This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

As the temperature dipped below freezing Tuesday, Mindy Vincent locked her Ford Escape and trudged down Rio Grande, her arms overflowing with supplies.

She flashed a welcoming smile to the groups of people huddled together on the sidewalk, her bright red sweatshirt standing out against the night.

"How was your day?" she said to no one in particular. "Need clean [syringes]?"

Vincent's questions were met with wary stares. Until a red-headed woman, her thin frame hunched over against the cold, broke the silence.

"They're free?" asked the woman, about 30.

"Absolutely!" Vincent exclaimed, her hands already red and chapped from the cold.

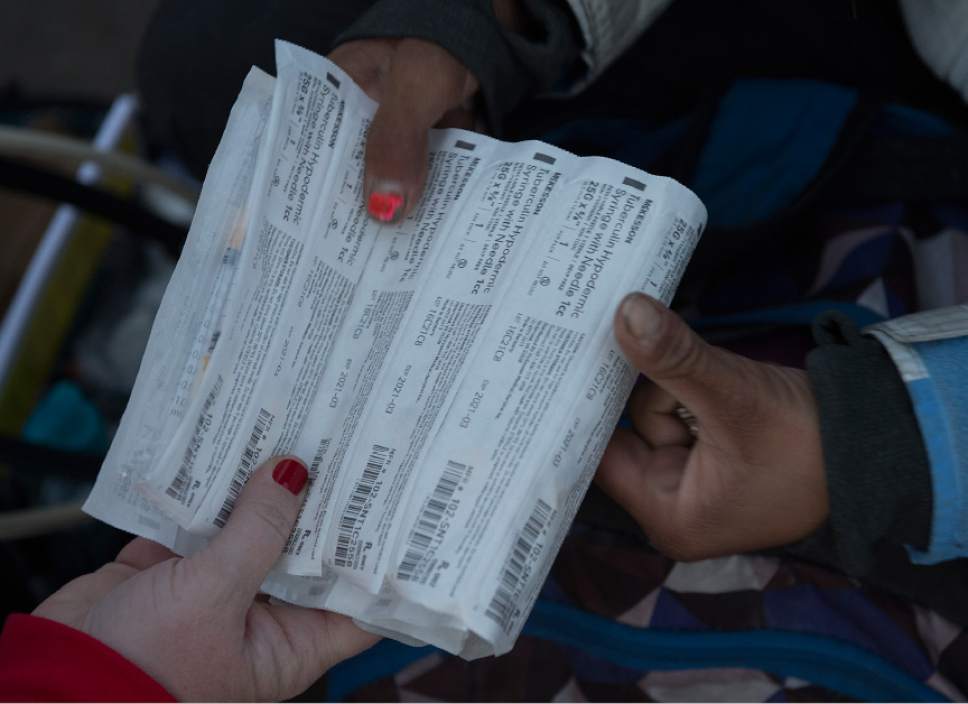

Tuesday was only Vincent's second day handing out clean syringes as part of the state's new syringe-exchange program, but she already had a system: Sign people up — with little identifying information — dispose of their dirty syringes and hand them a bag of supplies that includes clean needles, condoms and cotton balls.

Vincent was thrilled when lawmakers this year passed a measure establishing the program, adding the state to the list of 34 others that already had syringe-exchange programs.

So thrilled, in fact, that she quit her job at First Step House so she would have more time to dedicate to the cause.

This summer, she started Life Changes Counseling — a small Heber City center specializing in addiction therapy — giving her flexibility to run the Utah Harm Reduction Coalition.

She founded the coalition to focus on operating the syringe-exchange program, as well as provide education, services and advocacy.

"It's about helping people right where they're at," Vincent said.

Studies have shown that these programs can help curb the risk of infections, such as HIV, and experts say they help connect intravenous drug users to services when they are ready to quit.

Exchange programs "provide people with that point of contact so when they are ready for treatment, they can access it more easily, and [the programs] do, in the long run, reduce HIV and hepatitis C transmission," said Heather Bush, the Utah Department of Health's viral hepatitis and syringe-exchange coordinator.

It's a situation Vincent understands all too well: she was a meth addict until nearly 10 years ago, losing custody of her son several times while bouncing in and out of the criminal justice system.

And as she handed out supplies Tuesday, she shared those experiences with people uncertain of her intentions.

"How did you know to bring all this stuff?" a man asked Vincent as she dumped 30 syringes into a brown paper bag.

"I was a drug addict," she said. "But 17 years was long enough."

The state's syringe-exchange law requires the department to enroll agencies that participate in the program. As of last week, only Vincent's two agencies — the counseling center and the coalition — had enrolled since early November.

The problem, largely, is funding. Lawmakers established the program without allocating any money toward it. That means anyone who wants to operate one has to generate the funds to support it.

Once Vincent's coalition receives nonprofit status, she will start accepting donations. But until then, she's dumping her own money — more than $5,000 so far — into the cause.

Because of that, the coalition will be doing mobile outreach only a few times a week.

But she said she hopes to have a storefront in the downtown area sometime next year.

"This is such a need," Vincent said. "I know I'm fighting the good fight."

And the people crowding around her on Rio Grande, lining up to get new syringes, were evidence of that.

"You guys are awesome," shouted a blond woman buried under a pile of blankets, her brown bag of syringes clutched tightly in her hands. "Thank you."

Twitter: @alexdstuckey