This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Owings Mills, Md. • He looked at the ceiling and imagined a fantasy deep into the future: He'd be rich then, and the name Steve Smith would be famous.

No more solitary, two-hour rides on the No. 7 bus to his school in Los Angeles, no more nights spent staring at the bottom of his brother's bunk, no more brown carpeting and wood paneling in the room Smith's aunt had opened to them. Smith liked to dream, and he'd spend hours tossing a football at the ceiling and twisting his hands to catch it from different angles.

One day the aunt walked in and asked why he did it. The greats, he told her, never stopped: someday, he said, he'd make it to the NFL.

She listened, nonetheless telling the teenager to consider more realistic goals. This crushed Smith. He had allowed her into the private recesses of his world; now, at least in his mind, she'd responded with doubt.

In two decades since, he has never spoken to her again.

Kinder, not gentler

Steve Smith is trying to be nice. Really trying, and this isn't easy for him. In fact, he kind of hates it.

"I don't care about your feelings," the 37-year-old wide receiver is saying, sitting in an office at the Ravens' practice facility. "I don't care how you feel. I don't care about what you like or dislike." Pause: "I'm just being honest," he says.

This is mellow Steve, older-and-wiser Steve, more introspective and less guarded Steve. In the old days, he might not be sitting here. He said no to interviews so often reporters would rat him out to the league. He would disappear into an empty room during family gatherings so often his wife, Angie, would tell him he might be present but that didn't mean he was here. His kids once called him unapproachable.

But all that is in the past, and the truth is, Smith didn't like that part of himself. His inability to let anything slide was driving people away.

"I just really want to be myself, be nicer and be more approachable," Smith says. "Because honestly, that's how we're supposed to be."

Smith has spent a lifetime attempting to convince the world of something, and thought it has acknowledged his presence and perhaps his greatness, he does not have it in his nature to simply stop and enjoy the sunset.

This season he has more unnecessary roughness penalties than any other receiver and has feuded with two rookie cornerbacks, Cincinnati veteran Vontaze Burfict and a fan on Twitter who was complimenting Smith. Teammates sometimes call him "old man" just to watch him react.

"He'll laugh about it," Ravens receiver Kamar Aiken says. "But I know in the back of his head, he's pissed off."

And this is nice Steve, or perhaps more accurately: increasingly self-aware Steve. He knows now that these are the emotions that pushed him toward the NFL, that made him a star, that have him on the verge of the hall of fame.

Something to prove

Two years after the Panthers drafted him, Smith hired a sports psychologist, attempting to untangle his emotional wiring.

Years earlier, a friend in Los Angeles had shared one of Smith's secrets, so after that he stopped confiding in most people. When reporters wrote about Smith's anger, he attempted to prove them wrong, often by confronting them. He stocked away names and years and circumstances, a mental filing cabinet of slights, and nearly obsessed over who had disrespected him.

