This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

William Hamilton used to get irritated when people flashed him photos of their grandchildren. Then his daughter gave birth to triplets eight months ago — and now, he's a showoff, too.

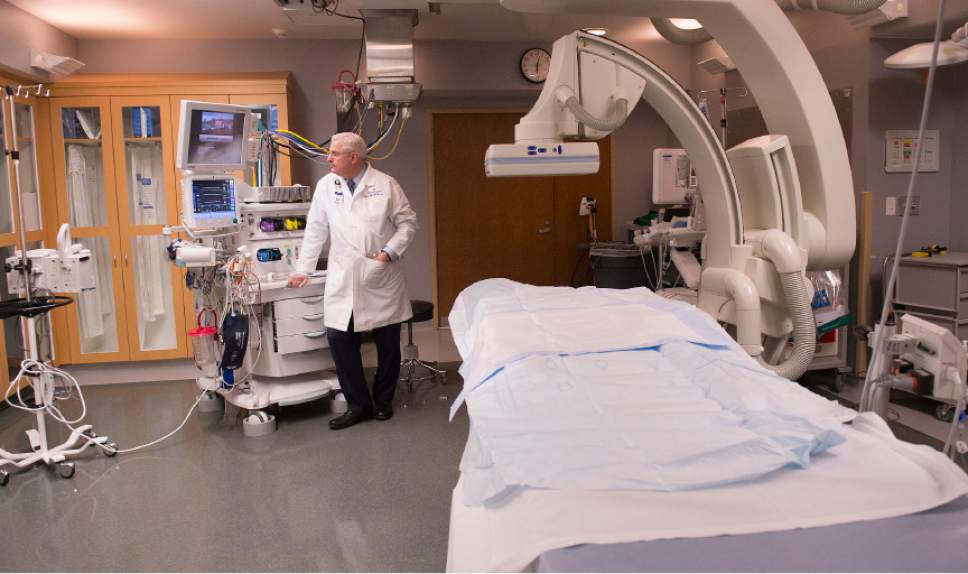

"I can see why they do it now," said Hamilton, a longtime anesthesiologist at Intermountain Medical Center. "But mine really are cute."

Spending more time with his three newest grandkids is just one reason Hamilton, 64, is looking forward to retiring next year.

Physicians of the baby-boom generation, like Hamilton, are preparing for retirement more than ever. In 2015, 18 percent of Utah physicians reported plans of retiring within five years, compared to 9 percent in 2010, according to the 2016 Utah Medical Education Council's report on the state's physician workforce.

"There's more to life than working every day," said Hamilton, who's spent the last 32 years with Intermountain. "I still have a bucket list of things I want to do."

But as more physicians retire from the medical profession, the trend is worsening an ongoing doctor shortage in Utah, experts say. With 207.5 physicians per 100,000 population, the state ranks 43rd in the nation, according to 2015 American Association of Medical Colleges data.

"Our concern is having an aging-out population of physicians when we can't afford to have less people treating the population," said Michelle McOmber, CEO at the Utah Medical Association.

McOmber said the shortage is being compounded by problems at the other end of the pipeline: too few residency slots for graduating Utah medical students, rising costs of higher education and lower physician pay compared to other states.

The council's report, based on a 2015 survey, examines statewide physician demographic and practice information. It also recommends ways to improve health care access across Utah, such as introducing medicine as a career choice early and supporting physician recruitment and retention efforts.

In 2015, the average age of Utah physicians was 53 years old, the report states. More than half of them were between the ages of 45 and 64 in 2015, compared to 44 percent in 2010, according to the data.

At the University of Utah, "we're aging dramatically," said Wayne Samuelson, the U.'s vice dean of education. "Physicians are aging and retiring at a rate faster than we can train them."

Intermountain Healthcare and St. Mark's Hospital say their physicians, too, are aging and there is a growing need for physicians.

Officials with the three systems say top-notch medical students are graduating from the U., currently the state's only medical school, but that there simply aren't enough. The U. accepts 125 medical students each year.

