This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Land-use plans for four of Utah's five national forests are at least 30 years old, prompting federal land managers to revise them — but some state and local officials worry this is a cover for advancing an agenda to do away with grazing, close roads and designate wilderness.

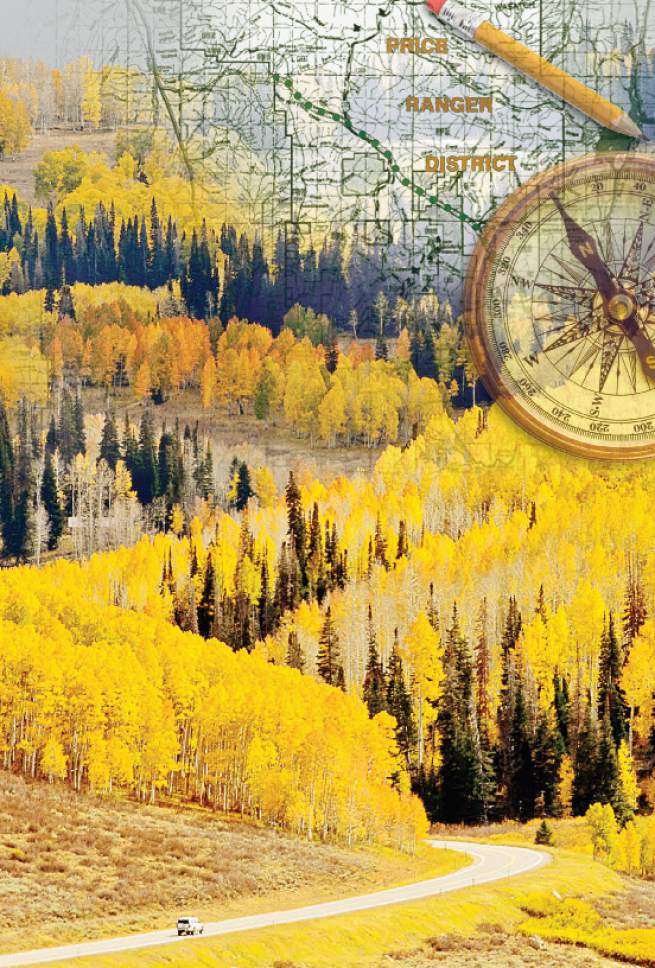

Forest managers — who've started with the far-flung Manti-La Sal and the Ashley — say that their process is open and transparent, and that the plans are in dire need of updating. Recent decades have seen the decline of aspen forests; beetle infestations that have left entire stands of spruce dead; historic shifts in the coal, timber and livestock industries; and the proliferation of motorized recreation.

"This establishes strategic frameworks for management of the forest to allow multiple use for the next 15 years," said Blake Bassett, planning coordinator for the Manti-La Sal. "We are stewards of a precious resource, and we want to know how the public wants them to be managed. One interest group is not going to outweigh another."

Lawmakers last month grilled forest supervisors John Erickson of the Ashley and Mark Pentecost of the Manti-La Sal about the U.S. Forest Service's intentions. Preliminary maps posted by forest officials show potential wilderness, leading some lawmakers to conclude these lands were being "proposed" for wilderness designation.

Officials responded that those maps are merely inventories of unroaded lands that the forests are required by law and policy to evaluate for wilderness recommendations under a new forest planning rule.

"We just had an inventory and people are worried we have an agenda for that and I understand that," Erickson told the Natural Resources, Agriculture and Environmental Quality Interim Committee. He urged people to help identify the improvements that have been installed on unroaded lands through the years. "That input will be valuable to determine whether it is even suitable for wilderness. Forest Service can't create wilderness; that's an act of Congress. I don't know what we will recommend — if anything."

State officials are skeptical.

"We are kind of groping in the dark trying to understand it. There is a degree of alarm because it is a different [planning] process," said public lands policy director Kathleen Clarke. "Our experiences with [the National Environmental Policy Act] is that once you see documents in print, it's hard to modify them. We feel that is very premature and they should pull it back until they hear the comments. The concern is, in many cases, we see access shrinking."