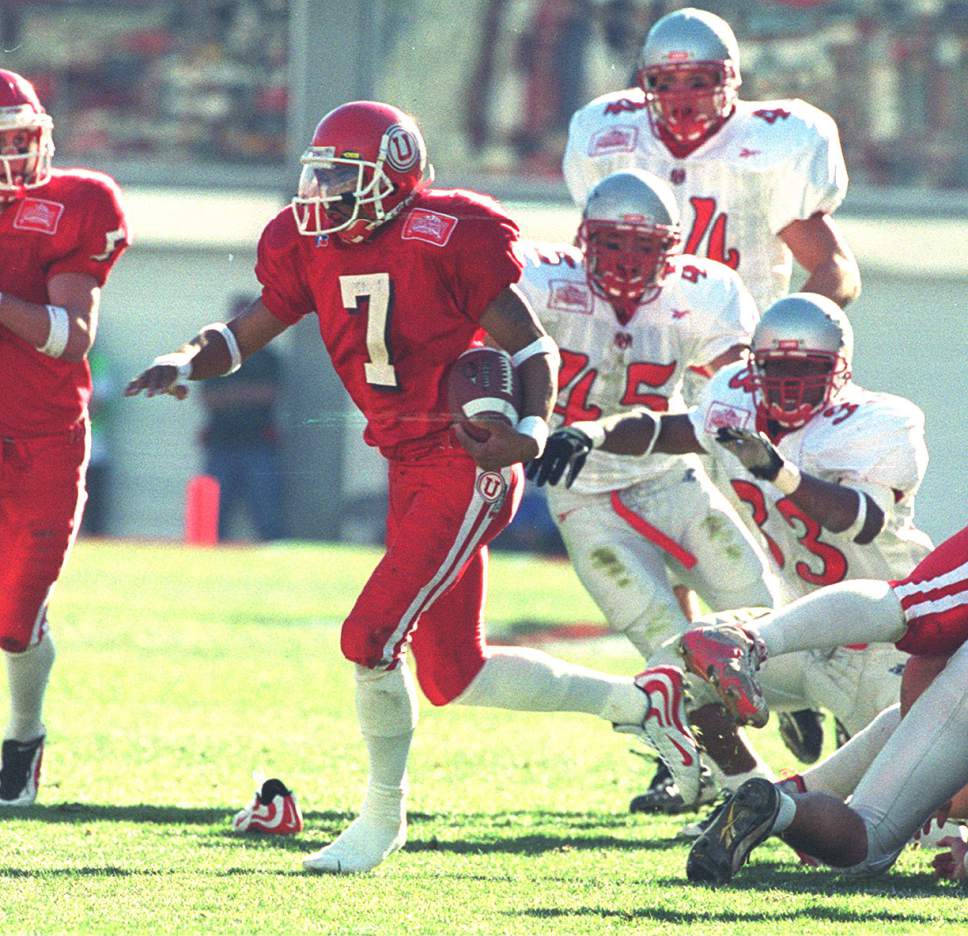

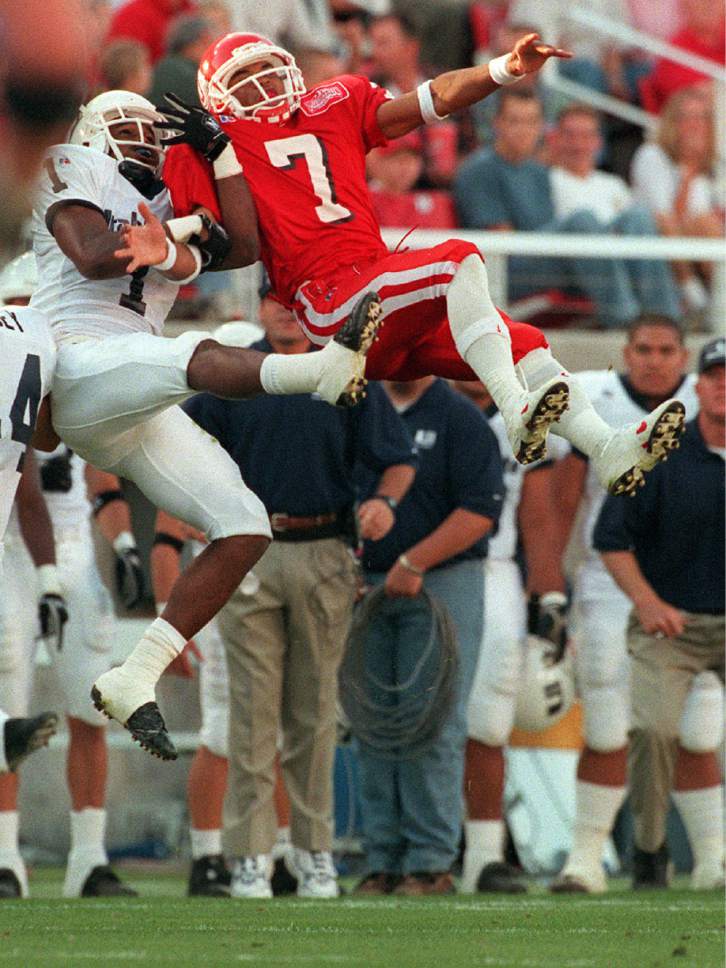

Next to the negative articles in his mind was the folder of doubters. There was the coach at Notre Dame who, after Smith wrote to him pledging his desire to play for the Fighting Irish, responded to inform him the school didn't accept junior-college transfers. The critics before the 2001 NFL draft who said a 5-foot-9 slot receiver had limited viability in a big-man's league. The Carolina executives who, when he was seen as an injury-prone rookie out of Utah, attempted to pay him below the going rate for third-round picks — before he stormed into the general manager's office and told him these negotiating tactics weren't going to fly.

