This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The bristlecone pine is not only the world's longest-lived organism, but it is also virtually immune to the pine beetle attacks that are decimating conifer forests around the West, according to new research from Utah State University and the U.S. Forest Service.

In a study released this month, researchers concluded that the properties that help individual trees survive for up to 5,000 years on wind-hammered alpine ridges may also serve these pines well in repelling the beetle outbreak that scientists attribute to a warming climate.

"Bristlecone grows in these extreme harsh environments. The ability to grow here and live a long time is enhanced by having high resin and dense wood. That happens to help against beetles," said Barbara Bentz, an entomologist with the Forest Service's Rocky Mountain Research Station in Logan. In prior studies, Bentz has documented that a pattern of increasingly mild winters has allowed pine beetles to survive from year to year in lower elevations and complete their reproductive cycle in a single year.

Bentz and colleague Karen Mock of USU's Department of Wildland Resources were intrigued by growing tree mortality, apparent in aerial surveys in high-elevation areas in the Great Basin mountain ranges between Utah and California. When explored on the ground, these stands told an interesting story: Limber pines were suffering from the phloem-eating beetle, but bristlecone growing in their midst were largely unscathed.

Their inquiry builds on a study published last year by USU graduate student Curtis Gray and colleagues who observed beetles' behavior after exposing them to volatile compounds released by various pine species. They were capturing volatiles off unmolested bristlecone pine high in Nevada's Cave and Spring mountains when they noticed nearby stands of limber pine had been ravaged by beetles.

So Gray gathered volatiles off both species to conduct his lab experiments. His team encased the trees' foliage in a bag and pulled air through for 30 minutes, concentrating their volatile compounds into 3-inch glass straws. They analyzed the chemical profiles of these compounds, then set up an experiment in which beetles were offered a choice from among limber volatiles, bristlecone volatiles and plain air.

"They would sit there with their little antennae and move them back and forth and decide which way to go. They always went to limber pine. If the choice was between plain air and bristlecone, they would more often go to plain air," Gray said. "They were attracted to certain compounds in the limber that were absent from the bristlecone. We strongly believe it is not one chemical. It is the combination and ratio of them."

Bentz's team set out to quantify beetles' impact on the various tree species found in the Great Basin's isolated alpine islands, then figure out what bristlecone has going for it.

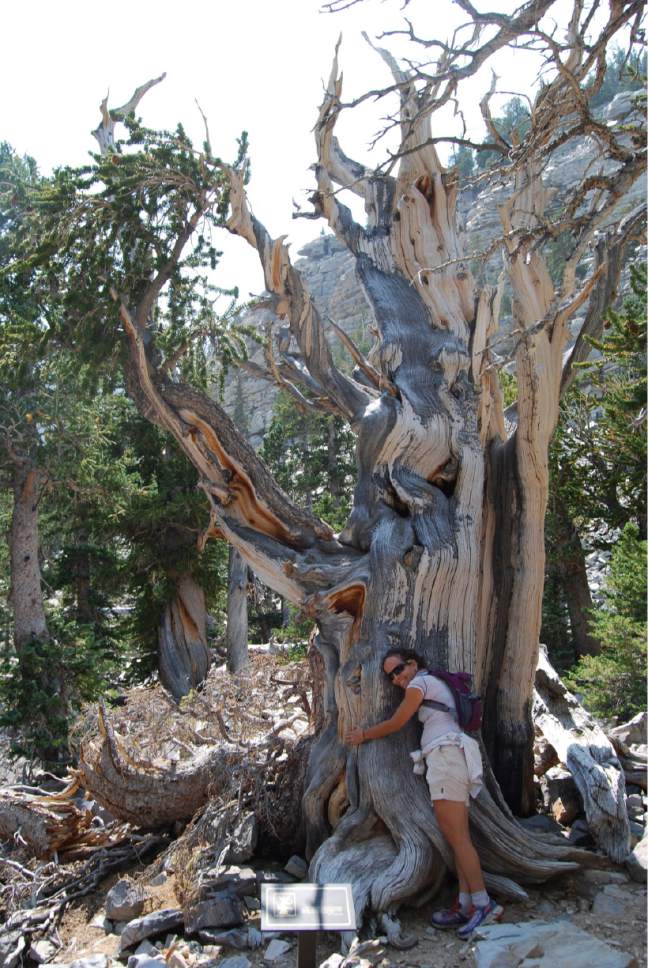

Researchers surveyed stands in various Great Basin ranges in the summer of 2014, from Utah's Cedar Mountains in the east, Nevada's Ruby Mountains in the north and the White Mountains to the west in California. They selected areas where limber pine and Great Basin bristlecone overlap and aerial surveys indicated severe tree mortality. With Gray's help, they identified sites that were also accessible by foot. These trees grow in steep rocky terrain between 8,500 and 11,500 feet in elevation, so they are difficult to reach, especially when you are lugging 50 pounds of equipment, Gray said.

Like other high-alpine pine species, limber and bristlecone have short needles that cluster in groups of five and can live for centuries clinging to exposed rocky outcrops. Whereas the oldest bristlecones are 4,000 to 5,000 years in age, limbers top out at around 1,000 to 2,000 years. The oldest known limber pine is at least 1,700 years old, inhabiting Utah's Little Cottonwood Canyon.

Bristlecone comes in three species whose ranges do not overlap: Great Basin; foxtail pine, found in the Sierra Nevada; and Rocky Mountain, found in New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado.

Inside fixed-radius plots, Forest Service researchers Sharon Hood, Matthew Hansen and James Vandgriff examined every tree exceeding 5 inches in diameter, as well as every beetle-attacked tree in larger zones. Not one of the Great Basin bristlecones had been killed by beetles. In fact, hardly any had even been penetrated.

"We found maybe three or four out of several thousands where they tried to attack and there was no reproductive success," Bentz said. Meanwhile, the nearby limber pines showed mortality rates of 7.2 percent in the Schell Creek Range to 34.4 percent in the Rubies.

The team took core samples to analyze the wood itself for differences that could explain why beetles left bristlecone alone.

"Bristlecone had eight times the quantity of chemical defense compounds than limber in the same stands," Bentz said. And the quality of the trees' resins may also be a factor since the two species harbor compounds that were not present in the other's resin. The research also found bristlecone had more resin ducts and denser sapwood and heartwood.

Bentz and Mock suspect there is a complicated evolutionary relationship between beetles whose life cycles hardly last a year and trees that persist across millennia. One advantage bristlecones may hold is their ability to produce cones and seeds up until the end of their long lives, enabling it to project a genetic signal of resistance for a very long period

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly