This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

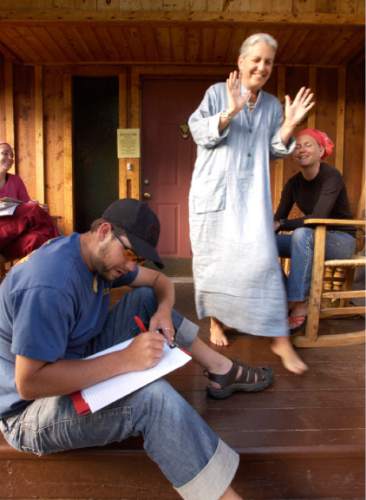

Terry Tempest Williams is leaving her University of Utah teaching post and walking away from the Environmental Humanities program she founded rather than agree to administrators' demands she move her teaching from the state's desert landscapes onto campus. "For reasons I will never know or understand, the University of Utah wanted me gone — and in the end, what was most threatening was my teaching. Why? Because each of you and our current students are challenging the status quo, each in your own way with the gifts that are yours," the acclaimed author wrote in an email last week to about 80 current and past students of the U.'s Environmental Humanities graduate program.

Known as Utah's most eloquent homegrown voice for conservation, Williams helped launch what has become one of the U.'s premier educational experiences, connecting highly motivated students with the nation's most adventurous writers and artists. Now some are accusing university administrators of being more concerned with procedural bureaucracy than with ensuring Williams continued her leadership. Williams' departure came as a shock to students, colleagues, program supporters, and at least one foundation, whose executive director said it would not renew a $50,000 grant awarded last year for Williams' "Reading the Book Cliffs" project. "We saw this course as a national model on how to engage people in new ways for critical issues, such as climate change," said Ellen Friedman of the Compton Foundation, which had premised its support on Williams' field teaching. "We are extremely disappointed." Williams' supporters are heaping criticism on U. administration for failing to find a way to keep her on faculty, and some suspect her environmental activism may have prompted the move to shackle her coursework to campus. Former student Alisha Anderson — who loved Williams' field course Art, Advocacy and Landscapes so much she took it twice, serving as a teaching assistant both times — said she was troubled by Williams' exit and what it portends for the program's future direction. "She has been a huge blessing in my life," said Anderson, who now works for Torrey House Press on community outreach. "Terry and the way she teaches was transformative. At universities there is inertia to change, and Terry was pushing the boundaries. How can we not integrate the land in how we learn?" Utah Film Center founder Geralyn Dreyfous and Karen Shepherd, a former congresswoman who represented Salt Lake City, resigned their seats on the College of Humanities advisory board in protest this week. — Williams said she decided to leave after six weeks of "humiliating" contract negotiations in which new Humanities Dean Dianne Harris and Amy Wildermuth, associate vice president for faculty, pressured her to accept a phased retirement and pay concessions. Administrators made it clear her contributions were no longer valued, telling her she "was paid too much for too little," she said. Her compensation package, including health benefits, is worth $95,700, according to public salary database Utah's Right to Know. After a deal was reached and Williams agreed to sign a new contract, administrators added one more demand April 16. Her practice of taking students into the deserts of southern Utah and the Wyoming's Tetons did not comply with university guidelines, exposing the school to liability and "engendering resentment" from students who might not want to travel. "It was at that point, I realized what the university fears most is empowered students, students tutored by the land itself, especially in Utah's erosional landscape of red rocks and rivers, and a bitten horizon that redefines time," Williams said in an email to the Tribune. "I can no longer work in an institution or program that privileges compliance over creativity, that values the language of bureaucracy over relationships and respect, and that is more concerned over issues of insurance than the assurance of emancipatory curriculum that benefits our students," she wrote in an April 25 letter to Wildermuth. "My fear is that universities, now under increased pressure to raise money, are being led by corporate managers rather than innovative educators." Wildermuth denied the university insisted on early retirement for Williams, who is 60. "We really tried hard to come up with terms that were within university requirements and have Terry remain part of our program. We still want her to be part of it. We haven't closed any of our offers," said Wildermuth. "It is truly unfortunate. We are so grateful for what she has done. We will miss her. She is a tremendous asset to our university." — A naturalist and author of a dozen books about western landscapes and their impact on the human spirit, Williams is Utah's most decorated writer since Wallace Stegner. Her latest book is "The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America's National Parks." Williams' association with the U. dates back to her undergraduate days in the 1970s and later as education curator at the Utah Museum of Natural History from 1986 to 1996. The U. awarded her an honorary doctorate in 2003 and she delivered the commencement address on her signature concept, "the open spaces of democracy." That was also the year she co-founded Environmental Humanities with then-Humanities Dean Robert Newman. Williams has been serving in the department as the Annie Clark Tanner Fellow under an endowment provided by philanthropist Carolyn Tanner Irish, the retired bishop for Utah's Episcopal diocese. The two-year Environmental Humanities program, which accepts eight students a year and graduates eight with master's degrees, explores the use of art and words to document the Earth's changing landscapes from numerous perspectives. Recent guest lecturers included scientist-turned-artist Subhankar Banerjee, anthropologist Wade Davis and Wyoming author Alexandra Fuller. The program is enjoying a record number of applicants, according to director Jeff McCarthy. "We have a more competitive group than it has ever been. The program is absolutely thriving," he said. "[Williams'] vision was key to success of the program. She is beloved mentor for scores of students." Williams' supporters say she has attracted high caliber students, guest lecturers and funders to the program. They contend that her in-the-field teaching style exemplified the program's stated mission to "integrate our need to know with our desire to act." Another aim of the program is "to encourage creative and collaborative exchanges both inside and outside the classroom." Williams is "a national treasure," said Dreyfous, a filmmaker who helped her teach field courses and land the Compton grant. "She is the Rachel Carson of our times. Her papers are in Yale's collections next to Carson's because the U. wasn't smart enough to ask for them."