"What's your deal?" Smith says former Panthers GM Marty Hurney asked him once, and the receiver made a list of things that could answer Hurney's question and went to his office to read it.

So Smith hired the psychologist, and because he liked lists and mental notes so much, the counselor encouraged him to start an actual folder. He filed away the Notre Dame letter, along with the pre-draft report Smith can still recite nearly word-for-word: "very quick, runs decisive routes," he says. "But kind of slow in and out of his breaks; durability is a factor."

He started a list of goals and stuffed them into the binder: daily, long-term and "dream" accomplishments: Do these things, and the chorus will be proved wrong.

By 2003, he was talented and driven, generous and thoughtful, volatile — he broke a teammate's nose at age 23, and another at 28 — and complex. He was gregarious sometimes, moody others, perfectly happy to be alone as he once was on the bus in Los Angeles.

He was perhaps one thing more than anything else: ambitious. Among his longer-term goals after the 2002 season was to reach a second Pro Bowl, be identified as a team leader, catch at least 85 percent of the "catchable" passes thrown his way. He wanted to buy his in-laws a house, become a franchise player, and be voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Gradually he began striking through the goals with black ink, catching 91 percent of his passes while helping Carolina to the Super Bowl following the 2003 season. Then a second Pro Bowl in 2005 (followed by three more since), the house for the in-laws, then in 2008 being voted by fans as the greatest player in Panthers history, then becoming the team's career receiving leader.

"This is the game," he says, "where you get to defy the odds."

The Panthers released him in 2014, and Smith signed with Baltimore. He announced last year he would retire after the 2015 season but ruptured his Achilles tendon; a month later, he decided he was again coming back.

Occasionally during his rehab he would pull out the letter from Notre Dame or the pre-draft report to read it, to feel the slights again. Or, for a different sensation, he'd open the binder and look at the dusty list of goals.

All but one had been crossed out.

Canton in his eys

He's smiling now, talking about the Hall of Fame. Fifteen years ago, he was a hothead kick returner; now, Canton is in sight.

So many years ago, it was the first line on the young dreamer's list. Now it's the only one left. But he is not a lock for induction, and Smith knows this — and because this is what he does, Smith has constructed an emotional barrier in case he falls short.

"It's not so important," he says, "that I'll die if it doesn't happen."

He goes on talking about how he doesn't need football anyway (he has not revealed his plans about his playing future, though he says he has decided). About how it is preposterous that he is being nicer and more accessible these days because anger might've brought him to the doorstep of Canton, but affability could be what carries him over the threshold.

"I'm not intentionally trying to be nicer to people so they'll vote for me," he says. "I've been so rough with people because I've been so burned and hurt, and the way I grew up — but I don't live in that atmosphere anymore. And I have to let ... that ... go."

No, he keeps saying, the Hall of Fame doesn't matter. And, because this is Smith, it doesn't in the same way he insists no one's opinion can bother him, that he doesn't think about how he'll be remembered, that he doesn't care when a rookie cornerback claims he doesn't respect Smith or a teammate jokingly calls him "old man."

It doesn't matter, because admitting how much it does matter would leave him vulnerable. And Smith decided long ago, after young Steve's aunt came into that room with brown carpet and told him to think more responsibly, that he could never allow himself to be vulnerable.

And so he goes on talking about how little the Hall of Fame matters to him. He's leaning forward now. The smile is gone.

"Here's the reason why it won't: Whether I get there or not," he says, "I'm playing with house money. I'm blessed, man. I'm a knucklehead from L.A. who didn't have ... nothing. And look at me now."

Occasionally his aunt reaches out to him. Smith ignores her, has for years, will continue to. He opened himself up to her, she hurt him, and in Smith's mind there is no greater sin.

He is nicer now, more mature and wise. If nothing else, he knows himself and his flaws — and, he says, his limitations.

"I know what I'm capable of," he says, "and what I'm not. I'm not going to be something with her I know I can't be."

He goes on.

"I don't like that about myself," he says. "But that's part of who I am."