This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

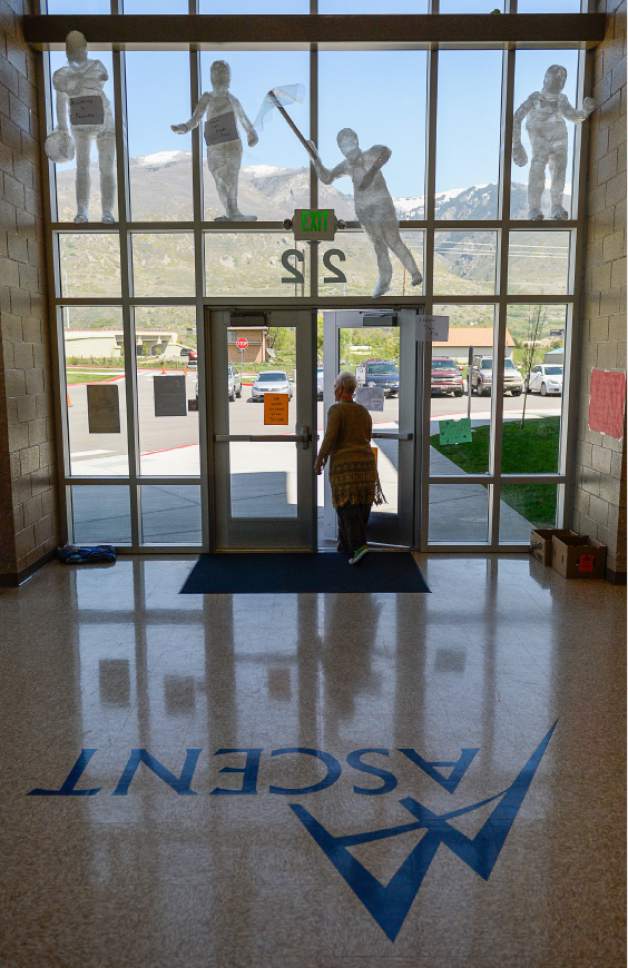

Farmington • When 75 mph winds swept through northern Utah this month, Ascent Academy was left with broken windows, a damaged fence and no power.

"We couldn't hold school, and the servers were all down," said Lani Rounds, the charter school's principal.

For help, Rounds turned to Academica West and Eminent Technical Solutions, which went to work filing insurance claims and patching up the school property.

The next day, classes were in session, and Ascent Academy was back on its feet.

"If I didn't have anyone to rely on, I don't know how I would have pulled yesterday off," Rounds said. "I worked, and everybody else did their thing, and we were up and running later in the afternoon."

Public schools of all types regularly direct money toward private businesses — like software companies, food-service distributors and textbook publishers — for specific services. But Ascent Academy and many other charter schools take it a step further, abdicating administrative and academic functions to private companies.

Academica West and Eminent Technical Solutions aren't simply ground-maintenance companies — they function as the information technology and human resources departments for Ascent Academy and 16 other charter schools, which on paper are their own school districts.

Together, the two companies received at least $6.9 million from charter schools last year, according to a Salt Lake Tribune analysis of charter-school expense reports.

Though these and other private charter-management companies receive public education funds, they do not have to disclose how they spend their money. And any surplus funds are collected as profit rather than returned to the schools the company serves.

—

Public information • In some cases, it's unclear where a charter school ends and the private company begins.

The 2013 expense report for online charter school Utah Connections Academy shows a single item — $2.6 million to Connections Education, the Maryland-based company that operates the school.

And at Utah's five American Preparatory Academy campuses, school administrators are not school employees. Instead, they work for American Preparatory Schools, a Draper-based company that charges roughly $900 per student — more than $4 million in 2014 — to provide comprehensive management of curriculum and operations, according to Carolyn Sharette, the company's executive director.

Though there have been persistent rumors, Sharette said that she and other service providers do not collect million-dollar salaries by privatizing public education. Her company's books are open — with the exception of individual salaries — to anyone who asks and they show there's no excessive gain.

"If a school-management company is able to provide that richness of programming in the lowest-funded state in the country and still find profit," Sharette said, "then perhaps they shouldn't be criticized. Perhaps we should be delving into what on earth they are doing to be able to do it."

Kim Frank, executive director of the Utah Charter Network, said there is a place for management companies in the charter school system, but she prefers smaller, specialized firms to the comprehensive service providers that assume school operations.

Transparency questions are valid, she said, and the public is right to expect to know how education funds are spent.

"A lot of people question, whether it's true or not, that they're hiding something," she said. "What have they got to lose? Open the books and let the public see what is in there."

—

Follow the money • Royce Van Tassell, executive director of the Utah Association of Public Charter Schools, said the state has a long history of partnering with private companies on public services, and he compared charter-service providers to contractors who pour concrete for Utah's roads.