U. officials are asking state lawmakers this year for $50 million to help build three new facilities — an ambulatory care center, a rehabilitation hospital and a medical education facility — to replace University Hospital.

The U. project's total cost is estimated at about $420 million, with other funds to be drawn from operating revenue bonds and private donors, including private foundation in California.

Though the project won't boost the number of medical graduates in Utah, a second medical school, Rocky Vista University, will enroll its first class of 125 students this summer. Classes begin in July at the university, a 107,000 square-foot facility in Ivins.

The for-profit, Colorado-based osteopathic medical school will focus on primary care — a desperate need particularly in rural Utah, said Tom Told, dean and chief academic officer of Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Told grew up in Utah and said he saw the lack of access to health care in the southern region of the state.

"When I got involved in establishing Rocky Vista in Colorado, we had a lot of Utah students come and it was clear the need was still there," Told said. "It seemed like a good opportunity for us to establish a site in southern Utah."

The council's report states that Rocky Vista students "may be prime candidates for recruitment into the state's medical workforce in the most needed areas."

Graduating more medical students from Utah schools should help ease the doctor crunch, McOmber said, but she is concerned that a shortage of post-graduate residency programs will become even worse.

Officials did not have an exact count of residency slots available in Utah. Rocky Vista officials said they still are arranging these slots for their students. But Samuelson said about 50 graduating medical students leave Utah yearly to complete their residencies elsewhere, a number of them because there aren't available openings in the state.

That, in turn, hurts efforts to keep graduates here as evidence suggests people who become familiar with the state are more likely to stay long term. Between 2003 and 2015, the council's report found, 54 percent of Utah's practicing physicians had completed a residency or fellowship here.

But McOmber said the medical profession faces challenges well-beyond a residency program shortage. Many students are opting out of medicine because they can make a similar amount of money, she said, and go through less schooling, in other professions.

This is partly due to vast amounts of debt many take on to complete their medical training: 12.8 percent of Utah physicians who graduated medical school in the last decade reported more than $300,000 in debt at the time of graduation, according to the council report. That's compared to only 1.2 percent who graduated 21 to 30 years ago.

Both the U. and St. Mark's offer debt relief as an recruiting incentive for new physicians. The amount of assistance offered by the U. depends on the department, Samuelson said. At St. Mark's Hospital, physicians can choose between a larger yearly salary, a starting bonus or debt assistance, said Eric Rose, vice president of physician recruitment for HCA's Mountain Division. HCA owns St. Mark's.

Intermountain, however, does not offer any debt assistance, said Mark Ott, chief medical officer for Intermountain Medical Center and the Central Region.

"There's no question that [debt] drives medical students to certain specialties over others but we don't specifically say we'll help you pay off your student loans," Ott said. "We've been able to recruit without it."

And that's remained true, Ott said, even though physicians in Utah earn less than their counterparts in other states.

Utah "is a great place to live and work, and the cost of living is lower" than many major cities, Ott said. "They might make lower salary wise, but most physicians say they are very happy with their income."

As of two years ago, the median annual income for Utah doctors — adjusted for hours worked — was $175,000 per year for primary care physicians and $221,000 for specialists, the medical council's report found. Nationally, the median compensation per year is $263,307 for primary care and $360,367 for specialists, the report states.

At St. Mark's, the pay gap sometimes causes trouble when recruiting doctors, Rose said.

"If a physician's primary job requirement is pay," he said, "Utah is not where they come."

Each doctor, of course, makes his or her own choices.

Hamilton, the retiring anesthesiologist, said he isn't too worried about leaving Intermountain in the hands of the next generation. Every time someone retires, he said, people fret about how to replace them. But a new crop of doctors comes along, often more talented than their predecessors, and life moves forward.

So, Hamilton will finish out his medical career next year. He'll take one last walk through the operating room, then start planning trips to Europe and time with those cute grandkids.

Twitter @alexdstuckey