This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

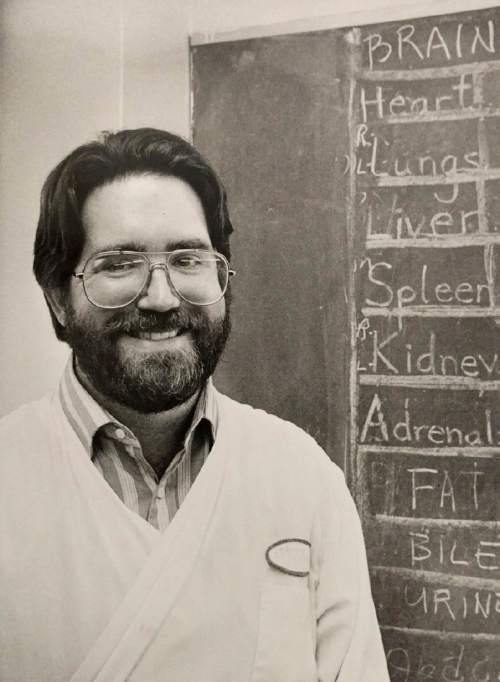

Utah State Medical Examiner Todd Grey sees two kinds of memorable cases.

There are what Grey calls the "Oh, my God" cases. "Those would be people who fall in large, industrial mixers," Grey said, giving one example.

Then there are the deaths that evoke empathy for the family. Grey recalled a boy who years ago complained of not feeling well, developed sepsis and died.

Grey conducted an autopsy, sent tissue samples to laboratories and read pathology texts. He eventually determined the boy contracted an infection from a bacteria that lives on cat claws. A cat had scratched the boy.

"Those are the cases that emotionally stick with you," Grey, 62, said Thursday at an open house celebrating his retirement. "It's sad and it's intellectually challenging."

After 28 years, Grey retired this week as Utah's chief medical examiner. He will remain in the office for a few more weeks to finish writing reports for autopsies he conducted and will testify in courtrooms about how some of the state's homicide victims died.

One of Grey's deputies, Erik D. Christensen, has been hired as the new chief.

Grey had been an assistant state medical examiner when, at age 35, he was appointed chief in 1988. He became Utah's fifth chief medical examiner in six years as a succession of pathologists complained the pay was too low and the whole office was underfunded.

Those concerns never went away, though Grey on Thursday said the office's finances are better than they used to be. Year after year, Grey has asked the Utah Legislature for more money. His retirement leaves the office with just four forensic pathologists to conduct about 2,800 autopsies a year.

The office is trying to hire four more, but even in an era where medical examiners have gone from obscurity at the back end of epidemiology to the subject of television shows, qualified candidates are hard to find. Grey, who went to medical school at Dartmouth College, said forensic pathology requires as much training as some surgical specialties and pays one-third as much.

Investigators in the medical examiner office also determine the cause of death for another 5,000 to 6,000 Utahns a year. A delay in those investigations, Grey has told the Legislature, means a delay in issuing death certificates. And insurance companies won't pay death benefits to heirs until there's a death certificate. The caseload also has prevented Utah's medical examiner office from obtaining a national accreditation that most medical examiners have.

"Too many cold bodies for too few warm ones," Grey said.

Though busy, Grey found time to sound alarms.

In the '00s, using data collected by his office, Grey reported an epidemic of overdoses from prescription pain relievers. The numbers, and Grey's urging, spurred the Utah Department of Health to begin a campaign called Use Only as Directed.

More recently, Grey informed public health officials about increases in some suicide rates. Robert Rolfs, the deputy director of the Utah Department of Health, noted Grey's empirical work Thursday in addressing attendees at the open house, saying Grey and the other medical examiners in the office served as the public's conscience.

"Utah is a better place because of the work you've done," Rolfs told Grey.

When homicide was suspected, Grey was willing to collaborate with police, said Todd Park, a Unified Police Department homicide detective who attended Grey's farewell.

When Park reopened the 1974 murder of Barbara Jean Rocky, a 21-year-old Brigham Young University student whose body was found with bullet holes in Big Cottonwood Canyon, he and Grey met to review the original autopsy report and discuss potential new evidence.

"He was always very approachable and willing to help out in those cases," Park said.

Gerald W. Hicker admitted to shooting Rocky and pleaded guilty to second-degree felony manslaughter in 2009. He was sentenced to up to five years in prison.

Salt Lake County Deputy District Attorney Vincent Meister said Grey did a good job of explaining anatomy and medicine to jurors. He neither patronized them nor assumed they knew certain terms, Meister said.

"It wasn't pro-prosecution or pro-defense," Meister said. "The facts were the facts."

Courtrooms also gave the public a chance to see Grey and his perpetual affability. On the witness stand, he would smile and greet veteran prosecutors and defense lawyers with a, "Nice to see you again."

Grey will remain in Utah and work as a consultant. His wife, Lorraine B. Szczesny, is a doctor of internal medicine in Salt Lake City. Their son, Cameron, is a graduate of the University of Utah's video game program and now designs games. Their daughter, Jessica Grey, is attending medical school at the U.

Twitter: @natecarlisle