This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

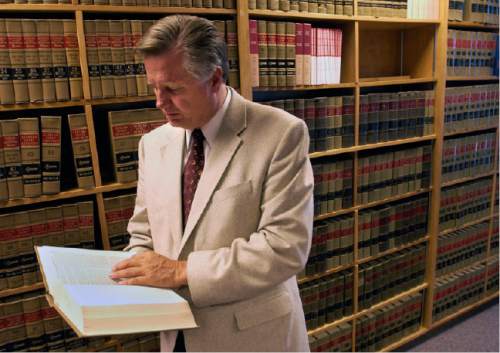

The catalog of Salt Lake County murder cases over the past 40 years has a single common thread: Deputy District Attorney Robert L. Stott.

From Ted Bundy and Arthur Gary Bishop to Ervil LeBaron, Joseph Paul Franklin, Ronnie Lee Gardner, Mark Hofmann, Mark Hacking and more.

"Pick the most historical cases you can in the last 40 years … he's there," said Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill. "Even in the cases that weren't the most prominent, he was in the shadows, helping."

Stott, 71, retired Friday after a 45-year career in law that many say leaves an unparalleled imprint on Utah's criminal justice system.

"It's been a life's work," Stott said during an interview in his corner office that overlooks downtown Salt Lake City. "I've made mistakes … but I got to help a lot of victims of crimes, you know, hundreds, thousands of victims of crimes."

The son of a steelworker and carpenter from Pleasant Grove who encouraged all of his five children to get an education, Stott fell in love with lawyering through the books, television and movies of his youth. The idea of standing before a jury and giving one's all for a client had strong appeal, he said. "At the time, I was a child of the '60s, so I thought, boy, these innocent people accused of crimes, and these cops and prosecutors who are out to get them ..." he said with a wry smile. "I wanted to defend."

After graduating from the University of Utah's law school in 1971 and clerking for a Nevada judge, Stott got his chance. He worked as a defense attorney for four years, representing clients accused of everything from jaywalking to murder.

"I can honestly say that there isn't a one of them that I am convinced was innocent," he said.

Stott has vivid memories of his first trial: a theft of cash from a service-station safe. The station attendant had allegedly absconded with the money in the middle of a night shift.

"The trouble of it was, he left a note. He left a confession," Stott recalled of his client. "And he wouldn't plead guilty, so of course it was an uphill battle."

He lost. Afterward, Stott said, one of the jurors approached him in the hall and struck up a conversation.

"He said, 'It was your first case, wasn't it?' " Stott said. "What I learned was that in cases like that, I've got to do something other than go to trial. You've got to something that's more favorable for your client."

By the mid-1970s, with his idealism worn a bit thin, Stott came home to Utah and a job with the county attorney's office, where he learned other important lessons from his first prosecution: Sometimes the facts change, and witnesses are not always right.

The witness in the case — an aggravated robbery at a convenience store — had confidently pointed to the alleged perpetrator during a preliminary hearing and said from the stand: "That's the guy that stuck a gun in my face," Stott recalled.

Weeks later, an investigator told Stott that a case had arisen in another jurisdiction with eerily similar facts. After scrambling together a "six pack" of mug shots including the two separately accused men, the photographs were shown to the witness. She chose a different man than she had pointed to in court.

"So I had to dismiss my first case," Stott said. "I realized that my job as a prosecutor is not just to win cases, my job is to win cases against the actual perpetrator of the crime. My job is to do justice."

Soon after, Stott was assigned to assist in the prosecution of Ted Bundy, who was accused in the 1974 kidnapping of Carol DaRonch. The case, which ended with Bundy's conviction on kidnapping and assault charges two years later, opened the door to other high-profile cases, he said.

Stott became the go-to prosecutor in murder cases, including capital crimes that carry the death penalty. Stott says he was drawn to the cases because of the interesting nature of the crimes and the legal intricacies and issues they present.

"They were all very complicated, they all took a lot of focus and they all had their particular draw," he said.

Stott counts the Mark Hofmann case as his most memorable. A forger who drafted counterfeit documents from Mormon history, Hofmann killed two people in 1985 with homemade pipe bombs delivered in packages when his scheme began to unravel. The case was full of intrigue and required innovative investigative work, including learning about paper, inks, printing and the value of historical documents, Stott said.