"I just don't see anything terribly remarkable about any of these relationships," he said.

But several of Utah's highest-earning charter companies are owned by or employ current and former state lawmakers and their family members, leading to frequent accusations of bias as legislators direct state resources to school-choice alternatives.

Three years of expense reports analyzed by The Tribune show that several private companies regularly receive millions of public dollars for the services they provide to some of Utah's 100-plus charter schools.

Those records were prepared by school administrators or on their behalf by Van Tassell. All numbers are estimates, as inconsistencies and incomplete data from individual schools make precise calculations unlikely.

Besides American Preparatory Schools, the highest-earning companies were:

• A Plus Benefits, which received more than $25 million in 2013 and 2014 and $3.3 million in 2015 from between four and 12 charter schools, depending on the year. A company spokesman said the bulk of those funds was paid to school employees through payroll services.

• Connections Education, which received $4.3 million in 2014 and $5 million in 2015 from Utah Connections Academy.

• Harmony Educational Services, founded by former state Sen. Rob Muhlestein, which received $6.4 million in 2013 and $5.5 million in 2014 from roughly 10 charter schools.

• Virginia-based K12 Management, which operates one Utah school, Utah Virtual Academy, for roughly $4.5 million each year. K12 Management is represented in Utah by Stacey Hutchings, Utah Virtual Academy's head of school and wife of Kearns Republican Rep. Eric Hutchings.

• Academica West, which received roughly $3 million in 2013 and 2014 from 13 schools before climbing to $4.7 million from 17 schools in 2015. The company's president, Jed Stevenson, is the son of Layton Republican Sen. Jerry Stevenson. The company's vice president is Sheldon Killpack, who resigned as majority leader of the Utah Senate in 2010.

Another state senator, South Jordan Republican Lincoln Fillmore, is president of Charter Solutions, which receives more than $1 million from roughly 15 charter schools each year.

And Sharette, of American Preparatory Schools, is the sister of Howard Headlee, president of the Utah Bankers Association and chairman of the state Charter School Board.

Stacey Hutchings said she and her husband are careful to avoid activities that could be seen as conflicts of interest.

His position on the House Education Committee requires him to debate and vote on school bills, she said, but she doesn't lobby him on issues that specifically affect her charter.

"He has his work and I have mine," she said. "We keep it pretty separate."

Trent Brown, an operations director at Academica West, said it's common for industries to be represented by the part-time lawmakers on Utah's Capitol Hill.

"I would venture to say lots of successful businessmen are well-connected up there," he said. "That's not unique."

