This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Even at the height of his popularity and visibility in the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. remained — at his core — a Baptist preacher.

He galvanized the faithful by drawing on biblical phrases, stories and metaphors about justice that would stir the souls of Christians everywhere, but especially those who filled the black churches Sunday after Sunday. He quoted Hebrew prophets as well as Jesus Christ and St. Paul to move the black churches to act and white Americans to understand.

"We will not be satisfied until," King told the enraptured throngs gathered on the Washington Mall for his "I Have a Dream" speech in the summer of 1963, " 'justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream ' " — an allusion to the Old Testament book of Amos.

In the final speech before his 1968 assassination, "I've Been to the Mountaintop," King compared himself to Moses leading his people out of bondage in Egypt and later conversing with deity.

God "allowed me to go up to the mountain," the activist said. "And I've looked over, and I've seen the promised land."

King's movement was, some scholars say, the last moment in U.S. history when a religious leader could speak with such moral authority to the whole nation.

As the country prepares to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day on Monday, plenty of racism persists — police brutality, mass incarceration of blacks, economic discrimination, poverty — but the people leading opposition to that racism do not necessarily come from the black churches.

Though there are theists, theologians and clergy involved in the Black Lives Matter movement, some others are younger and not religious at all.

"They are looking at how systemic racism is today," explains Janan Graham-Russell, finishing up her master's degree in religious studies at Howard University in Washington, D.C., "not through a lens of sin."

The way to battle racism has changed, too.

"It's the same devil," she says, "but in a new coat."

—

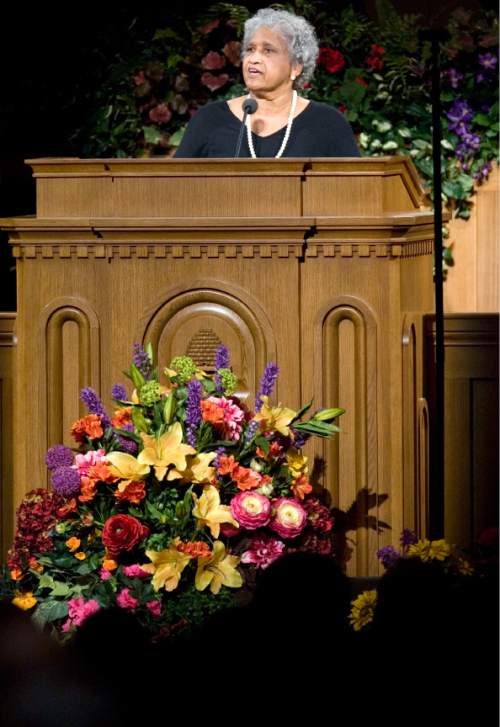

Without parallel • It is hard to compare King with anyone else, says Catherine Stokes, a black Mormon convert and retired public-health professional who now lives in Salt Lake City.

"My daddy took me as a child to hear King preach at Soldier Field [in Chicago]," Stokes recalls. Her father told her, " This man is going to make history. "

He was not flawless, but unique, she says, "prophetic, visionary, a strategic thinker, accomplished intellectually and educationally, grounded in spiritual roots."

"Martin," she says with affection, "had vision, and that leadership quality which leads people to heights they would not have attained, and sustains them in persevering."

When King was gunned down, Stokes says, "we lost leadership on all those levels."

"It's not that the black church went away," says Graham-Russell, whose emphasis is on ethics and social justice. "It's just that the church's role somewhat shifted."

Other groups such as the Black Panthers and black nationalists took the fight in different directions, she says, "and the church went back to the idea of doing charity and working in neighborhoods, but not pushing for legislative reform."

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a King disciple, and the Rev. Al Sharpton still are working to end discrimination and other racial issues, Graham-Russell says, "but their voices are not as strong."

And the goal of reaching the promised land, where people of all colors live in peace?

"We have to make it for ourselves," she says. "It is not going to be given."

Graham-Russell's own faith, Mormonism, barred black men and boys from being ordained to its all-male priesthood and black women from entering LDS temples until 1978.

Even so, says the scholar, racist views continue among some Mormons, and few leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have spoken out against them.

"The issue of social justice doesn't resonate in the LDS Church the way it does in black churches," Graham-Russell says. The Utah-based faith "still has the same system that not only created the ban, but maintained it. Racism doesn't just end when you say it does."

