This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

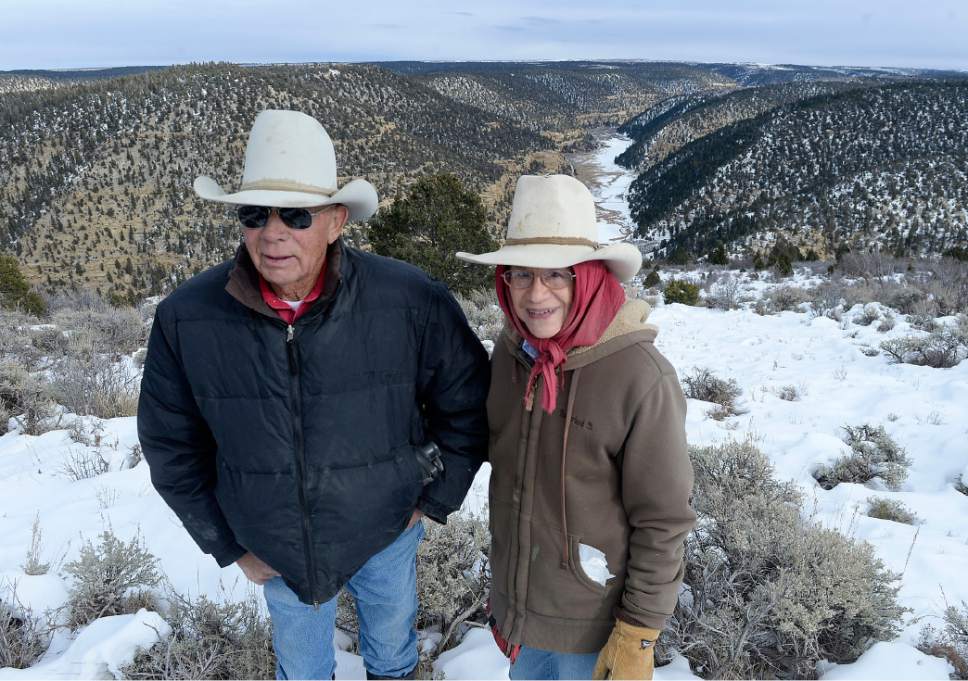

For 39 years, Burt and Christine DeLambert have operated their ranch in Main Canyon hidden in Utah's Book Cliffs where springs emerged from the ground. At least they used to, sustaining hay yields, hungry cattle and bison, and ponds loaded with fat trout, with enough water left over to sell to the oil companies drilling on the DeLamberts' land.

Main Canyon Ranch was a lush "Shangri-La" in the arid southern fringes of the Uinta Basin, but ever since an energy company began prodding PR Spring's tar sands deposits, the DeLamberts' water source has been disappearing, and the ponds have gone dry.

"We used to get 7,000 to 9,000 bales of hay out of that canyon. Last year I got 300, and this year I didn't even cut it. I don't believe there is hardly enough water for us to bring all those cattle back into the canyons now to ship them," Bert DeLambert said. "When they started drilling, that ruined that."

US Oil Sands, a cash-strapped Canadian firm developing state-owned minerals at PR Spring, has drilled 180 shallow cores as well as several deep wells in search of water. The first four wells were dry, but the company struck water as they moved west, across the Seep Ridge Road to the very edge of Main Canyon.

Looking over Main Canyon from the mesa top, one can't help notice how it is an oasis — a patch of green where the bone-dry East Tavaputs Plateau spills into the Roan Cliffs. It's no mystery to Bert DeLambert why the oil company's westernmost well was a winner. That's where the water is, and he thinks it could be his.

"What bothered me the most was they were supposed to stay on the east side of Seep Ridge Road, but they kept moving over toward Main Canyon. It's plain to see by looking into the canyon to see where the water is at," he said.

His big spring used to disgorge 50 to 60 gallons a minute, putting out enough water for a stream to reach Willow Creek, miles to the northwest. Now the spring's water won't reach the pond near the DeLamberts' home.

And US Oil Sands hasn't even begun mining. It has completed construction and equipment installation needed to begin extracting bitumen and processing it into oil, but it has run into troubles over financing and an incomplete state permit. Company officials last fall claimed that a water rights transfer, which the DeLamberts were contesting, was the last obstacle and that they expected to begin producing oil by the end of the year.

But now, company officials say, after spending $62 million on the project, financing shortfalls have pushed back the finish line on what would be Utah's largest mine tapping bitumen, the tarry ore that requires immersion in solvents to extricate hydrocarbons and turn them into liquid oil.

The company is temporarily mothballing the project, located 30 miles southwest of Bonanza in Uintah County, while executives work out a $7.5 million financing deal with a firm known as ACMO, US Oil Sands' largest shareholder.