But some of Williams' papers had been at the U.'s Marriott Library for 20 years following the author's move to Castle Valley, according to special collections manager Gregory Thompson. The material later became the subject of serious negotiations and a bidding war with Yale ensued. "The price was big-time six figures. We weren't able to raise the money quickly enough," Thompson said.

Yale came up with the money and received the material about five years ago. — University administrators first notified Williams that her contract needed changes in late February, less than two weeks after she and husband Brooke Williams bought an oil and gas lease as an act of protest against federal policies that promote what they believe is irresponsible energy development in Utah's sensitive landscapes. The couple said they intended to incorporate the 1,120-acre lease into the Environmental Humanities' curriculum, bringing students there to explore the land's values that would be compromised by drilling, while honoring federal laws governing how such leases are managed. "Our purchase was more or less spontaneous, done with a coyote's grin, to shine a light on the auctioning away of America's public lands to extract the very fossil fuels that are warming our planet and pushing us toward climate disaster. Out here in the Utah desert, we are hoping to tap into the energy that is powering the movement to keep fossil fuels in the ground," she wrote in a March op-ed published in The New York Times. Administrators say neither the Williamses' gesture, which angered Utah's political brokers, nor their activism, has been raised as an issue. Instead, Wildermuth said, the impetus for adjusting Williams' contract arose from a need to align the terms of her employment with university human resources and travel guidelines. "It was something we require of all instructors," Wildermuth said. "It's paperwork, arranging a university van for things. It is going through that hurdle. You still have to make sure you are not going to do things that would expose us to liability. We tying to have students not travel in private cars to these far-off places. We are making sure we are doing thing as safely as we can." Administrators emphasized that the course could still have a field component, but Williams believes they are interfering with when, where and how she teaches. "A line was crossed" that made it impossible for her to sign the contact, she said. "I have loved this program will all my heart and it has been a privilege to be part of it. A community of smart and passionate people has been created in the name of engagement. Our students have been my greatest teachers and they continue to inspire me," she wrote in her April 25 letter. "Our students are not only engaged in the world, they are changing it with their courage, imagination, and joy." Anderson and fellow Environmental Humanities graduate Michael McLane say they continue learning from Williams, even from her final act as U. faculty. "One thing she taught was when everything else is falling apart you always have one thing and that's your voice," McLane said. "The leadership of the school has stood silently by while this is going on, and that's a terrible example to set." bmaffly@sltrib.com Twitter: @brianmaffly

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713. Twitter: @brianmaffly