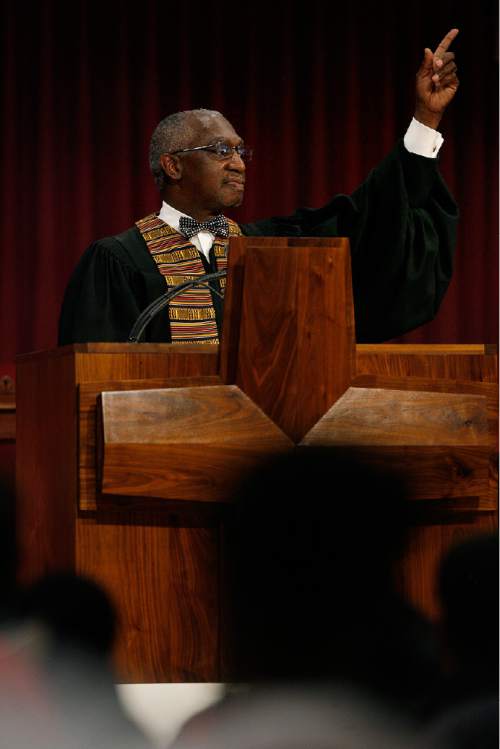

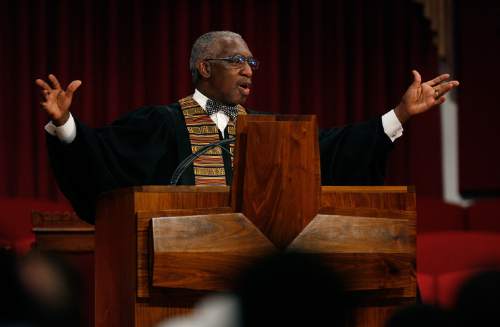

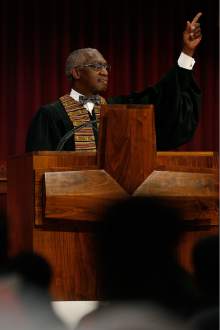

During King's day, the only organization that "we could turn to was the church," says the Rev. France Davis, longtime pastor at Calvary Baptist Church in Salt Lake City. "When he speaks of a beloved community or brotherhood or justice, he cites the prophetic voices in Scripture."

These days, Davis says, Americans have "other priorities and are not as steeped in that kind of language, especially those leading the modern movements."

Davis, who met King and marched for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., says the Black Lives Matter effort is "not rooted necessarily in biblical language and the church."

"But it's still a powerful movement," he adds, "still led by those who have a moral compass."

These youthful activists are raising awareness of "senseless police shootings in Cleveland, New York and Baltimore, to name a few," the pastor says. "We all care about educational opportunities, housing that is affordable, decent and safe. And health care for all people."

Racism in the nation and in Utah, Davis says, "is alive and well." The laws may have changed, but many attitudes and behaviors haven't.

—

Words have power • The Rev. Corey Hodges of The Point Church in Kearns believes the earlier movement was more effective.

Its leaders were black Christians who were "deeply wrapped up in their spiritual, God-given rights," Hodges says. "For them, church and justice were the same."

Not so with Black Lives Matter, he says, adding that he wouldn't have that group in his church.

To Hodges, "all lives matter. Only the transformational gospel of Jesus Christ can change a person's heart."

King understood that to get to the "promised land" — racial equality — it would take more than just black people, Hodges says. "He was astute not to call it 'black rights,' so was able to harness the better angels of the entire citizenry."

The Rev. Nurjhan B. Govan, pastor of Utah's oldest black church, echoes that sentiment. King's forceful and evocative use of biblical language contributed to his success as an orator and leader, she says, and gave him "courage in the face of danger and adversity."

Black Lives Matter has become a "broad general movement, not church-centered, or God-centered," says Govan, of Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Church on Salt Lake City's Martin Luther King Boulevard. "With that, it loses some of its power."

The contemporary movement needs to be careful not to allow violence in its response, Govan says. "That would not be an emphasis if the pastors were at the forefront."

King is "our model," she says. "He taught passive resistance and nonviolence, but still urged people to stand up and be counted."

There are parallels between Jesus and King, Govan says. "They both gave up their lives for others out of love."

Twitter: @religiongal