This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Provo • Boy Scouts are taught to leave their campsite better than they found it.

Hired to clean up the dumpster fire that Gary Crowton left when he resigned under pressure in early December of 2004, Bronco Mendenhall did just that in his 11 seasons at BYU, winning 70 percent of his games with earnest, overachieving players who mostly stayed out of trouble, upheld the values of the school and its ownership and won the games they were supposed to win while struggling to win games in which they weren't favored.

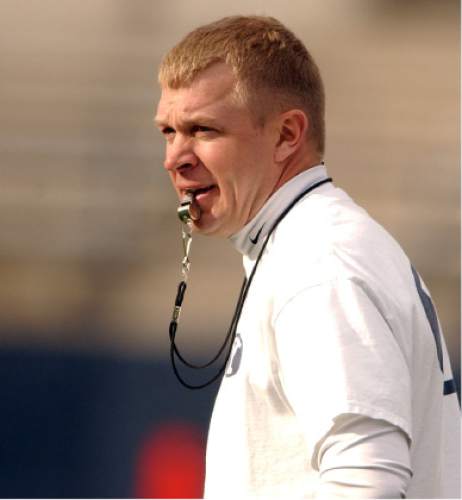

The clean-living, boyish lover of surfing, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, cutting horses and plain, old-fashioned hard work will leave that as his primary legacy — the program is in much better shape now than it was 11 years ago — and head east, way east, to attempt to resurrect another downtrodden college football program.

"Good for Bronco," said former BYU quarterback John Beck. "He leaves a legacy of bringing a program back to glory, and now he gets to take what he learned doing that at BYU and apply it at a place with not as many restrictions on recruiting and all that."

Yes, Virginia, there really is a football coach named Bronco, a Bob the Builder kind of guy, sans the cartoon figure's ever-present smile, who will bring a lunch pail to work, literally, unless that $3.25 million annual salary the Cavaliers will pay him persuades him to give up peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and canned tomato soup for takeout and an occasional lunch away from the office in Charlottesville.

Whatever one's opinion is of the job the 49-year-old Mendenhall did in Provo after taking over a program that suffered through 5-7, 4-8 and 5-6 seasons before he got the job on Dec. 13, 2004, he won't be soon forgotten.

His impact on the program, the culture of relentless hard work, commitment and dedication he established to overcome shortcomings in overall talent and speed, will be felt for years to come.

"I like to build," Mendenhall said in a tearful news conference Friday night in a lobby down the hall from his office decorated with artwork from his uniquely named three sons — Cutter, Breaker and Raeder — and a never-cluttered desk with his familiar LDS scriptures always nearby.

That's another element Mendenhall brought to the program — an emphasis on faith and aligning it with the church that owns and operates BYU — that made his bosses happy, but others not so much when it interfered with on-field results.

It had become evident the past three or four seasons that Mendenhall's building effort had hit a roadblock at BYU. His work here was finished. His program hit a plateau. It had stopped rising like it did those first six or seven years to which the always-positive Beck referred, having played for both coaches and having helped Mendenhall win his first conference championship in 2006.

BYU's well-known restrictions on recruiting, the rise of its chief recruiting rival when it left for the Pac-12 and a vastly different college football landscape that sent BYU into independence in 2011 have caught up to the Cougars. Three straight 8-5 seasons are evidence of that. This year's 9-3 run heading into the Las Vegas Bowl, which he will stick around long enough to coach the Cougars in before moving his family to the East Coast, was impressive given the fact that two of his best three players — running back Jamaal Williams and quarterback Taysom Hill — basically missed the entire season.

But with a killer schedule looming in 2016, the writing was on the wall. Mendenhall had grown increasingly frustrated with each passing year, several former players told The Salt Lake Tribune on Saturday. A good chunk of that frustration lies within the fact that BYU does not belong to a Power 5 conference, and prospects don't look promising, at least for the near future.

Beck said it was "telling" from Mendenhall's news conference Friday when he mentioned how he sits down with his wife, Holly, at the end of every season to examine his future.

The man to whom every BYU football coach will be compared to from here to eternity, LaVell Edwards, said Friday's news "came out of nowhere and totally caught everybody off-guard." The legendary coach said Mendenhall will be remembered for "doing a nice job" at BYU under increasingly difficult circumstances.

As for who he would like to see become the fourth coach at BYU since 1972, Edwards deferred.

"No way I am going to say anything about that," he said with a laugh.

Beck also declined to give a name, saying he hoped the new coach maintains the core principles — spirit, tradition and honor — that Mendenhall established.

Mendenhall's timing was good at BYU, having replaced the man who replaced the legend, and Edwards predicted similar success for him at Virginia, where departed coach Mike London went 4-8 this season.

Mendenhall leaves with a 99-42 record and a chance to get to 100 wins in the bowl game, a milestone he said Friday is important to him. His teams finished ranked in both major polls four times in 10 seasons, with a good possibility of making that five if they win the bowl game against what could be rival Utah.

But he also leaves behind a reputation of not be able to win the really big games. Fans who were not satisfied with his performance often pointed to his four-game losing streak to the Utes from 2010-13 as one of his failures.

"Towards the end of his stay, he got under-appreciated when BYU started losing games we probably should have won," said Cody Hoffman, a non-LDS recruiting gem Mendenhall discovered in rural Northern California who became the most-prolific receiver in school history. "Some BYU fans have unrealistic expectations. Look at this year, a nine-win season with a backup quarterback against that schedule? That's pretty good."

Linebacker Brandon Ogletree, who put the bite into several of Mendenhall's defenses from 2009-12, said the coach's lasting legacy at BYU will be how much he cared for his players as individuals and how hard he worked to help them succeed off the field as much as on it.

"He's a man of integrity, first and foremost," Ogletree said. "His thing was to 'embrace the grind' and he did that every day; was the first one there and the last one to leave. He would never ask us to do something he wouldn't do himself."

Ogletree said Mendenhall's detractors were the people who knew him the least and his biggest supporters were the people who knew him best, his players.

"I haven't talked to a former player yet who didn't have the utmost respect for coach Mendenhall," Ogletree said. "On the other hand, BYU fans probably didn't appreciate his depth of knowledge, his game-prep brilliance, and how much he knows about football."

Twitter: @drewjay —

BYU under Bronco

2005 • 6-6, lost to California 35-28 in Las Vegas Bowl

2006 • 11-2, won MWC championship, defeated Oregon 38-8 in Las Vegas Bowl

2007 • 11-2, won MWC championship, defeated UCLA 17-16 in Las Vegas Bowl

2008 • 10-3, lost to Arizona 31-21 in Las Vegas Bowl

2009 • 11-2, defeated Oregon State 44-20 in Las Vegas Bowl

2010 • 7-6, defeated UTEP 52-24 in New Mexico Bowl

2011 • 10-3, defeated Tulsa 24-21 in Armed Forces Bowl

2012 • 8-5, defeated San Diego State 23-6 in Poinsettia Bowl

2013 • 8-5, lost to Washington 31-16 in Fight Hunger Bowl

2014 • 8-5, lost to Memphis 55-48 (2OT) in Miami Beach Bowl

2015 • 9-3, will play in Las Vegas Bowl on Dec. 19

Total • 99-42 overall, 6-4 in bowl games