This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • In this regular series, The Salt Lake Tribune explores the once-favorite places of Utahns, from restaurants to recreation to retail.

Farmington • The Heidelberg restaurant, located inside the historic Rock Mill, once ranked among Utah's finest dining establishments.

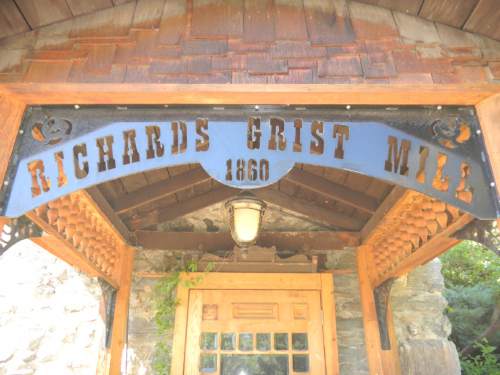

In the late 1960s, it was a place where couples got engaged or celebrated anniversaries or where high school students tried to impress their dates by dining there before or after their proms. From its secluded grounds in the Farmington foothills, where the mill was built of local rock and timber in 1860, the Heidelberg served German cuisine in an elegant three-story setting that included the century-old grinding stones.

When the original owners moved to San Francisco, new management trimmed the menu and the Heidelberg's popularity waned. But it left a legacy in another signature restaurant: a group who learned the trade there went on to open La Caille, offering French cuisine with a similar ambiance at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon.

The Heidelberg's original owners later returned but could not re-create its former glory, and it closed for good in 1989.

A savings and loan next owned the property, but when the institution failed, the mill and its seven surrounding acres fell into state hands. The restaurant and an adjoining center that had welcomed weddings and receptions fell into disrepair. Vandals tore the place apart inside and out.

That's where Tom Owens, the building's current owner, came into the story.

—

History in 'shambles' • Owens once worked as the producer of the "Death Valley Days" television series in Los Angeles, an experience that turned the Ogden native into a Mormon history buff.

He moved into Salt Lake City's American Towers in the 1980s and discovered Sam Weller's Books, then nearby on Main Street, and its trove of rare Mormon history books. He learned that the property where the Heidelberg was located was first owned by Willard Richards, the first historian of the Mormon church, who was with church Prophet Joseph Smith in 1844 when Smith was assassinated in jail in Carthage, Ill.

After members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints migrated into the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, Richards hired architect Frederick Kesler to construct a new mill in Farmington Canyon after an old lumber mill wore out. Richards died in 1854 and his nephew, Franklin D. Richards, took over the estate.

Kesler designed 29 mills in Utah, including Liberty Park's Chase Mill and the Farmington Mill, which was finished in 1860.

The 24-foot overshot wheel was the height of technology at the time. It used water diverted from Farmington Creek, but the mill soon became obsolete as the Industrial Revolution hit America.

According to Owens' records, the mill and building became Farmington's first electrical generator, its power used for Utah Gov. Simon Bamberger's railroad. Orchard owners used the cool mill to store their fruit. It also served as an ice storage house and then a home. In 1960, Garth Naylor and Terry Gross bought it and turned into the Heidelberg.

In 1992, Owens learned the property was going to be auctioned by the state of Utah, and he went out to take a look.

"It was in shambles," Owens said in an interview in 2012. But he could "see through the overgrown jungle and demolished stuff," he said, "... that this place had possibilities."

Fortified with a few belts of scotch before the auction, Owens won with a bid of $216,000.

—

'Ultimate antique' • Owens used the reception center for his advertising agency office while he lived in a two-bedroom cottage on the property. He stabilized the mill building, now missing its grinding stones, and then began to turn it into his own, a project that has become a labor of love.

"It's a great place to live," he said. "It is so private and isolated and such a historical property. ... The building and mill itself is the ultimate antique."

Owens hopes the LDS Church, the city, the county or a nonprofit will eventually buy the site. He has had chances to sell to developers, but their vision is to fill the grounds with homes.

"I am totally against that," he said. "If it were surrounded by tasteless McMansions, it would ruin it."

The mill "is the most important historical building in Davis County," he said, "and arguably the most significant LDS historical building in private hands anywhere."

Reviving the building as a restaurant doesn't seem feasible, Owens said, "because of the zoning and what would have to be done to make it a commercial building," including meeting earthquake codes.

So, for now, the building that housed the magnificent Heidelberg lives on as a home surrounded by open space, its history honored by a marker on the property.

If you have a spot you'd like us to explore, email whateverhappenedto@sltrib.com with your ideas.

Twitter @tribtomwharton