This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah faces a host of environmental challenges in 2017, but state officials say they are making one their top priority: air quality.

The state may need new initiatives for reducing levels of small-particulate pollution, the culprit associated with Utah's wintertime inversion troubles. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is proposing to reclassify three Wasatch Front counties — Salt Lake, Utah and Cache — as "serious" nonattainment areas, requiring stepped-up measures for cutting particulate emissions.

If the EPA proposal, which is up for public comment through Jan. 17, is approved, Utah will have to submit to federal authorities a new plan for limiting pollution before the end of the year.

While the federal Clean Air Act mandates Utah's compliance — with threat of penalties for noncompliance — staving off sanctions isn't the sole factor elevating clean air on the state's priority list, according to Alan Matheson, executive director of the Utah Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

"The priority is making sure that we continue to reduce our emissions, and ensure that we've got air that's supporting our health, economy and quality of life," Matheson said. "We all know people who struggle when the air is poor, and addressing that challenge is far more motivation than legal penalties."

Bryce Bird, director of the DEQ's Division of Air Quality, said the new air-quality plan — called the state implementation plan — is underway. So far, he said, officials have improved the air-quality computer models that help show how new regulations might affect Utah's air.

"We actually upgraded our whole modeling system," Bird said. "We're very confident that the model is better than what we had before."

Those models indicate that Utah County and Cache County are set to meet federal air-quality standards by 2019, assuming that emissions in those areas continue their downward trends.

But Bird said Salt Lake City will likely need additional emissions rules in order to meet the next EPA deadline. And it's not yet clear, he said, what those new regulations might look like.

State officials intend to study nonattainment areas across the country for strategies that might work here, he said, and then present the ideas for public input.

One possibility: requirements or incentives for Utah workplaces to reduce their workers' commuting trips.

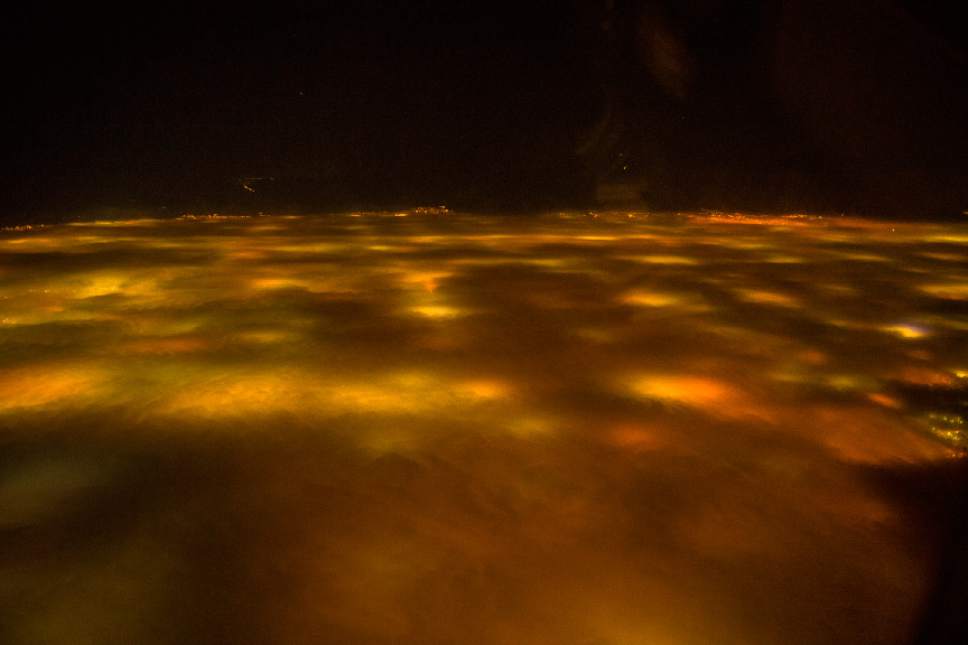

Such programs would call on large employers to help their employees get to work without being the only occupants in their vehicles during winter inversions, the Wasatch Front weather patterns that make Utah especially prone to accumulating unhealthy concentrations of particulate pollution.

Employers, Bird said, might consider organizing car pools, offering incentives for use of public transportation or allowing workers to telecommute.

"To be effective," he said, "it would need enforcement or reporting, too. And that's something we'd be discussing — how to quantify benefits and make [employer-based trip reduction] a permanent part of how we do business."

Bird's division hosted a symposium on employer-based trip reduction on Wednesday in hopes of kicking off the conversation.

Matt Pacenza, executive director of the environmental advocacy group HEAL Utah, said his organization plans to push for better enforcement of existing state air-quality rules this year.

For example, Pacenza said, Utah residents who live in the Wasatch Front nonattainment areas are already barred from burning solid fuels such as wood when the weather forecast calls for "mandatory action."

But, he said, the state doesn't have the resources to enforce that ban, and penalties are rarely applied. Likewise, the state has put in place myriad rules on emissions from businesses such as restaurants, dry cleaners and auto body shops. But again, he said, actual enforcement is sparse.

"The state is upfront about the lack of enforcement there," Pacenza said. "It's not a robust system of going door to door and making sure all these businesses have done what they are now required to do."

HEAL also intends to call for more monitoring of industry emissions; improvements to public transportation; renewal of state tax credits for zero-emission electric vehicles; and building codes that will make new Utah homes more energy efficient.

Ted Wilson, executive director of the nonprofit Utah Clean Air Partnership, or UCAIR, predicted that as more Utahns buy vehicles that comply with new federal emissions standards, the state's air-quality conversation will shift from transportation issues and instead focus on smaller, daily consumer choices.

"The bigger part of it in the future if we can get our cars cleaned up is going to be all the little things we do every day — what the experts call area sources," he said.

Educational campaigns may begin to shift away from encouraging residents to take public transportation and avoid idling their cars to suggestions on switching to stick deodorant instead of spray-on products, or choosing water-based paints for their homes.

Air quality is also likely to become more of a year-round topic in 2017, as opposed to something that comes up mostly in winter.

The EPA is expected to determine this year whether to adopt state proposals to designate three new nonattainment areas in Utah that exceed federal standards for ozone. That health-threatening substance, formed in the atmosphere when sunlight reacts with other pollutants, is usually a summertime concern.

Wasatch Front communities exceed ozone standards during the summer, according to state regulators. However, state pollution monitors indicate that Duchesne and Uintah counties have wintertime ozone spikes exceeding federal air-quality standards.

The state and others are researching ozone levels in Duchesne and Uintah counties to better understand the phenomenon.

Twitter: @EmaPen