Clarke's concerns have cropped up at the recent open houses that the Forest Service held to engage the public on plan revisions, but drew unanticipated controversy.

At the Aug. 5 Monticello meeting, Manti-La Sal officials stumbled into a hornet's nest by holding it at the new Canyon Country Discovery Center, which has a conference center available at low or no cost for community events. Some locals say that the Forest Service's choice of venue shows that it's in league with environmentalists, though the town and San Juan County were early partners in the center.

At the Sept. 12 open house in Manti, one of the attendees signed in as a "domestic terrorist." No violence was threatened, but the log entry was reported to federal law enforcement.

Lawmakers also challenged forest officials about what they see as poor turnouts — the Forest Service open houses have so far attracted about 170 people for each forest.

"With all those meetings, 170 attendees is not a lot. We are a little surprised by that," said the committee's co-chairman, Sen. Scott Jenkins, R-Plain City. "It doesn't appear that you are getting the attendance at these meetings. It doesn't seem to be the word is getting out."

The Manti-La Sal hosted recent open houses in Mount Pleasant, which drew only three people, and in Provo, attended by 11.

Pentecost noted the Manti-La Sal has conducted extensive outreach and sent invitations to governmental entities, including 10 county commissions, seven water districts and seven American Indian tribes. Many of these will be able to participate in plan revisions as "cooperating agencies," meaning they will get to influence the plan in ways that conservation and other interest groups cannot.

Lawmakers sent a letter to the Ashley forest in late September asking it to delay its planning process to enable more people to participate. Though that forest is two months ahead of the Manti-La Sal, it's still in a preliminary phase of a four-year process, with numerous opportunities for public involvement still to come.

The next stage would be a draft assessment, which the Ashley expects to release in mid-November.

The Dixie will start its plan revision in 2019, and the Fishlake the year after that. The Uinta-Wasatch-Cache revised its forest plan in the early 2000s under the old planning rule.

Plan revision covers 15 topics, including grazing, climate change, biodiversity, wildlife, travel management, recreation and water. Wilderness, a perennial flashpoint in Utah's public lands controversies, has drawn the most concern.

Officials emphasized that wilderness recommendations entail a four-step "iterative" process that pares down wilderness-quality lands to a short list.

"It has to be an unbiased, methodical approach," Bassett said. "A good way to think of the process is as a series of screens, with the first screen having large gaps through which boulders could fit. With each successive phase, the gaps in the screens get smaller and smaller until there are only pebble-size gaps."

The 1.4 million-acre Manti-La Sal stretches in four noncontiguous units from Spanish Fork Canyon in the northeast to Bears Ears Buttes, the twin peaks that anchor the controversial national monument proposed for southeast Utah. Nearly half the forest, 645,000 acres, is inventoried roadless. The 47,116-acre Dark Canyon Wilderness is the only designated wilderness on the forest, and conservationists believe many other areas are worthy, starting with untrammeled alpine reaches of the La Sal and Abajo mountains.

"Throughout the forest, there are wilderness-quality lands worth considering, but the Forest Service is really far from making an actual recommendation and whatever they recommend, given the politics in Utah, will not likely result in a designation," said Tim Peterson, Utah wildlands director for the Grand Canyon Trust. "These concerns are misplaced because these plans don't make decisions on the ground. Wilderness has always been citizen driven, especially in Utah."

The Ashley covers a landscape that bears little resemblance to the southern Utah forests. It is a largely contiguous 1.4 million-acre block, spanning the Uintas, Utah's largest and highest mountain range. It includes the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area that reaches into Wyoming. About 70 percent of the forest is inventoried roadless and wilderness, namely the 457,000-acre High Uintas Wilderness. It is larger than all of Utah's other wilderness areas combined — and many county commissioners aren't eager to see it enlarged.

This range harbors several historic reservoirs with aging dams, but their presence inside designated wilderness complicates maintenance operations since crews can't drive to them. Equipment and materials needed for repairs must be brought in by helicopter and pack horses.

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly