during World War II when, as a U.S. Navy reservist, he was stationed in Chicago, where he discovered the Windy City's renowned museums: the Field Museum of Natural History and the Art Institute. The Museum of Science and Industry showed him the power of hands-on exhibits that would influence many of his later endeavors in Utah.

While on leave, he proposed to Lorna Dangerfield, his sweetheart since the fifth grade. She said yes, and they married two years after the war.

The newlyweds bounced around the country until they returned to Salt Lake City, where Hague found his life's calling at the Utah Museum of Natural History. Its founder, archaeologist Jesse Jennings, hired Hague in the 1960s as a curator — and the museum's first paid employee — at a time when cultural and natural objects were flowing into the U.

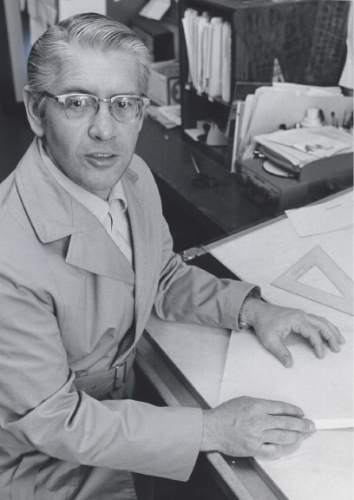

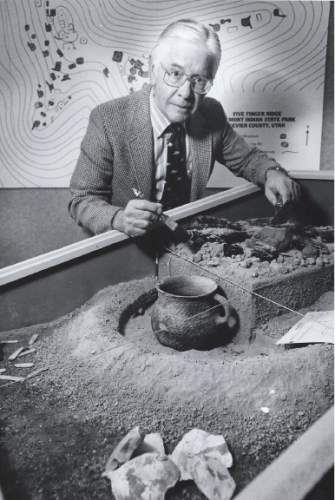

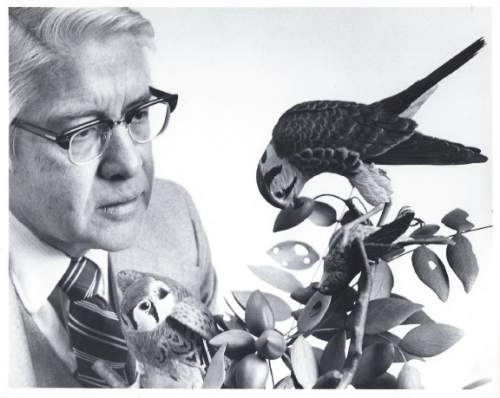

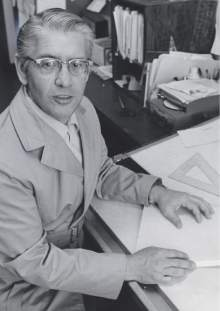

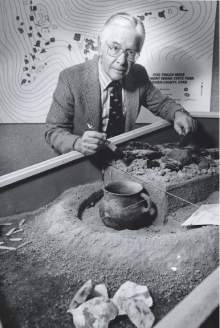

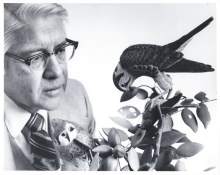

As a zoologist and artist, Hague planned, designed, researched and built exhibits for the fledgling archive. He reveled in getting his hands dirty in the museum's shop. He loved applying his art skills to science — and his work was well-represented throughout the exhibits. There was the diorama of a mastodon being killed by prehistoric men. There was a sculpture of a distant ancestor to the modern horse.

In 1973, he became the director and oversaw the museum's flourishing growth.

Under his guidance, the museum acquired a number of important collections, including Anasazi artifacts collected by the U. from Glen Canyon before the damming of the Colorado River and the creation of Lake Powell. Hague's coup, though, was the acquisition of the Buranek Mineral Collection, valued at $1 million.

While tens of thousands of children walk its halls every year, the museum began making an even bigger imprint with its lecture series. Hague believed that the U. was a place for active debate and expression. As he put it in 1992, the museum "has a responsibility to take a stand on issues we feel strongly about."

Hague left behind a museum much bigger than the one he led. He had hired 45 employees personally. The museum's budget mushroomed from about $15,000 to nearly $1 million. And it became an institution that serves indispensable roles to Utah.

What began as an addition to the school, and a showcase for Utah's natural wonders, evolved into a state agency charged with collecting and protecting the state's archaeological and paleontological treasures. The Legislature also mandates that the museum foster and oversee development of similar facilities throughout the state. Museums across Utah — as far south as the St. George Art Museum — benefited.

"In building his museum, he also built expectations for excellence in the museum field in Utah," said Ann Hannibal, whom Hague hired as a researcher in the museum's earlier days and now works as its associate director. He was "a very thoughtful man" with a keen understanding of the community around him, and "a true gentleman."

Through the years, Hague's directorial responsibilities pulled the artist and designer away from the workshop. In the early days, Hague spent about half his time researching and designing exhibits. By the time he retired in 1992, he was spending almost all of it devoted to administrative duties — raising money, mainly.

Thomas, surrounded by the tools of the new museum's workshop, was sure Hague "would have loved coming in here and hiding from his more official and obnoxious duties. To come down [to the workshop] and monkey around with tools is what he would like to do."

As much as he invested in the museum's original digs — a three-story neoclassical building with huge windows — Hague always hoped for a new home. In a 2011 interview, he recalled how staffers used to store the museum's objects, including human remains, in walk-in freezers.

"The condition of the collections was terrible," he said, "scattered around the campus, pots inside of pots, and bugs everywhere."

Opening in 2011, the new museum is an expansive, five-story building with soaring spaces full of dinosaurs, an archaeology pit, biology workstations, stunning dioramas and improved storage for a continuously growing collection.

"The new building exceeds my dreams manyfold. I'm really thrilled," Hague said upon its completion. "This is the realization of the ultimate in care and conservation for those collections."

Hague still dropped by the new place. He knew everyone and everyone knew him.

"The place would just light up when Don and Lorna came to say hi," Thomas said. Everyone wanted to "talk with him, because he was such an interesting fellow."

Lorna, Hague's greatest joy and love, survives him.

"Oh my gosh … talk about a love affair that went on to the very end," George said. Lorna, who has a passion for dance, is "very engaged in community dance groups," George said. "Don was so proud of that."

Hague was proud of his children and grandchildren, too. As enthusiastic as Hague was to attend museum events after he retired, George said, he declined invitations when his grandson had a football game or his granddaughter had a dance performance.

Hague taught his appreciation for the beauty of the world to his family, even with just a simple nature walk, according to his obituary.

Besides his wife, Hague is survived by his five children, 21 grandchildren and 33 great-grandchildren.

The museum plans to host a celebration of his life and contributions Friday from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. His funeral will be at 11 a.m. the next day at Larkin Sunset Gardens Mortuary, with a visitation before the service at 10 a.m.

Twitter: @MikeyPanda