—

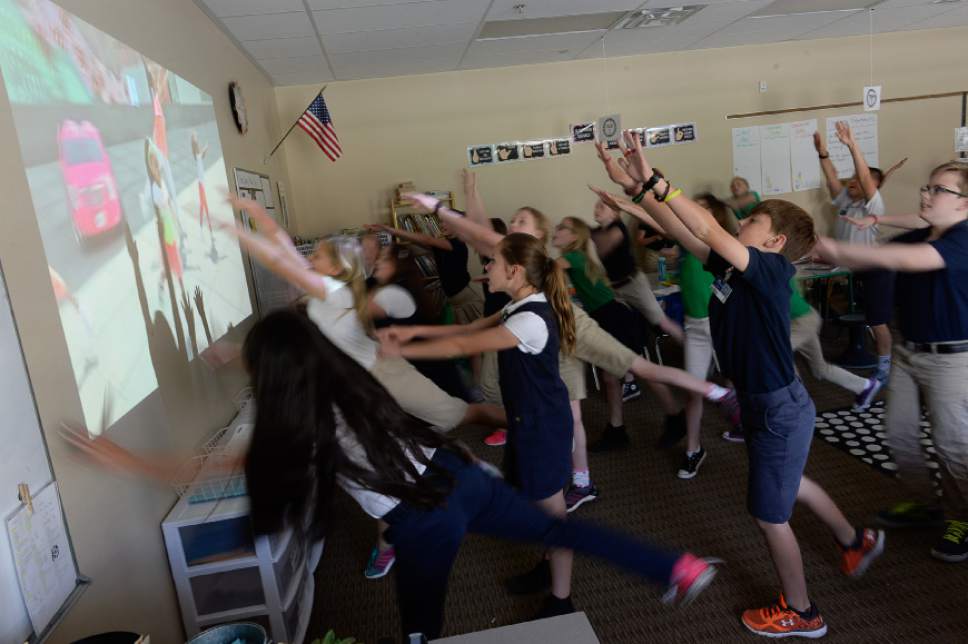

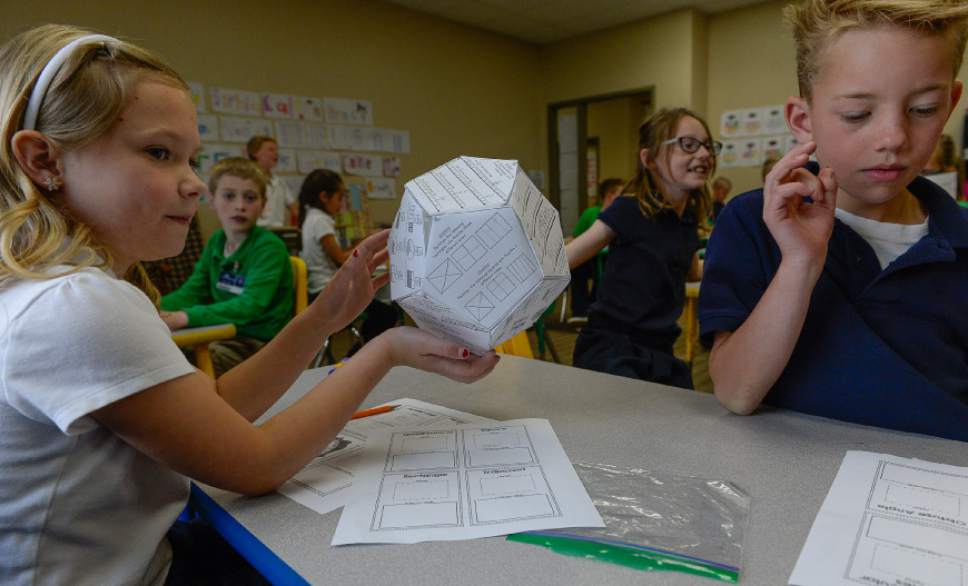

Specialized education • Charter companies say the outsourcing of business tasks to businesses allows educators to focus on education.

"The principal becomes the educational leader of the school," Brown said. "We pick up all the rest of the stuff and try to take as much as possible off their plates."

For many charters, Brown said, the cost of hiring Academica West is also cheaper than building office space and paying the salary of an administrator.

"Pretty much whatever your [school] district offices are doing," Sharette said, "I would say that we have the same thing."

With 3,900 students, the American Preparatory Academy network is comparable in size to rural districts like Carbon School District and Sevier School District.

Even without the economies of scale in Utah's larger, urban districts, Sevier Superintendent Cade Douglas said, it wouldn't make financial sense to hand administrative duties to a private company.

"There's no way that we could afford that," he said.

Beyond the finances, he said, he prefers the local oversight of his administrators, who wear several hats in the district office and are familiar with Sevier County and its residents.

"By having people that know our system, our goals, our students and our culture," he said, "I think we can save time and make better decisions by keeping it in-house."

Charter schools were intended to be more independent than traditional schools, Frank said — in some cases, grass-roots projects led by parents.

By moving away from individual charters toward school networks overseen by corporate firms, she said, charters lose the qualities that make them distinct.

"Charter schools ought to be unique and meet the needs of their specific community," she said, "and not just look and quack like all the other ducks."

—

No complaints • Lawmakers this year approved a funding bump of $20 million to charter schools.

But Academica West's Brown said more cash in charter coffers doesn't necessarily mean higher profits for service providers.

His company charges a per-student fee, he said, equal to $400 for a school's first 500 students and $350 after the first 500.

In return, the company assumes the bookkeeping and human resource functions of the school, while also providing facility maintenance and a team of education consultants.

"When the $20 million hits those charter schools that are affiliated with us," Brown said, "it's going to go straight to the charter students and the teachers."

Brown said some people will always be skeptical of outsourcing education, but the success of charter partnerships are evident in the success of charter schools.

"If we were charging way too much money, our schools would be struggling and living in a Tuff Shed," he said. "But they're not. They're in incredible facilities, and there's money in the bank."

If there were widespread concern about charter finances, Van Tassell said, the public would make that known.

"When folks are relatively quiet, it's one measure that there is a degree of trust and things are working out," he said.

But political unrest remains over how charter schools should be supported, regulated and funded.

A legislative task force was created last year to study disparities between charters and districts. At one task force meeting, a Democratic lawmaker suggested that ending charters outright would solve lingering questions.

If that happened, the revenue for companies like Academica West would be wiped out.

"If charter schools vanished, we'd be looking for jobs," Brown said. "All of our clients are charter schools."

Despite the recent wind damage, Ascent Academy administrators see clear skies ahead.

The Ascent Academy network currently includes three campuses, with plans to open a fourth in West Valley City, according to director Wade Glathar.

Before that expansion, Glathar said, Ascent plans to add three network administrators who aren't assigned to a single school.

Glathar said there are no plans to hire internal staffing to replace Academica West and Eminent Technical Solutions. And he said it's unclear how many campuses the Ascent Academy network would need for that switch to make financial sense.

"As long as it's working I don't need to fix something that isn't broken," Glather said. "It's working well. [Parents] are not going to start asking questions, per se, when things are going well."

bwood@sltrib.com Twitter: @bjaminwood