This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Weather has gnawed away at City Hall's stone faces each of the 27 years since its last makeover, but there's a bigger worry in the basement.

New earthquake modeling indicates a once-innovative system of rubber couplers underneath the Salt Lake City-County Building might not protect the architectural treasure as intended — in light of evidence "the Big One" will likely be larger than scientists thought decades ago.

Extensive work begins in the coming weeks to fix both problems. Starting June 6, crews will wrap scaffolding around the public facility at 451 S. State as they start a stone-by-stone remediation of its exterior, while others cut an opening on its south flank to get at the 122-year-old foundation.

All told, upgrading seismic safeguards, replacing and repointing many of City Hall's Utah Kyune sandstone features and repairing exterior window trims will cost about $8.5 million and take three years.

"The care of this facility is paramount to us," said Alden Breinholt, director of the Operations Division of the city's Department of Public Services, who, along with various City Council members, has made the overhaul "a pet project" for nearly 11 years.

Calling the work essential, given the building's historic significance, Mayor Jackie Biskupski's office noted the government seat would remain open to business for the duration of construction. Events on the grounds of Washington Square also will be accommodated as usual, said Matthew Rojas, director of communications.

Meshing with Biskupski's recent budget focus on improvements to city facilities, roads and utility lines, planning for the City Hall refresh began with studies in 2008 and 2012. Money was set aside in 2014, and the project has been reviewed by Utah Heritage Foundation and the city's Historic Landmark Commission.

Built between 1891 and 1894 in a quirky Richardsonian Romanesque style — and decorated with gargoyles, sea monsters and symbolic statues of Justice, Liberty and Commerce — the landmark boasts a rich history. It served as the state's constitutional convention hall, offices for state, county and city governments and as the venue for labor organizer Joe Hill's infamous trial.

The ornate brick building and its sandstone base also have proved vulnerable to several earthquakes produced by the many Wasatch Front faults.

A 1934 magnitude 6.6 quake centered 80 miles away in Utah's Hansel Valley shook clock equipment loose from the City-County Building's tower and sent it crashing to the ground, along with large sheets of interior plaster. Smaller temblors have braided countless cracks into its gray walls.

Major seismic renovations to City Hall between 1973 and 1989 anticipated a magnitude 6.8 quake. Crews fortified it with crisscrossed steel beams, buttresses and other protections from below ground and through its five floors to top portions of its statued tower.

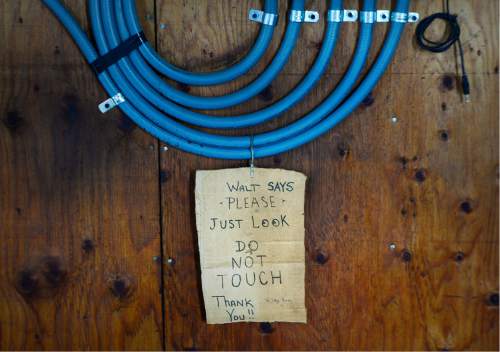

More crucially, workers sliced a gap between the building and its soft sandstone foundation and inserted 433 rubber-padded couplings, known as base isolators — reportedly a first for public buildings. The heavy black rubber isolators, some wrapped around rods of lead, are meant to cushion and let the building gyrate in a quake, minimizing permanent damage.

But, today, Utah's earthquake-preparedness experts agree the state is due for a magnitude 7 quake or bigger, based on data that the region's geology has produced temblors on that scale about every 300 to 350 years. Those few added decimal places pack a hefty punch.

A higher-impact 7.3 magnitude earthquake could displace City Hall by as much as 10 to 16 inches, studies show, while the base isolators were designed for a maximum shift of 14 inches. Breinholt said recent computer modeling in a California laboratory revealed the isolators might even roll instead of wobble through a quake that large, potentially dumping the building on its side.

Crews from the city's contractor, Big-D Construction, plan to lay concrete beams strategically around the isolators to serve as landing pads in case the rubber studs fail. Breinholt said that is expected to keep the structure viable in "a large event."

"It's a fail-safe," he said. What city employees call "the beautiful castle" still could suffer damage in a major quake, Breinholt said, "but it won't come down."

While earthquake work continues through mid-April of next year, crews will painstakingly repair delaminated stone facades and statuary on the exterior, beginning with the main and four lesser towers.

Based on a 2012 study that mapped every stone with drones, crews will also reappoint sections of washed-out mortar, pin loose stones into place, inject filler into cracks and mold metal flashing to some of the building's lines to better divert water.

Where needed, Breinholt said, original sandstone pieces quarried near Price will be replaced with a similarly hued Virginia limestone.

After the tower's face-lift is done, stone work on lower portions of the building will run between summer 2017 and fall 2018.

Having championed City Hall's aging needs for more than a decade, Breinholt tromped for the umpteenth time this week from its musty underground halls to its clock tower, keys rattling in his pocket.

"It's gratifying to see this project come to be," he said, gazing at the spires he has grown to love. "You just don't find this anymore."

Twitter: @TonySemerad