"This has not been an easy period for all our stakeholders. We have made considerable efforts in sourcing additional capital and ultimately are fortunate to continue to have ACMO provide the financing," CEO Cameron Todd said in a Dec. 2 news release. "The decisions we have had to take have not been made lightly, as we know they affect many businesses and families."

Following that announcement, prices for US Oil Sands stock climbed 50 percent — from 2 cents to 3 cents a share. Company executives acknowledged that financial restructuring is no guarantee the project will get off the ground.

"Failure to secure additional financing may cast significant doubt about the company's ability to continue as a going concern," US Oil Sands wrote in a recent financial disclosure.

Still, executives are optimistic that they can realize their vision of producing 2,000 barrels a day.

The company's setbacks are little comfort to the DeLamberts, who brought their concerns to State Engineer Kent Jones in an unsuccessful effort to prevent the transfer of 360 acre feet of water from the Uintah County Water Conservancy District to the tar sands project. The ranchers believe the company's exploration and other pre-mining activity is impairing their long-standing water right, according to their lawyer, Gayle McKeachnie.

"This protest is not about stopping the project. I would characterize the relations between the DeLamberts and the company as friendly and cordial. He has an opportunity to talk, but we are not sure they have listened. The lawyers are not as cooperative," McKeachnie, a former lieutenant governor and a prominent Vernal oil and gas attorney, told Jones at a September hearing.

Company officials deny their operations are causing the DeLamberts' water woes and have done the hydrological studies to back that up.

"We don't want to interfere with the rights of anyone. We want to prove we can do bitumen extraction in an environmentally friendly manner. It wouldn't be environmentally friendly if we didn't pay attention to our neighbors. We are concerned but we feel we are not impeding any of their water rights with our wells," said Doug Thornton, the company's regulatory manager.

The ranchers have steadfastly refused to align themselves with the anti-fossil-fuels activists who have targeted the mine with blockades and encampments, hoping to thwart what they say is the dirtiest of dirty energy projects.

Unlike conventional oil production, tar sands requires strip mining and intensive processing of the ore. But US Oil Sands executives say their proprietary method of extraction avoids the environmental pitfalls associated with most tar sands operations, which rely on heated water to separate the hydrocarbons. Instead their method uses citrus-based solvents and water that is recovered and reused, they claim, while the spent ore will be clean enough for use in sandboxes.

DeLambert has long tolerated oil wells on his land, including a messy well that hasn't yielded much in years and whose operator has resisted plugging. But that problem is nothing compared with dry springs, which could put the ranch out of business.

DeLambert suspects that the core sampling may be to blame. The company bored 180 holes into the mesa to measure the thickness and quality of the bitumen deposits. DeLambert wonders if those holes are allowing precipitation to pass through the asphalt layer and slide away without reaching the aquifer feeding his spring.

University of Utah geology professor William Johnson, who has extensively studied this area's hydrology, doubts the core holes could have played such a role, but he does agree the mine company's activities may pose a threat to the DeLambert ranch. His published research has documented a hydrological connection between the bitumen mine and the springs feeding Main Canyon.

In 2011, US Oil Sands began drilling in search of water, but kept coming up dry. It finally struck water on the rim of Main Canyon after going to a depth of 2,600 feet. Last summer, the company pulled 50 acre feet of water for use on road projects.

Around then the DeLamberts' main spring went completely dry for the first time, according to their lawyer. The company argues that its well could not be the cause because it taps an aquifer 700 feet below the spring.

Johnson says the data don't exist to prove whether or not the wells are to blame.

"It could be reducing the pressure so the springs don't flow as much," Johnson said. "On the other hand, we are in a prolonged drought. You really should be monitoring not just the springs in Main, but also in other places where there is no possibility of a connection."

DeLambert agrees drought could play a role, but noted springs in nearby canyons remain wet.

Ultimately the state engineer, who was sympathetic to the DeLamberts' predicament, found nothing to indicate US Oil Sands wells have dewatered the Main Canyon springs. Jones OK'd the water transfer, but required the company to contract with the federal Bureau of Reclamation for the use of this water, which is a portion of the massive right associated with Flaming Gorge Reservoir.

McKeachnie acknowledged his clients lack the hard data to prove US Oil Sands is purloining their water, but they can cite the legal doctrine of "res ipsa loquitur" — Latin for "the injury speaks for itself."

"The water that used to come to his springs has disappeared and we haven't been able to determine where it has gone. The only thing that has changed is the work on top of the mountain," McKeachnie said. "If we were a big company and had hundreds of thousands of dollars, we might be able to find where the DeLamberts' water has gone. We don't have that. All of the information is either undeveloped or in the possession of the company."

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713. Twitter: @BrianMaffly