It was also a crime that terrorized the community unlike any other.

"During that time, there was great paranoia in the community," Stott said. "Nobody picked up a package."

The case also left many split on whether Hofmann could really have committed the crime.

"It was kind of our O.J. Simpson case here in Utah," said Stott. "But once we showed that he was a forger, he was a scoundrel, he was a flimflam man, then they could believe he could be a murderer."

Charged with capital murder, Hofmann pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree murder and two counts of fraud and is serving a life prison sentence.

Stott says his success in the courtroom is not the product of any particular set of skills or smarts, rather just hard work. That, he says, he learned from the defense attorneys he battled in court, who he realized might best him.

"I was amazed at the caliber of the defense attorneys," he said. "I thought the only way I was going to be successful was to able to outwork them, to be more prepared. So that was my goal."

Defense attorneys say sparring with Stott in the courtroom always made them better lawyers. His preparedness, command of the facts and intelligence requires the defense to work equally hard, said Ed Brass, who has squared off with Stott more times than he can count.

"You learn from him by what he does," said Brass. "He's honest. He's straightforward; there's no hiding things. You know what you're going to get, and that's someone who's very committed to their side of the case.

Although he's known for his steady, somewhat understated courtroom demeanor, Stott also has a knack for connecting with juries with passion and emotion.

"He's likable, and juries like him. He's effective, he's very bright and he knows the law," said Brass. "And it's not personal with him. He is the epitome of civility and courteousness."

Ron Yengich, who defended Hofmann, agrees. He credits Stott's good judgment and "moderating influence" with helping to resolve the case, saving the victims and families on both sides added and unnecessary pain.

"I think he epitomizes what a good prosecutor should be," said Yengich."He has always understood that prosecutors have a lot of power and that being a prosecutors requires you to exercise that power with good judgment and, on occasion, with great mercy."

Stott's retirement is a big loss for the district attorney's office, Brass adds.

"Bob is one of a kind," he said. "You don't often find people who are that good, that decent and, at the same time, that effective at their job."

Stott's legacy lies not only in his record of successful cases, but in the way he's mentored young attorneys throughout his career, 3rd District Court Judge Mark Kouris said.

"He's probably trained half of the criminal lawyers in town," said Kouris, who worked at Stott's side when he was a young prosecutor. "I followed him everywhere he went."

Third District Judge Ann Boyden, who also worked with Stott, said she can immediately recognize Stott-trained attorneys when they appear in her court. They are prepared, accurately state the law and apply it to the argument in the same old-school way their teacher would, she said.

"Many teachers allow students to learn to swim, yet stay close enough to keep them from drowning," she said. "Bob teaches his attorneys to swim, but he also gives them the tools necessary that no one has to save them." As good as Stott is as a lawyer, he's an even better person and friend, Boyden and Kouris said.

"He's completely loyal and nonjudgmental," said Boyden. "Over decades, I observed there was nothing he would not do for his wife and kids, and when I became very ill a few years ago, I learned there was nothing he would not do for a friend."

Stott has always extended that same brand of kindness to the families of murder victims, helping them to navigate the ups and downs of the criminal justice system, Kouris and Boyden said.

"He'll sit down with them and explain the options, and even though he's saying the same thing he's said a million times to a million other families, he makes them feel as if this is the first time," Kouris said.

Despite the difficulty of those conversation, Stott said he has enjoyed working with the families of the victims.

"I've really been impressed by some of these people; they have a great resilience," said Stott. "They have gone through probably the most horrific experience, but somehow they are able to overcome. They never forget it, and there's always in their hearts some sort of agony, but they don't let it overwhelm them and they don't let it define them."

In retirement, Stott said he and his wife, Deanie Stott, plan to spend time with family and travel. They also hope to serve a service mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Retirement brings a set of mixed emotions, Stott said. He still loves the law, but he admits he's lost some of the drive that's needed to delve into the kind of big, high-profile cases that have defined his career.

He is grateful, he said, for the opportunity to do a job he dreamed of and loved, for the experience of battling other attorneys in the courtroom and for the lifetime of friendships he's made.

"You hope, you know, that you get to like what you do and feel like it means something to your community," he said. "And as a lawyer, you've got to feel like you are achieving justice. It's a nebulous word, but that's what I was looking for and I think I was successful."